CHAPTER V

NARA—THE HEART OF OLD JAPAN

A Japanese proverb says, "Never use the word ' magnificent' till you

have seen Nikko." They should have added, "Nor the word ' peaceful'

till you have been to Nara."

Nara is the very

heart of old Japan. The capital, which in ancient times was removed to

a new site on the death of each Mikado—but was always situated

somewhere in the provinces of Yamato, Yamashiro, or Settsu—came to its

first permanent stop at Nara in A.D. 709, and Nara continued to be the

seat of Government until the Court was moved to Kyoto in 784. At that

time, we are told, the city was ten times larger than at present. But

though it is nearly twelve hundred years since Nara's glory departed,

the passing centuries have been pitiful and gentle. They have cherished

the city's environs and the monuments embosomed in them, instead of

harming them, and have clothed them with the sweet, serene beauty of

honourable old age. For miles around Nara is beset with the ghosts of a

thousand years ago—ghosts as thickly cloaked with history as they are

overgrown with moss and lichens.

As one leaves

the railway station (the very name of such a thing sounds almost like

sacrilege here) the eye is arrested by a beautiful pagoda standing on

an eminence in the grounds of Kobukuji temple. It completely dominates

the landscape with its tiers of dark-grey roofs standing out in

contrast to the cedar-clad mountains beyond it.

NARA, THE HEART OF OLD JAPAN

The pagoda overlooks a pond called Sarasawa-no-iké, about

which

there is, of course, a legend. What would be the good of a pond in

Japan without one? The very idea is absurd! There was once a beauteous

maiden, who, though beloved by all the gentlemen of the Court, rejected

all their offers, as she had eyes for the Mikado alone. For a time she

found favour in his sight, but "the heart of man is fickle as the

April weather," as the Japanese say, and the Mikado's heart was after

all but a mortal one, though it pulsed with the blood of gods. He

neglected his beautiful plaything, until she, unable to endure his

indifference longer, stole out of the palace one night and drowned

herself in the garden lake. Her spirit still haunts its shores on dark

nights, and you can hear her sighs as the breezes play softly in the

trembling osiers round her grave.

There are many

famous temples at Nara, but it is Kasuga-no-miya, one of the most

beautiful old Shinto shrines in Japan, which draws many thousands of

pilgrims here annually. Kasuga lies deep in the heart of a magnificent

old park. To reach it one must go through the great vermilion torii, which forms

the park gate, and proceed for well-nigh a mile along a gravelled

avenue of lofty cryptomeria-trees. As soon as rikisha

wheels are heard, deer come bounding out of the bracken and turfy

shades from every side, to beg with great, soft, appealing eyes for a

few of the barley-cakes that comely little country musumés

sell at stalls along the wayside. Long immunity from molestation has

made the gentle creatures very friendly, and they will nibble from

one's hand, or even thrust their noses deep into one's pockets,

searching for some tasty morsel.

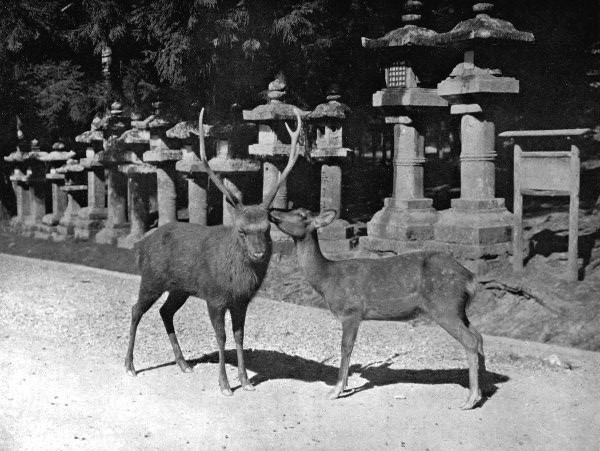

Deer are so

common in many of our own parks—Bushey and Richmond, for instance, and,

nearer still to the heart of the metropolis, Greenwich Park—that they

seem only in proper keeping with the English ideas of such places; but

an exceedingly charming and purely Japanese feature of this avenue is

the great number of old stone lanterns among the trees. They are votive

offerings to the temple from wealthy followers of the faith—many of

them the gifts of Daimyos—and their numbers are not to be summed in

dozens, nor yet by scores nor hundreds; in thousands alone can their

aggregate be found. In places they stand so close together as almost to

touch each other, and in ranks of many rows. These ishi-doro,

thickly spotted with moss and lichens, are the most decorative

ornaments that can be imagined, with the sunlight filtering through the

branches overhead and making soft harmonies of light and shade about

them. But their virtue as dispellers of gloom is far outweighed, as is

intended, by their fine artistic effect. They are not designed for

service, except on very special occasions, and are only lighted for the

yearly festival, or when some wealthy visitor makes a substantial

donation for the purpose; even then it can scarcely be possible to

light them all.

Never having been at Nara on

the occasion of its annual matsuri,

the 17th December, I have not seen the lanterns lighted; and, as I do

not come under the second category named above, I have modestly

refrained from gratifying my curiosity, hoping that some Croesus would

arrive during my stay and that he would graciously permit me to share

the pleasures of the reward of his munificence. King Midas did not

appear, though—much to my regret. I found, however, that several

dozens of the lanterns were lighted each night beside the main gates of

the temple when the weather was fair. Small saucers of oil, with

floating wicks, were placed in them, and when the wicks were lighted

and the little wooden frames—covered with rice-paper to shield the

flame—were in place, each lantern shed a beautifully soft glimmer all

around it.

The atmosphere of peace and

restfulness that encompasses Nara comes to a focus at the temple of

Kasuga. It is the peace of many centuries. In a.d. 767 the temple was

founded and dedicated to Kamatari, the ancestor of the Fujiwara family,

which rose to be the most illustrious in Japan. The picturesqueness of

the temple buildings themselves, and the beauty of their surroundings,

make a deeper, more touching appeal, however, than their mere

association with this great name. The lofty cryptomerias rear their

heads highest here, and among the brown shades of their mossy,

gravelled aisles great splashes of white and vivid colour are painted

into the picture with grand effect. These are the gateways and

pavilions of the temple, finished in snowy white and vermilion.

Massive roofs of thatch, a yard thick, cover all the buildings, and

every colonnade, gallery, and courtyard is kept as fresh and clean as

ever it was a thousand years ago.

It is said that

all the temple buildings are demolished, and rebuilt exactly as before,

every twenty years—like the temples of the Shinto Mecca,

Isé—and

that this rule has been adhered to ever since their foundation. They

are, therefore, incomparably more beautiful now than they ever could

have been in the zenith of Nara's history; for though Time is not

allowed to touch them, he has slowly worked marvels in their

surroundings, and, with the assistance of his handmaid Nature, has

enveloped them with an atmosphere of repose and beauty indescribable.

One cannot help but feel that this is hallowed ground; the very air is

heavy with the odour of sanctity.

Giant wistaria

vines have crept to the very utmost branches of the trees, and in May

the tall cedars themselves seem to burst forth into clusters of

drooping purple blooms. Through many an opening in the glorious arches

overhead the sun throws long shafts of light, which touch the pendent

blossoms, and then, glancing downwards, melt moss and gravel into

golden pools, or, searching out some spot on the brilliant lacquer,

make it glow with ruddy fire as the great orb himself glows at daybreak.

The deer roam undisturbed about the mossy, lanterned avenues of this

fairyland, and form lovely pictures as they stand framed in the burning

lines of some vermilion gateway. Fearing no rebuffs, they even wander

into the temple courtyards to be petted by the little daughters of the

priests, whose duty it is to go through the stately measures of the

ancient religious dance, kagura,

whenever called upon. The priests are born, live out their lives, die,

and are buried in the heavily-scented shade of the towering

cryptomeria-trees, and their children succeed them to live and die here

also.

Kasuga's numerous galleries and

colonnades

are hung with innumerable lanterns of carved and fretted brass and

bronze. There are at least as many round its courtyards as there are ishi-doro

in the gravelled avenues, and every gentle zephyr sets them swinging.

When these are all alight the gaily-coloured temple must be a very

fairy palace of beauty.

Pilgrims are ever

haunting the temple precincts. With slow step, and eyes bright with

happiness, they softly tread the avenues, kneel before every shrine,

and rest at every stall to feed the deer that nose around them. With

staff, broad-brimmed hat, and tinkling bell, they come to Nara from the

uttermost parts of Japan, just as they flock to Fuji and every place of

holy fame throughout the land.

