CHAPTER X

AN ASCENT OF FUJI-SAN

From the earliest ages Japanese

writers have described the beauty of

Mount Fuji, and poets have sung its charms. The old landscape painters

were so enthralled by the ethereality of the sacred peak that they

painted it from almost every conceivable point—and some inconceivable

points, too—along its southern base. When nearly eighty years of age,

Hokusai, that great immortaliser of the peasant life and character of

his day, published a series of no less than a hundred woodcuts of views

of Fuji in colour, from as many different places on the Tōkaido, and

with as many distinctive foregrounds. Hiroshigé did the

same, and every

other artist in the land, famous or infamous, has at some time or other

been elevated with the desire to portray one or more of the transitory

moods of the beauty under the spell of which all have fallen, but which

none has ever yet been able to delineate with justice.

Other mountains may be painted with some degree of truth—even the

beautiful Jungfrau—but not so Fuji-san. Its loveliness is so delicate,

and its moods so ever-changing and so evanescent, that the most the

artist can ever hope to accomplish is to give some idea of the

mountain's charm at a particular moment. Every nature-worshipper

visiting Japan has fallen in adoration at the foot of Fuji, and foreign

writers and poets have followed their Japanese brethren in attempting

to describe the beauty that has inspired them. Who, that has seen its

snow-clad crest floating in the deep blue of the winter sky, will not

admit that the mountain is worthy of all the praise that has been

bestowed upon it—and more?

It is not only that the

physical charms of the mountain cast so powerful a spell—though they

alone would make of Fuji an object of homage to every lover of the

beautiful in any land on earth—but also that the web of history and

legend spun round the snowy peak is as charming and full of delightful

mystery and sentiment as the moods of the beauty are capricious and

fitful—a combination that marks Fuji as unique among the mountains of

the earth.

Fuji is a dormant volcano, an isolated

cone

12,365 feet in height—figures easy to remember if one thinks of the

days and months that make a year—tapering from a circumference of over

eighty miles at its base to but two and a half miles at the summit. It

cannot be accounted extinct, for at the north-east side of the

mountain-crest the ground is so hot in places that in cold weather

steam may be seen rising from the ash, testifying to the presence of

fissures leading to subterranean fires which may at any time burst

forth again. Geology shows that Fuji is but a young volcano which has

not yet destroyed its beauty by bursting its crater rim—a fate that

usually overtakes mountains of this nature sooner or later. Up to the

present time the only sign of degradation in Fuji's shape is a small

hump on the south-eastern slope. This is the crater Hoei-zan; it

opened up during the last eruption, which began in December 1707 and

lasted until 22nd January 1708.

That was two hundred

years ago; and by most writers Fuji is now referred to as extinct. But

what are two hundred years in the life of a volcano? What are two

centuries in the cooling of the crust of the earth?

FUJI-SAN

In the

story of a planet such an interval is but a passing moment. Vesuvius

was dormant for a much longer period before it laid Herculaneum and

Pompeii in ashes. Indeed, prior to the great cataclysm of a.d. 79

Vesuvius was regarded as an entirely extinct volcano, and was never

looked upon by the inhabitants of the cities at its base, even to the

last moments ere it spread destruction all around it, as the menace

that it ever is to the Naples of to-day. In Japan—this land of

hot-springs, earthquakes, and solfataras—who, with the terrible

calamity which destroyed the sleeping Bandai-san in 1888 still fresh in

the mind, will make so bold as to deny that all volcanoes must be

dreaded? The great Fuji, peaceful as it looks, should yet be viewed

with apprehension. The beauty is not dead, but merely slumbers.

Students of history may see, in some of

the lurid winter sunsets that

dye the snows of Fuji crimson, a reflex of the tragedies in which the

mountain has played a part—for on one occasion at least the sacred

slopes have been steeped in human blood. Towards the end of the

thirteenth century the Mongol Emperor, Kublai Khan, despatched a great

fleet, manned by 150,000 men, to Japan, for the purpose of conquering

the country and adding it to his own dominions. This undertaking was a

most disastrous failure; for the Japanese, aided by the fury of the

elements, scattered the invading hosts and ships, and many hundreds of

the Mongol soldiers were beheaded on the southern side of Fuji.