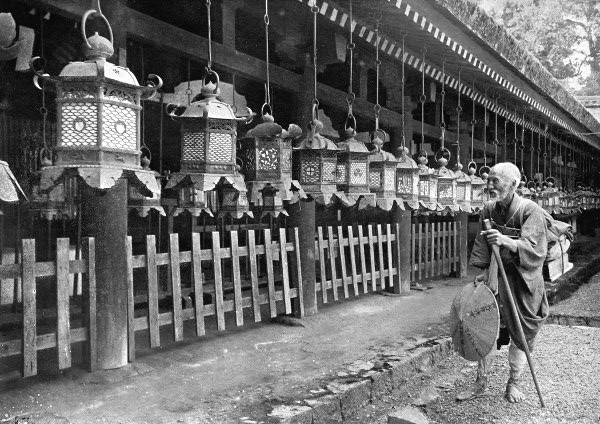

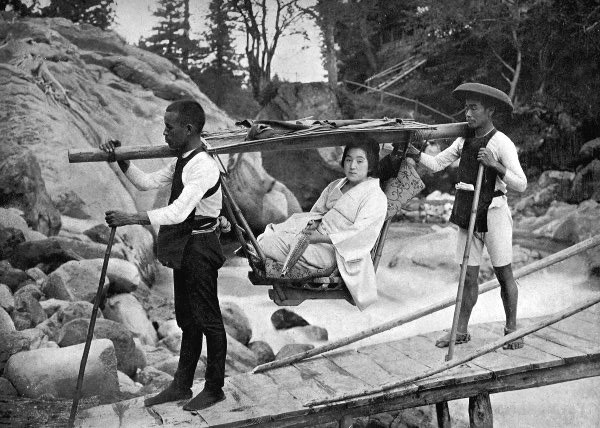

ON A PILGRIMAGE TO NARA

They come alone, and they come in bands; but to one and all the visit

is the climax to a lifetime of longing. When it is remembered that

these are members of some pilgrim's club, and that when the lot fell to

them to make the mission they believed in their hearts that they had

received a special call from the gods to visit them, it is easy to

explain the beatitude written on their faces and the light of happiness

in their eyes.

Such a pilgrim is the old man in

the picture. "Years bow his back, a staff supports his tread," yet he

had come on foot nearly two hundred miles to this holy place. Poor and

simple though he was, he was kind and gentle of speech, and, like his

fellows all the country over, courteous and respectful in every action.

His staff and broad hat of kaia

grass proclaim his mission. His kit he carries on his back, and his

kindly, smiling face is a faithful index to the contented, honest,

gentle soul within. At each shrine he visits he receives from the

priests some little token, and the temple stamp is impressed upon some

portion of his raiment. His needs are few and of the simplest, and his

daily expenses, all told, aggregate but a few pence. His progress is

slow, and perhaps he may be many months upon the road before he reaches

home again. But what of that? He is a type of the Old Japan, and in

the days gone by the time spent on a pilgrimage, as on the production

of a work of art, was never considered.

In a

pavilion of the Todaiji temple hangs the Great Bell of Nara, *1 and

Todaiji is also the home of the Nara Daibutsu—a prodigious image of

Buddha, the largest in Japan, though not to be compared with that at

Kamakura as a work of art. This image dates from 749 A.D., and was

completed, under the supervision of a priest named Gyōgi, in eight

castings, which are brazed together. The head, however, was melted off

during a

conflagration, and the present one was made to replace it towards the

end of the sixteenth century.

The great edifice containing the image was rebuilt about the year 1700,

but two centuries of exposure have told badly on it, and it already

looks somewhat shaky. In this respect it differs from any of the other

Nara temples. One of the great pillars which support the roof has a

hole in its base, and those who are able to crawl through this hole are

regarded with much favour by the deity. The task is not an easy one,

and if the divine favour be sought it is well to repair here in early

youth. One thinks of the camel and the needle's eye when estimating a

fat man's chances of accomplishing the feat.

Colossal figures of the Deva kings stand in niches at the principal

gateway, and every pilgrim as he passes chews a sheet of rice-paper to

pulp and tests his favour with the gods. He spits or throws it at one

of the figures, and if it sticks it augurs well for the fulfilment of

the desire.

Ni-gwatsu-dō, the Hall of the Second

Moon, is another Buddhist temple, very picturesquely situated on the

side of a hill, to which it clings by means of a scaffolding of piles.

Its whole front is hung with metal lanterns, and huge ishi-doro

stand in the grounds below. Fine old stone stairways, flanked with more

lanterns, lead up to its balconies, where the pilgrims pause to admire

the panorama over the park, and the beauty of the Yamato mountain

barrier which shuts out the view of the sea but twenty miles away.

There are other temples and beautiful sights far too numerous to detail

here. Only a bulky volume could do duty to the manifold charms of Nara.

1) Its dimensions are given in the chapter on "Kyoto Temples," page 9.

MY

DEAR!

A Study at Nara.

CHAPTER VI

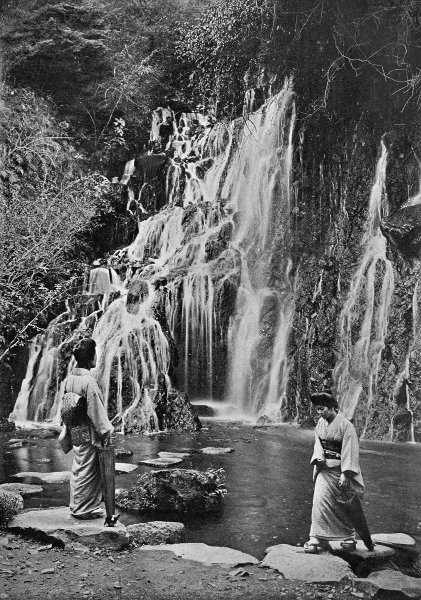

THE RAPIDS OF THE KATSURA-GAWA

One lovely April morning when all the land was sweet and smiling—for

Nature had donned the very fairest of her dresses and decked herself

with cherry-blossoms—two friends and I started for the Katsura-gawa.

Though I had shot the rapids several times, I never tired of this

beautiful river and the excitement of racing through its cataracts. The

brawling narrows and peaceful reaches, with their rocky gorges and

forest-clad hills, had always some fresh beauty and some new secret to

reveal.

From Hozu, the starting-point, to

Arashiyama, at the foot of the rapids, is a distance of about thirteen

miles, which is usually accomplished in an hour and a half if there is

a fair river running. When the water rises above a certain mark at Hozu

nothing will tempt the boatmen to essay the journey. On the other hand,

if the river be too low much of the excitement of the trip is missing.

If one chooses a day, however, when the water is just below the

danger-point, even the most adventurous spirits will not complain of

lack of excitement.

At the time I mention the

river was about normal—neither high nor low—and when we reached Hozu

we found the boat ready, and in charge of my favourite sendo,

Naojiro, one of the finest boatmen in Japan—a splendid athletic

fellow, lithe and active as a panther, whose honest, sunburnt face was

always wreathed in smiles.

The boat was

flat-bottomed, about thirty feet long, six feet wide, and a yard deep,

with three thwarts to brace its straight sides. These Japanese

river-boats are very flexible and frail-looking, but their staunchness

is remarkable. They only draw two inches when empty, and about four

when half a dozen people are on board, and when going over rough water

the flat bottom yields and bends to the waves, until it seems the

planks must surely open up and the craft be swamped. The boatmen say

the only way to make them stand the strain is to construct them of

these pliant planks; if built rigid they would speedily be buffeted to

pieces by the constant bumping on the water.

Our

crew consisted of four men, besides Naojiro, two of whom rowed with

short sculls on the starboard side, and one on the port, whilst the

fourth steered with a long yulo

at the stern.

For the first mile the river is wide and the current slow; as we

pushed out into mid-stream in bright sunshine, which was almost

insufferably warm for the time of year, the limpid water was too

tempting to be resisted. A simultaneous and overpowering desire seized

upon us. We looked at the water and then at each other. There was no

need for words. The wish was parent to the act. Bidding the boatmen go

easy, we quickly had our clothes off, and plunged into the clear green

depths, through which every pebble on the bottom was visible. For half

a mile we swam beside the boat, till swirling eddies began to appear

upon the surface of the water, and the banks rushed past us as they

closed in and steepened and the river narrowed for the first rapid. We

would fain have swum this first rapid, as it is an easy one, but the

men declared they would be unable to stop the impetus of the boat after

passing it, and we should be carried down the second race, which was

too rough to attempt to swim. We had, therefore, reluctantly to get on

board again—a feat which we found anything but easy to accomplish, and

almost impossible without a helping hand, at the rate we were being

borne along.

One of the men now took up his

position in the bow, with a long bamboo pole to ward the craft from any

danger that might threaten; and the rowers rested on their oars as the

boat slipped down the race with only an occasional touch of the

helmsman's yulo

to guide it.

The gentle, smiling stream on whose placid bosom we had started now

became a thing of moods. It danced and gurgled with glee; then for a

few brief moments it shrank back into itself, as if startled at its own

audacity, and, hugging the overhanging rocks, became Nature's

looking-glass, and mirrored snowy clouds, and beetling crags, and

woodland foliage in its depths. It was but the transitory humour of a

moment. The mood quickly changed again, and the troubled waters grew

restless and ill at ease, and, lashing themselves into a passion,

hissed with indignation and dashed fretfully and testily in impotent

rage against the rocks. Then they calmed once more and purred with

pleasure, and the sun beat down with scorching power into the stilly

glen, and the scenery grew weirdly beautiful—like that of old Chinese

paintings.

But a distant murmur marked the

approach of another change of mood. The murmur became a growl, and then

an angry roar of fury, as the stream took the boat into its arms and

drew it along with irresistible power. It was Fudo-no-taki, the

"God-of-Wisdom Fall," that we were approaching, one of the finest and

fiercest of all the rapids—a long, narrow incline, about eight yards

wide and a hundred yards in length, down which the river, gathering all

its waters together, shoots with terrific force.

Naojiro now took the bow position, and, at his word, the rowers shipped

their oars, and the helmsman, with a dip of his yulo, sent the boat

straight for the curling vortex that rolled over the brink of the

torrent.

In a twinkling we were dashing and bumping down the steep slope at

lightning speed, the thin, pliant bottom of the boat rising and falling

in undulations from stem to stern as it beat upon the waves. At the end

of this huge chute there is a level reach, and the falling water, as it

meets it, is tossed in a great wave high into the air. Over this the

boat leapt, with the impulse it had gained, all quivering and trembling

like a living thing, and well drenching us all with spray as the prow

dug deep into the foam. But with a bound the supple craft had shaken

itself free, and we were drifting easily along, through glorious

scenery, with pine and maple forests to the mountain-tops.

After a series of lesser rapids we came to Koya-no-taki, the "Hut

Fall," with a great boulder in the middle of a horse-shoe curve, and a

drop of a clear five feet where the water sweeps over a submerged shelf

of rock.

The now maddened river seethed and

roared in frenzy, and no other sound could be heard for the thunder of

its waters. Straight towards certain doom we seemed to fly, but the

captain never glanced behind him. He knew his men too well. Each was

ready at his post, with pole poised in hand, and each knew the spot for

which to aim. In another moment it seemed we must inevitably be dashed

to pieces as the boulder raced towards us, but, just as the crash was

coming, Naojiro's pole flew out into a tiny hole in the slippery

boulder's side. Simultaneously three other poles darted out as well.

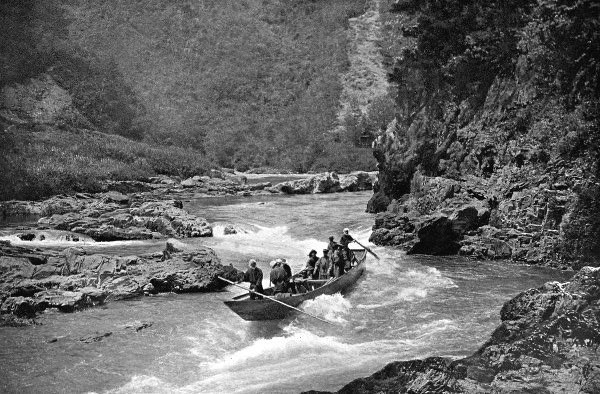

SHOOTING THE RAPIDS OF THE KATSURA-GAWA

There was a jerk, a momentary vision

of four figures putting forth their utmost strength and bending with

all their might against the rock, and I saw the swirling green water

rise level with the starboard gunwale, as for an instant our speed was

checked, and the boiling current banked up against the boat. But it was

only for a moment. The helmsman swung the stern round, and the great

ungainly craft, grazing the boulder as it did so, took the curve and

sprang over the deafening waterfall like some enormous fish.

It is truly grand to watch these splendid fellows dodging these

death-traps. A second's hesitation at a place like this and the boat

would be broadside to the stream and overturned; or beyond control,

and dashed against some rock with tremendous force—and the strongest

swimmer's skill could avail him little in this roaring torrent.

All down the river a keen observer may notice little holes in the rocks

at critical places, just large enough to admit the top of a bamboo

pole. These are not made by hand, but, incredible as it may seem, are

worn by the poles themselves, by centuries of use in log rafting and

taking merchandise down the river. They bear silent testimony to the

necessity of gauging the distance to an inch in order to navigate a

difficult place in safety.

Rapid after rapid

followed in quick succession—Takase-no-taki, the "High Rapid," in the

midst of lovely scenery; Shishi-no-kuchi-no-taki, the "Lion's-Mouth

Fall"; and Nerito, named after the famous whirlpool at the entrance to

the Inland Sea. Nerito is the most spectacular of all. It is a short

rapid, but has two difficult curves with rocky walls between which the

water sweeps with a roar at tremendous speed.

Our

boat hesitated for an instant on the rounded lip of green water at the

top of the fall, and then plunged for the precipitous wall on the left

at such a rate that this time it seemed no power could save us. But

Naojiro's clever hand was ready, and his eye was focussed on a certain

spot. Out shot his bamboo pole at the psychological moment straight

into a little crevice, and throwing his weight on to the pole, he

sheered the bow from the rock, and the boat went sweeping past the

precipice, to be caught into the vortex again so easily that, unless we

had been watching him closely, the masterly way in which he had avoided

disaster would have passed unnoticed.

The work

these boatmen do so gracefully and skilfully is by no means as easy as

it looks. What difficult feat does not seem easy to the uninitiated

when performed by an expert? Naojiro told me that he dared not let his

attention wander for a second in such places, as if he slipped, or

missed his mark, a serious disaster would certainly follow.

Several times we passed boats being towed upstream, closely hugging the

bank, with the trackers straining at the tow-ropes just as Hokusai

painted them a hundred years ago. Again, some lonely fisherman standing

on a jutting rock, with his straw coat thrown about him to protect him

from the sun, and a broad hat of reeds on his head—looking more like

part of the landscape than a living human being—was another Hokusai

study. Not unless one has seen these quaint figures of rustic Japan in

the flesh, can one realise how true to life was the work of the old

master whom Europeans most delight to honour.

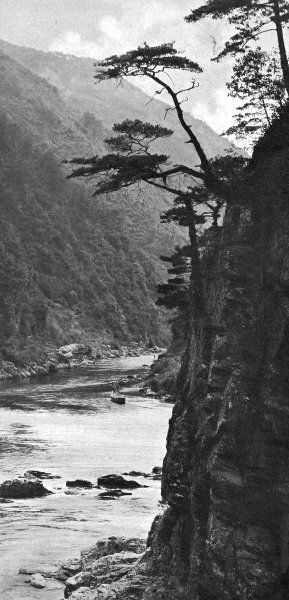

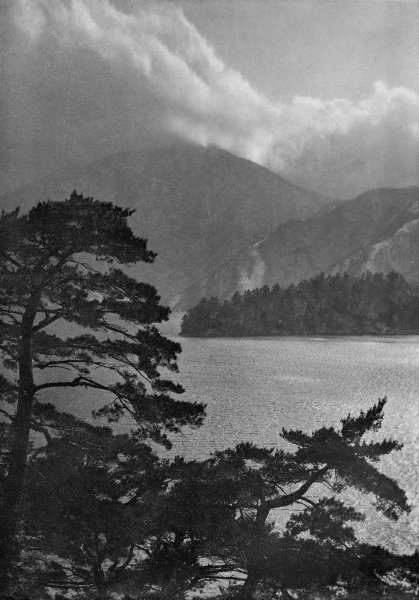

The

scenery grew more beautiful still as we neared the journey's end. Among

the forests on the mountainsides cherry-trees in blossom were lovely

colour-spots everywhere, and as we neared the Kiyotaki's tributary

waters the cliffs became perpendicular and almost grand. A dozen times

we had to bid the boatmen stop, that we might study more leisurely the

paradise of beauty through which we were passing.

All up the craggy clifFs

that towered to heaven,

Green waved the murmuring pines on every side,

and

the Kiyotaki came bounding and dancing to the parent river between

lofty precipices—to which old bristling pine-trees clung

tenaciously—joined by a little wooden bridge, and the whole scene was

the veritable original of a Hiroshige drawing. Then we glided among

tiny islets, and the river, expanding wide, became peaceful and almost

still—as if the worn-out waters rested after the torments they had

suffered.

We seemed to be floating on some

mythical stream that flowed through Fields Elysian—where storms never

raged, and winter's blighting hand never robbed the forests of their

springtime beauty; and where the blessed might find rest and spend all

Eternity drifting under the fragrant pine-trees, or basking in the

sunshine by waters more beautiful and musical than the fairest streams

of Arcadia.

It was Arashiyama, beloved of poets

and painters during all the ages—one of the fairest spots in this land

that Nature adorned when in the kindest of her moods. The

mountain-side, which towered sky-high, was pink and green with cherry -

blossoms and pine and maple trees that strove to hide each other; and

in the emerald river great trout were sporting among the blossoms

reflected in its limpid depths. Red old firs leant over the water,

stooping to the mirror below them; and framed among the cherry-trees

were dainty tea-houses with broad verandahs, where lovers of the

beautiful come and sit all day and feast their eyes on the sumptuous

repast which Nature has provided.

In boats, yuloed lazily along

by old sendos

who had spent their lives upon the river, pleasure-parties, with faces

uplifted, were gazing in wonder and rapture at the sweet harmony of

pink and green above them. Other pleasure-seekers were rambling along

the avenued river-sides, and the twanging of samisens,

ringing across the water from the tea-houses, showed that some at least

of the Nature-worshippers were varying their aesthetic revels with the

society of the indispensable geisha.

At Saga, a village on the eastern bank, we paid oif our boatmen, and

never did we pay money more willingly for any excursion in Japan. Here

a row of restaurants faces the river, and a slender wooden bridge

crosses it. Saga's one street is a bazaar of shops for the sale of

walking-sticks and household ornaments made of cherry-wood, and

beautiful stones from the river. Stones of good shape, from celebrated

places, are much sought after by the Japanese, who esteem such natural

articles highly; for specimens resembling some well-known island, or

famous rock, high prices can be obtained. I have seen a stone, well

covered with a much-admired kind of moss, in a dealer's window in

Tokyo, for which a hundred yen

(ten pounds) was asked, and it was not more than a foot in length. At

Saga, however, beautiful specimens from the river may be purchased for

a few shillings, and one I bought there long figured as a thing of

beauty in my room, placed, after the Japanese fashion, in a shallow

bronze dish, with just sufficient water to cover the layer of river

gravel on which it reposed.