Thus alike for the fabric of historical associations and legends with

which it is enveloped, and for its symmetry and beauty, does Fuji

inspire and appeal to the Japanese—most aesthetic and imaginative of

peoples—and thus it is that the peerless mountain has formed so

favourite a motive for artists during all the ages since a knowledge of

art was first imported to the land.

As I gazed at Fuji, enraptured, in that

hour when I first saw Japan, an

intense longing settled upon me to climb the mountain, to creep foot by

foot up that glorious outline which sweeps in one magnificent curve

from the sea-shore to the sky, and to look far and wide over the world

below from the very topmost pinnacle of Japan. Two years later I

gratified this wish; and now, a year later still, the mountain's crest

was again my goal.

The train was creeping laboriously up

a steep ascent between hills covered with dense undergrowth and capped

with crooked old pines—rugged, weather-beaten veterans, all twisted,

bent, and straggling—which scorned every law of balance and proportion.

From the tops of their red, reticulated trunks a few gnarled branches

stretched outwards and downwards, with seemingly no regard for any

rules such as govern the growth of well-regulated trees in other lands

; and from the extremities of their distorted limbs a few spiky

needles, in little tufts, stuck out as though bristling with temper,

like the hackle of an angry fighting-cock. By their very defiance of

convention these trees were beautiful, and graced the earth from which

they sprang.

From the pine-clad hills we descended to

rice-fields—carpeted thick as velvet with the verdant spears of tender

new-grown shoots—and thence, once more, up into hills covered with

feathery bamboos, bending to the breeze.

The sites of

the cottages among these hills and dales seemed, one and all, to have

been chosen only after mature and careful consideration with a view to

securing the best and most artistic effect. Each little humble dwelling

stood just where it ought; were it moved either

to left or right the picture would be marred. Made of natural-finished

woods, bamboo and thatch, and standing in a cane-fenced enclosure, each

of these huts was in itself a study.

Before them lay the

terraces and network of the rice-fields. No one who has ever gazed on

the rice-fields of Japan or Java, and watched the seed mature to

ripened ear, will deny that the beauty of the crop, which demands more

unceasing toil than any other that the earth produces, is one of the

principal charms of the lands of all rice-eating peoples.

Descending again from the terraced hills

to more rice-fields, the line

bent round to the south, and as the train pulled up at a country

station the emerald ocean lay before us. It was Sagami Bay, flecked

with the white wings of a score of sampans.

Long glittering waves were

lazily rolling in, foaming as they surged up the pebbly beach, and

receding with long-drawn sighs back to their appointed limits.

Here, also, by the sea as on the land,

everything was typically

Japanese. Near the water's edge there was a group of little children

playing. Hand in hand, with arms outstretched, they were formed into a

ring. The ring was slowly revolving, and a tiny maid stood in the

centre. She was singing, and as her playmates passed her, one by one,

she pointed each of them out with her finger. I could catch a few bars

of the air now and then. It was quite pretty, and sounded to my ears

almost sad, accompanied as it was by the regular soughing of the waves

upon the shore.

Japanese as the sight was, it was one of

those touches of nature that make "the whole world kin." How often

have I seen little children playing such games in England, and other

countries too!

London Bridge is falling

down, falling down, falling down,

London Bridge is falling down, my fair Lady.

Have we not all played such games ourselves, before we knew

what life,

with all its joys and sorrows, its pangs and heartaches, meant? It was

one of those innumerable brief visions, incident to my travels in this

land of happy children, that have made the memories of Japan so dear.

Near-by the playing babies, with the

breaking waves creeping to their

feet, there was a rugged bluff with a few straggling pines leaning over

the edge. One of the pines had leant too far, and was in peril of

falling into the sea; but some thoughtful soul, seeing the artistic

effect of that old tree, bowing to inevitable doom, had placed a firm

prop under it, securely founded on the rock, so that for many years

there would be no danger of the landscape losing a bold and picturesque

feature.

Leaving the placid waters of Sagami Bay

behind

us, the line bent inwards again, and the great Koshu range lay

ahead—blue, dark, and forbidding under the heavy storm-clouds above it.

And now, as the train turned westward, the great Fuji loomed before us,

all black and purple in its summer dress.

Always

splendid, magnificent in all its moods, Fuji on this August evening was

grand and awe-inspiring. To the south the sky was clear, but over the

mountain the heavens were filled with great banks and convolutions of

clouds—white as snow, and, in places, dark as night—and a bright sunlit

mass of vapour behind the mighty peak caused it to stand out black,

frowning and terrible, towering almost to the zenith—a spectacle truly

sublime.