In the spring of 1906

I was invited by Mr. Hama-guchi of the Miyako Hotel, best and most

courteous of hotel managers in Kyoto, to accompany him and two other

guests—Mr. Adam, editor of the Japan Gazette,

and his brother—on a trip up the river. This is even more interesting

and exciting than the down-stream journey, for one has plenty of time

to admire the scenery; moreover, the races and rapids—which

the

boat slips down so

easily—present quite a different aspect as one is being towed slowly

and laboriously up them.

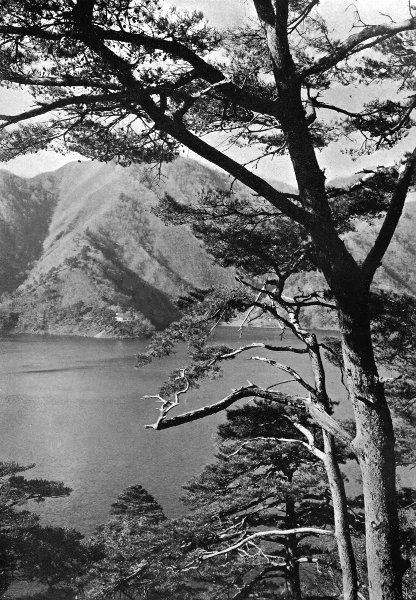

A GLEN ON THE KATSURA-GAWA

We had my favourite crew, with Naojiro at the bow, and one extra man to

tow, making six all told. No steersman was necessary, as the captain

kept the boat clear of the rocks with his bamboo pole. The towing-ropes

varied in length from seventy to a hundred feet, so that each man had

plenty of room to himself without interfering with the others.

It was May, and the azaleas, which covered many of the hill-sides, were

a lovely contrast to the deep green of the woods. In the depths of the

gorge the heat was scorching, and the trackers, stripped of everything

save straw sandals and loin-cloths, were like ivory carvings as their

sleek bodies shone in the sun. With the certainty of mountain-goats

they leapt from rock to rock; but, though they put forth all their

strength into the harness round their lusty chests, their clean-cut

limbs never bulged with knots of muscle.

At

almost every touch of Naojiro's pole, at difficult places, it fitted

into one of the little holes before referred to; and from time to

time, when some rocky precipice stood barrier before them, the trackers

hauled in the ropes and crossed in the boat to the opposite shore. At

one place they all took to the poles, with ourselves lending a hand to

help; but our united strength did not avail to keep the bow to the

stream, and the current, whirling the light craft round, swept it

broadside along like a match-box towards a great boulder in the centre

of the river.

Here the wonderful alertness of the

men was manifested in a thrilling manner. It was quite an unexpected

incident, due to the fact that the boat drew so much water, as,

including my camera-carrier, there were eleven people in it—an

altogether unprecedented number in taking a boat up the river. The

current swung us round so quickly, once the boat's head lost the

stream, that the peril was on us almost before we saw it. But Naojiro

saw, and gave a shout of warning, and in a twinkling all were on the

side where danger threatened. Every pole struck at once, and bent

almost to the breaking point as the men threw their weight and strength

against the boulder, round which the water rose high and boiled in

baffled fury. The danger was over in a moment. The impact was avoided,

and we swept past the great stone, and well clear of it, to safety;

but admiration filled us at the exhibition of resource and vigilance

these sterling fellows had shown. Indeed it would be impossible to

praise them too highly. Had wc struck, nothing could have prevented a

disaster, for the current there was a good twelve knots an hour or

more. We all got out, except the captain, and scrambled over the rocks

to the quiet water above this place; the boat, freed from our weight,

was then easily pulled up without more ado.

Then

came Koya-no-taki, where the five-foot waterfall bars the way. We all

declared it quite impossible that we could ever surmount it; but

Naojiro only smiled and called to his minions to haul in closer on the

lines. Bracing his feet against the starboard side and his pole against

the rock, and bending his supple body with all his strength of sinew to

the task, he gave a word of command to the trackers, who pulled

together with a will, lifting the prow up the watery wall as if some

unseen power below impelled it, and we slid slowly to the higher level,

scarcely shipping more than a bucket of water in doing so.

At Nerito the straining trackers went on all-fours, gripping the rocks

with hands and toes, and the torrent rose to the gunwale on either

side. It seemed a miracle that five men could pull so large and heavy a

boat up such a swirling flood; but inch by inch they did it, and when,

at length, we floated in the smooth green water at the top, and looked

back on the roaring tumult, the feat seemed more miraculous than ever.

Once I attempted the up-stream journey with a less skilful crew and a

smaller boat, for my favourites were engaged. At Koya-no-taki we met

disaster. As he gave the word of command to pull, the captain missed

his mark and sent the bow under the fall, nearly swamping us. At our

shouts the trackers dropped the ropes, and the boat, full to the

thwarts, was carried back with great force against a rock, which stove

the top planks in for ten feet on one side. Fortunately, this rapid is

a short one, and we drifted to shore in the reach below without further

harm.

The men who pilot tourists down,

however,

are all masters of their craft, and take pride in the fact that they

have never lost a visitor's life. They dare not risk the revenue they

get by this occupation, from both foreigners and Japanese, by

entrusting the boats to unskilful hands. The men I had engaged on the

day of this adventure were not master-hands, and told me so at the

outset; but they were the only men available, as I had come without

notice, and it was quite an unusual thing then for anyone to go up the

rapids. At that time (1906) the brothers Adam, Dr. Roby and Dr. Barr of

Kyoto, and myself were the only foreigners who had done it. It is a

grand excursion for those who like something more exciting than the

down-stream run. The up-river journey takes about five hours, and the

double trip, with an hour's rest at Hozu, fills a most exhilarating day.

The boatmen alone are well worth going to study. In these rugged

volcanic islands every river is a torrent, and the men who make a

living on them, and the fishermen around the coasts, are the class from

which Japan recruits her tars. For agility, resource, and skill in

their craft, I know no finer type of men in all the world. The Island

Empire of the East has little to fear so long as she can draw upon such

fine material for her Navy.

THE INDISPENSABLE GEISHA

CHAPTER VII

THE GREAT VOLCANOES, ASO-SAN AND ASAMA-YAMA

The Japanese archipelago is probably the most active centre of

seismological disturbance in the world; and little wonder, for the

islands bristle with volcanoes, and seethe with solfataras and

hot-springs. Few are the weeks I have spent in the capital without

experiencing at least one earthquake. I have even felt several in a

night, and tremors for several nights in succession. The moment a shake

begins, one's thoughts fly to subterranean fires, and thence, following

up the line of cogitation, to volcanoes.

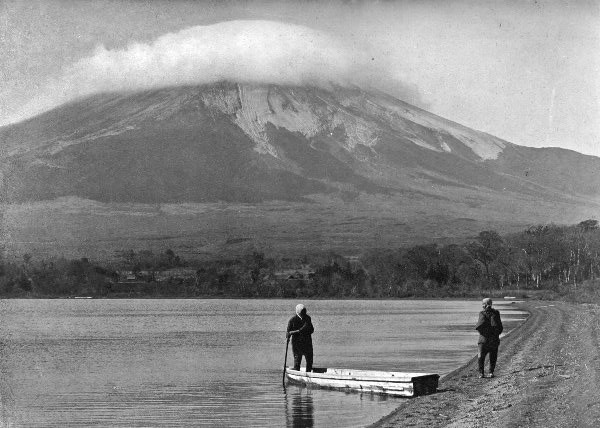

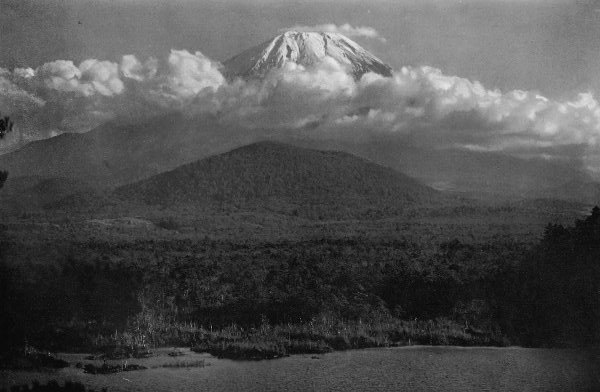

The two

finest active volcanoes in Japan are Aso-san and Asama-yama. Aso-san,

in the heart of the island of Kyushiu, is not only the largest active

volcano in Japan, but boasts the distinction that its outer crater is

the largest in the world. But Aso is too far from the beaten track for

most people and is very seldom visited, as its ascent entails an

eight-day journey, there and back, from Tokyo—though half this time

will suffice from the port of Nagasaki. Asama-yama, on the other hand,

can easily be ascended in a three-days' absence from the capital, and

being so accessible, as well as the highest active volcano in Japan, a

good many people find their way to the top each year.

The two volcanoes are totally different in shape and temperament, and

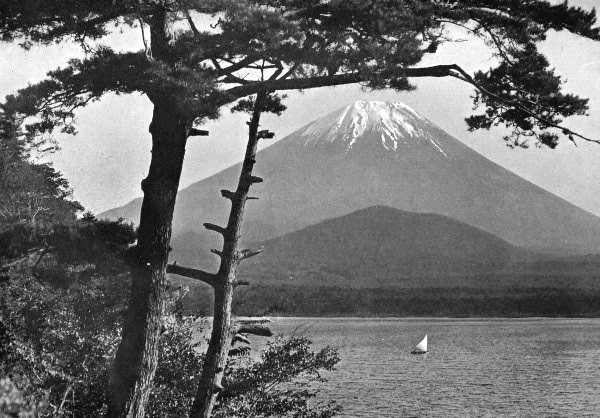

neither has any pretensions to the almost perfect outline of Fuji-san.

The peerless Fuji has the trim and comely form of youth, whereas Asama

is rounded with age, and Aso's colossal crater is nearly choked with

the accumulated ashes of untold centuries. Only a small fraction of

this volcano, once the greatest on earth, is now alive, yet even that

fraction is larger than any other crater in Japan. Aso is a

good-natured, even-tempered volcano, and it is not often that the

steady cloud of smoke and steam which it emits varies in volume; but

Asama is a fretful and irritable mountain, subject to violent outbursts

that are over in a moment. Sometimes Asama is restless for days

together, and explosions occur every few hours; then it calms itself

and is almost peaceful for many weeks before the angry mood returns

again.

One hot August night I started for

Kumamōtō, en

route

for Aso-san. Soon after leaving Nagasaki a thunderstorm broke, and

raged with truly tropical severity. For over an hour the lightning was

so incessant that the train was illuminated as though by daylight. In

one minute I counted over seventy flashes; this was about the average

of each minute for over an hour, and the noise of the train was

completely drowned in the ceaseless overlapping crashes of the

thunders. As we flew past hills, and valleys, and rice-fields in the

dead of night, every mile of that beautiful Kyushiu country was shown

to us by the flickering lightning as on a kinematograph; whilst a

deluge poured from the skies such as I have not seen equalled even by

the almost unparalleled rainstorms of Java. Then the flashes became

less frequent, and the scenery was revealed in a series of brilliant

pictures. A village would be at one moment a typical scene of night,

with only a light showing here and there. An instant later the lights

had gone, as if extinguished, and every house, and window, and bamboo

fence, stood out as clearly as if in sunlight. So the wonderful play of

day and night continued for a further hour, dispelling all thoughts of

sleep.

Early the next morning we arrived at the

historic old town of KumamotO, and, after settling our things at a

hotel, went out to see Suisenji park—one of the most celebrated

pleasure-gardens in Japan. The weather was almost unbearably hot—about

90° in the shade—but the park was at its very best. Gentle

little neisans

invited us to take tea as we entered the gates, but we ordered shaved

ice and fruit syrup instead, and lay on the turf in the shade to sip

it, whilst we revelled in the lovely summer scenes around us, and

rubbed our eyes lest we might be dreaming.

There

was a large but very shallow lake, with water clear as the crystal of

wisdom in the forehead of Buddha. It was studded with pretty islands,

covered with dwarf trees, old stone lanterns, and summer-houses; stone

and rustic bridges stretched over the water, and temples, torii,

crooked pines, and banana-trees were scattered about the garden

everywhere. A miniature artificial Fuji-san graced the opposite shore

of the lake, and beyond it the eternal smoke-wreaths of the great

volcano Aso mounted to the heavens. The scorching sun glinted on the

brown and azure wings of a thousand dragon-flies darting across the

water, and great carp glided about in shoals over the gravel and

water-plants in water not a dozen inches deep. The broiling August air

was all vibrating with the unceasing screams of cicadas, and tiny girls

and boys were paddling in the water or scampering over the

grass—innocent of a stitch of clothing—making the place echo with their

happy shouts of laughter. The whole scene was a very idyll of innocent

happiness and beauty.

At one end of this garden

of unalloyed joy the water deepens, and here a score of boys and adult

men were bathing and frolicking about the banks—as naked as the

children—whilst fair and dainty promenaders of all ages walked amongst

them unembarrassed, not even noticing the nudity around them. Such

Arcadian simplicity is quite refreshing after the West and its

over-nice ideas of modesty.

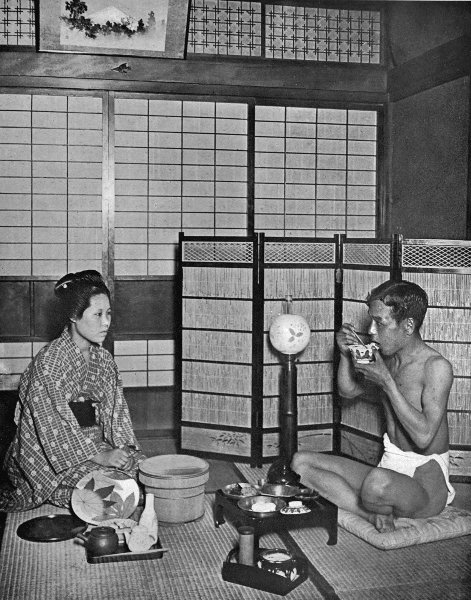

Negligée is de rigueur

at Kumamōtō in summertime, and when my Japanese companion sat down to

dinner that night his sole and only article of apparel consisted of a

loin-cloth. I seized the opportunity to record this interesting phase

of native custom by taking two flashlight photographs. This proceeding,

it seems, was the cause of much perturbation in Kumamōtō town the

following day. In order that the smoke from the flashlight might not

enter the house I had placed the camera, and fired the powder, on the

balcony immediately outside the open shoji

of the room in which this informal meal was taking place: a report

like a pistol-shot accompanied each of the brilliant flashes.

Now it so happened that the balcony faced a river, on the opposite bank

of which there lived a journalist; but we did not know about the

journalist at that time.

Early next morning we

found a number of people on the river banks, closely observing the

operations of some dozen men who were digging in the bed of the shallow

stream. We also watched for a time, wondering what it all meant, and on

enquiry learnt that they were searching for two meteorites which had

fallen at that spot the previous evening. They expressed much surprise

that we knew nothing about them. The journalist, it seems, has seen

them fall, and several other people who were with him had witnessed the

unusual phenomenon also. He was directing the digging operations, and

spared a tew moments to show us an article he had contributed to the

daily paper on the subject.

SUMMER NEGLIGEE AT KUMAMOTO

It

told how at nine o'clock the previous evening, as the writer was

sitting with a few friends on the verandah of his house, two

magnificent meteorites had fallen within a few minutes of each other,

with loud explosions and accompanied by a blinding glare of light, into

the river, just opposite his house. This information was followed by an

expatiation on meteors in general.

As my friend

finished reading the paragraph to me, and our eyes met, we both burst

out laughing, much to the annoyance of the journalist, who was hardly

flattered at this unexpected reception of his ''scoop." We then

explained to him how at that precise hour we had made two flashlight

photographs on the balcony of the hotel, and that it was, without

doubt, these flashes that he had taken for meteors. At this explanation

there was a shout of laughter from the assembled observers of the

digging operations, and the crestfallen journalist retired, much

mortified at the collapse of his theory and at the jokes of the crowd

at his expense.

After settling the affair of the meteors

we started, by basha,

on the twenty-mile journey to Toshita village, from which we were to

make the ascent of the great volcano. The road is a very fine one, well

drained and of excellent surface, and avenued with tall

cryptomeria-trees the greater part of the way. The scenery too, in

places, is magnificent. Nearing Toshita the road wound along the side

of a deep gorge, every inch of the steep bank of which was terraced

with wonderful skill for rice-fields. The air was filled with the

murmur of the tiny streams that fell everywhere from terrace to

terrace, until they finally leapt over the cliffs into the foaming

torrent a hundred yards below. The south bank of this stream—the

Shira-kawa, or "White River"—is a precipice several hundred feet in

height, above which thick forests clothe the mountains to their

summits. In every mile at least a dozen streams danced down the steep

slopes, adding to the hum that filled the air, and beautiful cascades

sprang from the beetling cliffs on the opposite shore to fall in clouds

of rainbowed mist into the rocky gorge.

The inn

at Toshita is a poor unpretentious place, close by the river, and one

goes to sleep lulled by the music of its waters.

We were up early the next morning to have a bathe in the public

hot-spring, where we found a number of villagers already tubbing. Much

curiosity was evinced as I entered the plunge, which is common to both

sexes, and many observations were made on my personal

appearance—especially by the ladies. My smattering of the language

enabled me to gather that these comments chiefly concerned the colour

of my skin, and it was with satisfaction I noted that they took a not

unfavourable tone.

At eight we started on foot

for the ten-mile walk to Aso's crater, with several coolies to carry my

apparatus and luggage, for we intended to traverse the mountain and

continue the journey across the entire island of Kyushiu.

It was a glorious day, but fearfully hot. At the village of Tochinoki,

which we passed through, there are many baths, fed by hot-springs,

where rounded youth and shrunken age of both sexes bathe together. Two

years later, when I again visited this place in March, I saw wrinkled

old fellows, whose skin was like a withered apple, lying sound asleep

in the water, with their heads resting on the steps, and with flat

stones placed on their bellies to keep their bodies submerged. They

spend the entire winter in the warm water thus, seldom, if ever,

donning their clothes. The water is said to be very efficacious for

rheumatism, but it seems to have evil properties as well as virtue, for

several of the bathers were piebald with pink and yellow patches.

Passing through the village we came to an open rolling moor, and the

great volcano loomed straight ahead of us. I wish those who believe

Japan to be "a land of birds without song," as one writer has falsely

described it, could see this moor in early spring-time. When I crossed

it again on my subsequent visit in March the very skies seemed to ring

with celestial music, and the air trembled with the melody of a myriad

unseen larks singing at the gates of heaven. I have never heard

anything like this birdland concert in any part of the British Isles,

or any other land. Every few seconds a tiny speck would appear far up

in the blue, and the sweet piping notes and trills of one little voice

of the chorus grew clearer and clearer as the tiny owner fluttered

down, down, down—at times hovering almost still in the air—till the

singer was lost to view in the grass. But still the little throat

pulsed and throbbed out the lay of love, as the happy little creature

wooed its mate upon the nest. Only the happiness of love could inspire

such rapturous melody as this.

That was a day

never to be forgotten. A perfect spring morning on the hills! Not even

Switzerland can eclipse the mountains and moors of Kyushiu for a tramp

on a bright spring morning, when the very air seems charged with the

history, romance, and mystery of Old Japan, and pulsates with the

twittering and trilling of a thousand larks. But in August it was a

different matter. The heat was getting terrific as we went along at a

good gait over the soft springy turf, with the serrated edge of the

great ash-hills, which encircle the inner crater, far above us and

beckoning us on. This moor is inside the ancient crater, and the

mountains all round us marked the lip of the outer rim, which is

fourteen miles from brim to brim.

The geysers of

Yu-no-tani now appeared ahead, sending great billows of snowy steam

high into the heavens—making a beautiful contrast to the azure of the

sky, the yellow of the sunburnt grass, and the deep green of the

forests which surround the springs. At a distance of two miles we could

hear the geysers hissing, but as we drew nearer the sound became

rapidly louder, and changed from hissing to rumbling, and then to a

deep booming that made the ear-drums tingle. Finally it grew into a

deafening roar that shook the earth, as we stood beside the fissures

from which the steam shrieked at terrific pressure. There is power

enough going to waste there to run all the factories in Kyushiu, if it

were harnessed. From the force with which the steam was emitted it

seemed as though the rocks must momentarily be rent asunder, and this

is probably what would happen were it not that these, vents act as

safety-valves.

Miles of black ash-hills, which

reflected the 90°-in-the-shade heat into our faces with

scorching

power, now had to be traversed, and our clothing was soon as wet as

though we had been in a river. We should certainly have welcomed a dip

in one at that stage of the journey. We passed many farms and

rice-fields, for the ground is very rich, and wherever water can be

obtained abundant crops are grown. It is said there are over twenty

thousand people living in the villages within the outer crater walls.

When we reached the summit of the ash-hills which form the second lip,

we rested and restored our wasted tissues with lunch, whilst enjoying

the grand spectacle of the crater, only three miles away, pouring

volumes of smoke and steam into the cloudless skies. Fortified by food

and rest, we soon disposed of the remaining distance, passed the

temples at the foot of the cone, and were plodding up to the crater's

brink.

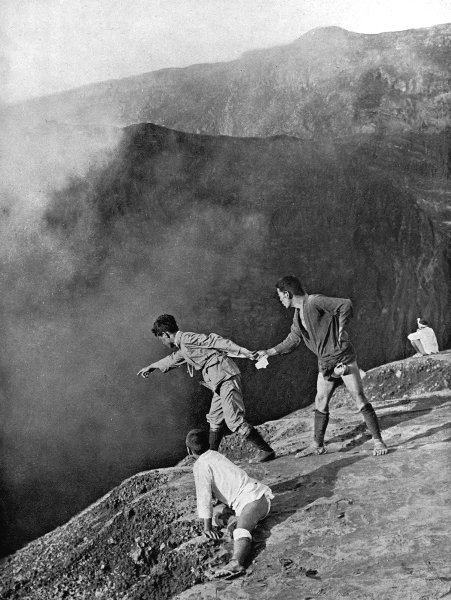

AT THE CRATER'S BRINK, ASO-SAN

It

behoved us to be very careful how we stepped, for the ash deposited is

of so soluble a nature that the recent storm had turned it into

slippery mud, and we had more than one fall and long slide in the mud

before reaching the edge. It is a most dangerous spot, as the bank dips

towards the edge in places, and a fall there might easily precipitate

one into the crater.

Aso's crater is a truly

direful place. The walls are not coloured like those of lava mountains,

but are black precipices of accumulated ashes, with only streaks, here

and there, of the more solid matter within them. Occasionally the

clouds of vapour that floated up from the great pit parted, and we

could see the crater bottom, with its thousand cracks and fissures,

from which the steam hissed and roared as at the Yu-no-tani geysers.

Once the wind veered for a few moments and we were quickly enveloped in

the steam, which sent us running, sliding, and tumbling to get away

from the suffocating fumes that gripped us in the throat and set up

paroxysms of coughing; yet I saw butterflies flying across the abyss

and emerging from the noxious vapours unharmed.

For the benefit of those of photographic predilections who read these

lines I would offer a few remarks about these fumes. I learnt much

about photographing volcanoes at Aso's crater, and the lesson was an

expensive one, as lessons taught by experience usually are. On my first

visit to the mountain I took with me a number of isochromatic, as well

as ordinary plates, in my dark-slides. All the isochromatic plates were

completely ruined by being exposed to the sulphurous fumes, which it

seems attacked the silver in the film. Never having used such plates on

a volcano before, I had no idea that anything wrong had happened, and

after descending the mountain I went on exposing these plates for the

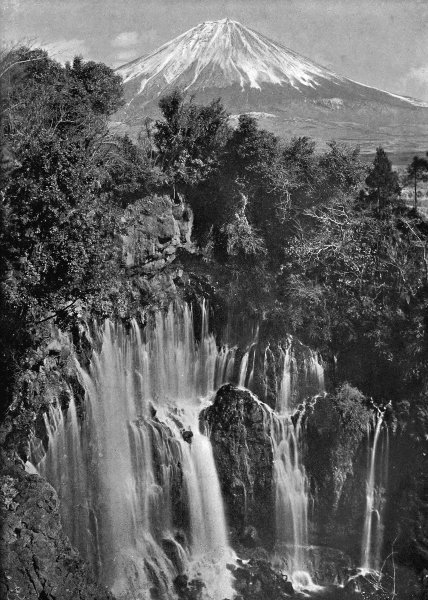

next two days on such fine subjects as the Chinda waterfall, and some

wonderful basaltic formations and other scenic views. Months later,

when I came to develop the plates in California, I was completely

nonplussed to account for the extraordinary manner in which the latent

image came out. The films were covered with blotches, and when the

negatives were dry, parts of them were positive. They were perfectly

useless, and it was only when I remembered that these plates had been

subjected to Aso-san's sulphurous vapours that I was able to account

for the occurrence. The ordinary plates, strange to say, were not

affected in any way whatever.

Those who know what

it means to make an expensive journey in order to secure photographic

results, and then to find that plates of splendid subjects—which one

may never have a chance of getting again—have been ruined by accident,

will understand my feelings when I realised what my thoughtlessness had

cost me. I therefore offer my experience as a warning to others never

to allow their plates to be exposed to the action of sulphurous fumes.

At the time of my visit there were two separate craters active within

the confines of the walls, and two inactive cones, but these are

matters that are liable to change every time the volcano has a fresh

outburst of any unusual nature. The highest point of Aso-san is

Taka-daké, or "Falcon's Peak,'' which is 5630 feet. There

are

several others nearly as high, and from the north side they give a

magnificently broken appearance to the mountain, which is quite

unsuspected from the west. From the town of Boju the five serrated

peaks of Aso-san, with the steam pouring skywards behind them, make no

little pretence to grandeur.

We stayed on the

mountain till long after the setting sun had turned the clouds of steam

to fiery flames; then, as the moon rose over the jagged peaks, and

shone with weird beauty through the ghostly vapours, we started on the

journey down to Miyaji.

Every hour of the rest of

the trip across Kyushiu was full of interest. The town of Takeda is

most picturesquely situated in a hollow, surrounded by high hills which

are pierced by over forty tunnels to render the town accessible. Only

by passing through several of these can it be entered. There are pretty

waterfalls near here, flowing over the tops of closely-packed, upright

basaltic columns, and the scenery all round the little town is

singularly beautiful.

Perhaps, however, Beppu and

Kanawa, at the end of the journey, were the most interesting places of

all. They are situated on the shore of the Bungo Channel, the

south-west entrance to the Inland Sea.

The whole

of this neighbourhood is so volcanic that hot-springs abound almost

everywhere. Beppu town is filled with public bath-houses; every

private house has its hot-spring, and the sea-shore is bubbling with

almost boiling water. The natives of the place throng to the beach in

hundreds—men, women, and children—and, scooping out a hollow in the

sand, they lie down in it and cover themselves up so that only their

heads are unburied. Thus they parboil themselves for hours, and even

sleep there. I tried this method, but found that the water which

percolated into the hole I dug was so hot that I could not stand in it,

let alone lie down in it.

At Kanawa, a village a

few miles away, the crust of the earth is so impregnated with volcanic

heat that almost anywhere steam can be tapped by punching a hole in the

ground with a crow-bar. Nearly every house has a set of holes outside

it, which are used for cooking purposes. These have to be plugged up,

when not in use, to keep the sulphurous steam from entering the

household.

Surely the most extraordinary baths in

Japan are to be seen here. After soaking in the public plunge, the

people crowd—a dozen or so at a time—into caves in which the heat is

terrific. In half-an-hour they creep out, covered with mud which has

fallen from the roof, and stand under jets of almost ice-cold water

which come from other subterranean sources. This arcadian Turkish bath

is said to be very efficacious for the cure of rheumatism.

There are many other baths at Kanawa, some of them arranged as long

troughs about fifteen inches deep and wide enough for a bather to lie

in at full length. In these the bathers recline side by side. There is

one trough for men and another for women, but it is quite common to see

old and young of both sexes soaking alongside each other and chatting

sociably together.

There are less pleasant places

at Kanawa also—one of them a boiling bog of deep green, sulphurous

slime, and another of brilliant green, boiling sulphur-water—which I

was told were favourite resorts of suicides. As I gazed into the

horrible sloughs I thought it would indeed require truly superhuman

courage, or madness, to impel the fatal plunge.

On one of my trips round Fuji-san I was fortunate enough to meet Mr.

Denis Hurley of the London War Office, who was possessed with the same

desire as I—to visit Asama. We therefore spent several weeks

travelling together, and then, one gloomy afternoon in October, headed

for Karuizawa—about six hours' journey by rail from Tokyo.

Asama is 8280 feet high, but as the village ot Karuizawa, the

starting-point for the ascent, is 3279 feet above sea-level, it leaves

only some 5000 feet to be climbed after leaving the train; and after

all it is a climb only in name, for this accommodating volcano has most

considerately spread itself in such a manner that it is merely a walk

of several hours up a steady incline to the top.

A PUBLIC BATH AT KANAWA

The railway from Tokyo follows the Nakasendo—the old mountain

highway

of Japan, which in feudal days connected the capital of the Mikado at

Kyoto with the Shogun's capital at Yedo—but there is no scenery of any

remarkable interest until the town of Myogi is reached. At this point

the line enters a mountain region of the most mystifying beauty. For

several miles, from here onwards, the much-painted Myogi-san on the

left is a wondrous conglomeration of overhanging cliffs, beetling

crags, and towering Gothic peaks which lean far out from the vertical,

seeming to menace everything below them with immediately impending

destruction. The whole mountain was clothed in a glorious autumn garb

of every shade of red and orange, blended with brown and green; and

spiky pine-trees pertinaciously clung to the most impossible of its

precipices, or bristled against the sky on the uttermost and most

inaccessible of its pinnacles.

At Yokugawa, a few

miles further on, the railway becomes of great interest to those of a

technical turn of mind. The steep gradient from here onwards—one in

fifteen—renders traction by an ordinary locomotive impossible, so a

steel rack is placed between the rails, into which cog-wheels in the

bed of the engine engage. This is the Abt system, similar to that used

on the Gornergrat and several others of the mountain railways of

Switzerland.

The engineers of the undertaking

were confronted with enormous difficulties at this point. In addition

to the height to be overcome, the country is so intensely rugged as to

necessitate the mining of no less than twenty-six tunnels, of an

aggregate length of something like three miles in a distance of seven.

Progress up the incline is naturally slow, not over eight miles an

hour, and as the volume of smoke emitted by the throbbing, straining

engine would be a source of great discomfort to passengers, the Swiss

method is also adopted for overcoming this inconvenience. The engine is

attached to the rear of the train and pushes it; and to prevent the

smoke being drawn by the draught through the tunnel ahead of the

train—as it inevitably would be—as soon as the engine enters each

tunnel a canvas curtain is drawn across the opening to shut off the

draught. The smoke is in this manner kept stationary until the engine

has emerged from the other end, when the curtain is drawn back again

and it is allowed to blow out.

In several places

only a few score feet separates one tunnel from the next. As we passed

these openings, fleeting glimpses could be caught of scenery,

exquisitely beautiful, where the lovely tints of autumn mingled with

the distorted shapes of the grim volcanic rocks; and, as the sunlight

waned, the jagged pinnacles and spires stood out in weird and

picturesque silhouettes against a lurid sky.

We

saw Asama, the object of our visit, for a few brief moments from the

train, a faint smoke issuing from the summit; but night had fallen ere

we reached our destination, cold and hungry, and, though the outline of

the mountain could plainly be seen in the darkened sky, we were too

intent on finding a warm room, a good meal, and a hot bath, to feel

much interest in it that night.

There were no

rikishas at the station, and when we had tramped the mile to the inn we

found the place shut up and apparently deserted, for few visitors go

there at that time of the year, and only after repeated efforts could

we succeed in making ourselves heard. When at length the door, with a

great clatter, was unbarred, we were welcomed with customary courtesy

and a chorus of greetings from the host and two little smiling maids.

They had hastily bundled out of the beds to which they had retired for

warmth, and, with much bowing of their glossy, black heads, apologised

for keeping us waiting outside on such a frigid night.

The warmth of the welcome, however, whilst cheering to the spirit, did

not help to raise the temperature of the hotel; and we went shivering

to our rooms, with maledictions on ourselves and on each other for

having been so foolish as to disregard the advice we had been given in

Tokyo—to telegraph ahead that we were coming. Braziers, however, were

quickly filled with glowing charcoal; hot tea was brought; warm baths

were prepared; and as the mercury in the thermometer on the wall went

up, so did our spirits; until at length, after a boiling hot tub, we

sat down to a hastily prepared but excellent meal, fully resuscitated

from our six hours' incarceration and fast in that chilly train.

There is nothing of any particular interest about Karuizawa itself,

though the high location and cool air make it a favourite resort for

residents of Tokyo during the hot summer months. It was the mountain,

however, that we had come to see, and at this season of the year we

were willing enough to give all the cool airs the place could boast for

a few hours of grateful sunshine. And fortune was more than kind, for

the morning after our arrival was clear and still—a lovely October day.

Nothing could be wished for more, so at 7 A.M. we started out with a

guide, and three coolies to carry our lunch and my heavy photographic

apparatus and plates, which weighed about 80 lbs.

There had been a keen frost overnight, and in the crisp air the volcano

stood out sharp in every detail, with a faint white vapour issuing from

its rounded top. Scarcely had we started when one of the coolies gave a

shout and pointed to the mountain. On looking in that direction we saw

a wonderful sight. A great ball of steam shot upwards from the crater

and floated like a monster balloon up to the sky. This was immediately

followed by clouds of dense, black smoke, mingled with great billows of

vapour, which poured forth in bellying convolutions, and piled upon

each other, higher and higher, until an immense column, ten thousand

feet or more in height, floated over the mountain. A high air current

then caught the top and flattened it out and tilted it, and finally the

whole column drifted off lazily southwards, staining the skies a

bluish-grey, as though a heavy rainstorm were approaching. I have never

seen a grander sight than that cyclopean pillar of writhing smoke and

vapour pouring up into the vault of heaven on that clear, sunny October

morning.

We had not bargained for such

marvellously good luck as this. To have a faultless day, and to find

that the volcano was in an unusually fierce state of activity, was

fortunate indeed, and well calculated to cheer the soul of any one bent

on securing photographic results. Our host of the hotel came running

after us, warning us to be very careful how we ascended the mountain,

and exhorting us not to venture near the crater unless smoke was

issuing freely. Reasons for this sage advice I will give later. We had,

however, made up our minds to see the crater, and intended to look into

it that day, be the risks what they might.

Leaving Karuizawa behind us, and passing through the quaint straggling

village of Kotsukake—the cottage roofs of which were covered with

stones to weight them down in the strong winds which prevail here—the

road led past rice-fields and sparkling streams with quaint

water-wheeled mills; thence on to a beautifully-wooded, sloping moor,

which soon changed to rolling hills of volcanic ash and scoriae,

overgrown with grotesque pines.

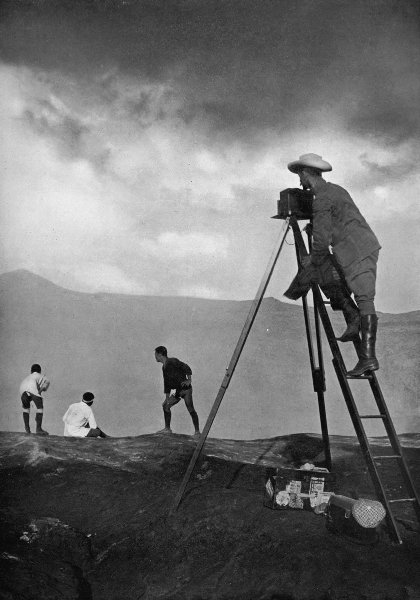

PHOTOGRAPHING AT THE CRATER'S LIP, ASO-SAN

The hillsides were golden in

the sun, and the silver-tipped kaia-grass,

which flecked the gold, made a foreground of feathery beauty for every

view. The frost had covered the trees and kaia with millions of minute

crystals, which sparkled like gems in the sunlight, and as we rapidly

covered mile after mile through the lovely woodland, and ascended

gradually higher and higher, the simple beauties of this undulating

country seemed as charming as more showy landscapes, the praises of

which have been sung by every writer on Japan.

The great

mountain mass lay straight ahead, but since the explosion at 7 a.m.

scarcely a trace of vapour had issued from the crater. At 10 a.m. we

passed round the side of Ko-Asama, or "Baby Asama "—a small extinct

volcano which lies at the base of its larger namesake, and whose slopes

were crimson with autumn tints. Shortly afterwards we reached the place

where those who come on horseback must leave their steeds behind and

proceed the rest of the way on foot, for, like all volcanoes in Japan,

Asama-yama is sacred, and above this spot no horse may tread. From here

to the summit it is simply a matter of walking over a bed of cinders

and pumice, which gets steeper and looser as one nears the top. Ash is

constantly ejected from the crater, and most of it falls on the upper

part of the mountain; the accumulation of centuries thus accounts for

the smooth, round appearance which the volcano presents when viewed

from a distance.

The lower slopes are overgrown with a

network of vines bearing small seedless grapes, from which the natives

make a kind of jam. At 11.20 a.m., as we were toiling up this incline,

another explosion occurred, and again vast clouds of smoke and steam

belched out from the crater and rose for thousands of feet into the

air. A muffled

roar, however, was the only sound which reached us at this distance. A

gentle breeze had by this time sprung up, causing the smoke to drift

off rapidly eastwards, and as it floated overhead a shower of ash fell

around us.

We relieved our coolies of the contents

of

the lunch basket shortly after this, for the guide told us that the

mountain was extremely dangerous when in that mood, and sometimes

ejected showers of stones; it would therefore be unwise to tarry long

enough at the summit to lunch there as we had proposed.

At I P.M. we reached the top of the

great ridge ot the outer cone. The

ground hereabouts was exceedingly soft from the quantity of fine ash

that is intermittently being deposited. It was studded with myriads of

stones, some of which bore silent testimony to the soundness of the

guide's warning, for they were quite warm, showing that they had been

ejected in the recent explosion. There was a slight depression beyond

this, and then another slope, which is the inner cone. The roar of the

great cauldron could be heard as we arrived at this spot, but when we

reached the summit a few minutes later, and stood on the crater's

brink, a truly marvellous spectacle lay before us.

We

saw an immense pit, six hundred feet or more across, and almost

perfectly round, with perpendicular walls towering up from the bottom,

five hundred feet or so below. These walls were burnt, and scorched,

and stained with fire to every colour of the spectrum, and from a

myriad cracks and crannies sulphurous jets of steam hissed out, each

contributing its quota to the filmy vapours that rose out of the abyss

from the fires of Tartarus below. Through the thin steam the entire

crater floor was visible. It was a huge solfatara, with numerous holes

from which molten matter was spurting, and red-hot lava pools which now

and then were licked by little tongues of flame.

The noise of the place was truly

infernal. There is no other sound on

earth that can be likened to the sticky, sputtering buzz of a volcano.

It is fearful to listen to—this vibrating, throbbing, pulsating din of

ceaseless, steady boiling. The thing seemed to be fermenting with

suppressed rage, and one half expected that any moment it would burst

open and loose the furies it could scarce restrain.

The

whole summit of the mountain was covered with stones, some of which

must have weighed a ton or more. Many of them had obviously been

ejected quite recently, for the marks they had made in the soft ash

were fresh, and some of the larger ones were still hot, having been

thrown out from the crater in the explosion that occurred during our

ascent. The fresh ash, which falls after each such outburst, speedily

covers the stones, so that it is easy to see which have been expelled

most recently. Our coolies emphatically drew our attention to the

freshly-fallen ones, intimating that it would be exceedingly hazardous

to tarry very long where we were. The intense interest of the place,

however, and the wonderful views to be had from the lofty

vantage-point, made us disregard their warnings; there was so much to

marvel at, and all around us a glorious panorama of mountain scenery as

far as the eye could reach.

Eastwards there were tiers

of rugged mountains ending with the craggy peaks of Myōgi-san, and

farther north the Nikko range. Northwards were the Kot-suke range, the

mountainous district of Kusatsu, and Shirane-san; whilst in the west

that inhospitable mass of great barren peaks, which the Rev. W. Weston

has called "the Japanese Alps," was a dream of light and shadow in the

afternoon sun. Southward there rose the great Kōshu barrier, above

which, and far beyond it, the lovely

snow-clad cone of Fuji towered high, and surpassed in the beauty of its

faultless symmetry every peak within the range of vision.

Whilst absorbed in the contemplation of

these beautiful surroundings,

and the wondrous red and purple colouring of an ancient broken crater

on the mountain's western side, the time sped swiftly on, and it was

not until 3 o'clock that we prepared to leave.

Our

coolies went on ahead, but Hurley and I stopped a few moments for a

last look at the crater, from which we found it hard to tear ourselves

away. As we stood on the brink of the diabolical abyss there was a

crash like a thunder-clap, and the earth seemed to split before us as

the bed of the crater parted asunder and burst upwards, throwing

thousands of tons of rock against the walls. For a moment or two the

noise was like the din of battle. Masses of rock were hurled against

the cliffs and shivered to fragments with reports like exploding

shells, and showers of stones, whistling past us, shot many hundreds of

feet into the air.

It all occurred so quickly that I

cannot recall all my sensations, but remember thinking that my last

moment had surely come. It seemed we must inevitably be struck by the

falling stones. My first impulse was to seek safety in flight; but

after running a few paces it occurred to me that the stones were just

as likely to hit me running as standing still. Hurley had also started

to run, but was evidently seized with the same conviction, for, without

a word, he stopped too, and we both waited for our fate. Just then the

smoke, which rose from the crater immediately after the explosion,

swept in a great cloud above us, so that we could not see the flying

stones, or form any idea where they were likely to fall.

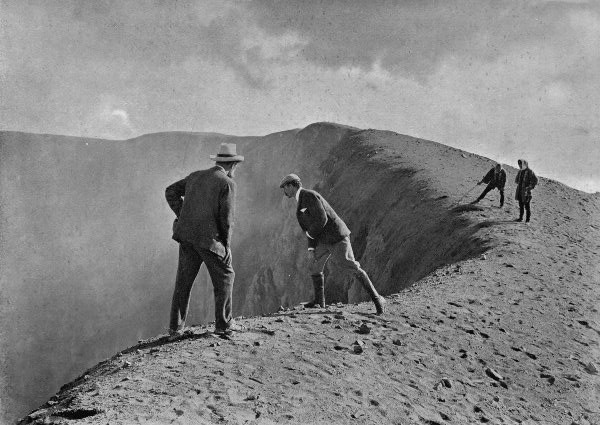

AT THE CRATER'S BRINK, ASAMA-YAMA

I shall not

soon forget those moments, as we gazed upwards, with arms involuntarily

held tightly over our heads for protection, waiting for

the descending missiles to drop out of the smoke-cloud and annihilate

us.

And then the stones came clattering

down—sticking,

with sharp thuds, deep into the ash. By good luck the main force of the

explosion was directed slightly to the east, and on that side of the

crater most of them fell. We were on the southern rim, and in our

vicinity only a sprinkling dropped compared with the hail of rock that

must have fallen a little farther off.

No sooner,

however, were we safely delivered from Scylla than the perils of

Charybdis were upon us. The smoke that was belching from the crater's

mouth now enveloped us, and in a moment we were choking and almost

asphyxiated with the sulphurous fumes. It was impossible to breathe,

as, with hands tightly pressed over our mouths and nostrils, we blindly

ran through the smoke for air. Fortune again was with us. In less than

twenty paces we emerged suddenly from the chaos into brilliant

sunlight, and staggered well out into safety before we fell upon the

ground, gasping and filling our lungs to their fullest extent with

great draughts of sweet pure air. It was a happy thing for us that the

strong breeze which was now blowing was coming from the south; thus

the smoke was blown away from our side across the crater. Had it been

blowing from the north we should have been unable to escape from the

suffocating fumes.

This column of smoke was a thing of

most awesome beauty, and held us fairly spell-bound. It belched up into

the air in great, black rolls, which were emitted with such force and

quantity that they were pushed far back into the teeth of the wind, and

several times we had to retire still farther off as they bellied out

towards us. It rose to the heavens in immense, writhing convolutions,

and from the centre of the mass huge billows of snow-white steam puffed

out, and bulged

against the smoke, seeming to fight with it for mastery. But as white

and black rose higher and higher in turn they mingled with each other,

and soared up to the skies in a gradually diffusing pillar of grey

which was tilted northwards by the wind and borne off rapidly into the

clouds above.

Here was a wonderful chance to secure a

unique photograph, but on looking round for the coolies I saw them

madly rushing down the mountain-side with my cameras as fast as legs

could carry them. Realising that if I did not stop them I should miss

the chance of a lifetime to get a picture at the lip of a volcano in a

state of violent activity, I ran after them, calling to them to stop.

The guide shouted back that we should all be killed if we did, and they

continued their rush down the mountain-side faster than ever. They

raced over the smooth ash and leapt over stones like deer, regardless

of the damage such a pace might do to my apparatus, which was packed to

suit a more sober gait. Failing to check them with my shouts, I went

after them, and, being unencumbered, soon overhauled the man with my

hand-camera; but he was half crazed with fear, and not all my

entreaties could make him slack his pace. Seeing the chance of a unique

picture slipping away—for I knew the best smoke effects would quickly

be over—I was reluctantly compelled to use a more forcible method,

which had the desired effect. Quickly unlashing the camera from his

pack, I returned with another and older coolie, who had stopped at my

bidding, to the crater's lip, and there hastily took a snapshot showing

Hurley and his camera near the brink, with the smoke pouring out of the

crater in the background. So great had been the rush of air from the

crater, as we were looking over the brink when the outbreak occurred,

that Hurley's panama was carried high up into the clouds, to fall back

into the

volcano—a sacrifice which I think he has never regretted, as the memory

of its tragic end more than compensated for the loss of the hat.

When all danger was over, the coolies,

who were busy haranguing the