As we drew nearer to the base of the

great

volcano the prospects for a fair to-morrow grew steadily worse and

worse. The lovely billows of cumulus gave way to angry nimbus clouds,

deep purple-grey and blue, which filled the

western heavens.

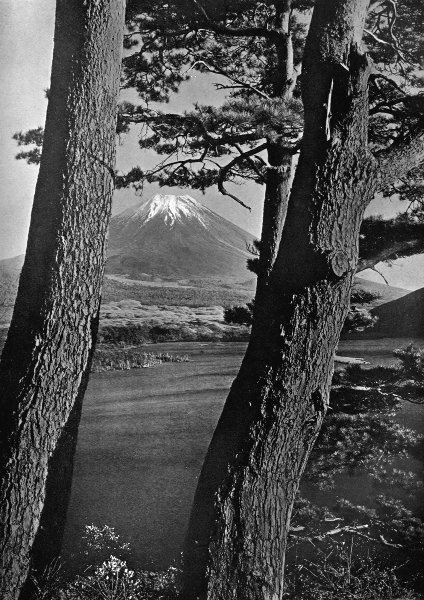

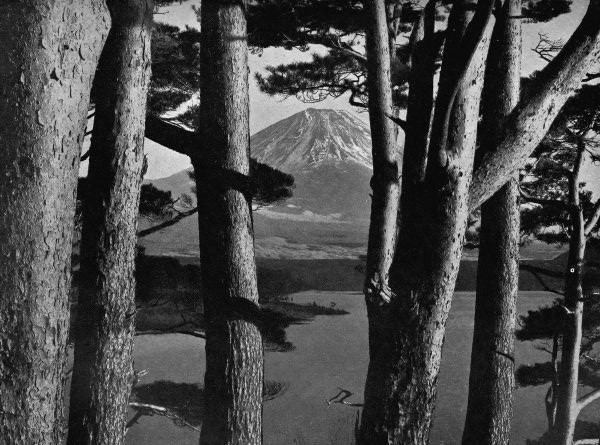

FUJI THROUGH THE PINES OF LAKE MOTOSU

Once, however, the storm-clouds parted, and the dark

brow of Fuji appeared, seeming almost to overhang us, as if threatening

with destruction all who should make so bold as to essay those lonely

dizzy heights: as if the very goddess of the mountain herself

challenged us to dare dispute her right to reign in those altitudes

alone and undisturbed.

We reached Gotemba at 6.30 p.m.,

and our arrival at the Fuji-ya Inn caused a pleasant diversion for the

inhabitants of the town—to judge by the numbers that collected in front

of the hotel, awaiting with interest the result of our discussion as to

whether it would be better to remain at Gotemba for the night or push

on, as we had intended, and sleep in one of the rest-huts on the

mountain-side. We decided to have supper and think it over. The inn, we

found, was full of guests—Japanese pilgrims en route to do

homage to

the goddess of the mountain by worshipping at the shrines around the

crater's lip.

Mount Fuji is officially "open" only for

three months of the year—July to September. To undertake the ascent at

any other period would entail much trouble and expense. During the

"open'' season many thousands of pilgrims annually make the ascent, for

at that time it may, if desired, be made in easy stages, as there are

rest-huts, called go-me,

where food and a shake-down for the night may

be obtained, at approximately five, six, seven, eight, nine, and ten

thousand feet. Some old people, who undertake the pilgrimage as a

climax to a life of religious devotion, take a week or ten days over

the ascent, painfully and perseveringly accomplishing a thousand feet

or so each day. This being the "open" season, and Gotemba one of the

favourite starting-points for the climb, accounted for a large number

of pilgrims at the inn that night. Inquiry

of the landlord elicited the information that there were over

seventy—as many being crowded into each room as it could be made to

hold.

Supper over, any further discussion as

to the

wisdom or otherwise of starting that night was superfluous, for,

through the open window of the room that had been assigned to my

Japanese interpreter, Nakano, and myself, we watched the storm-clouds

growing momentarily more threatening, until the skies were black as

pitch, though the moon was full. Presently a blinding flash of

lightning rent the heavens, and, from the terrific crash that

simultaneously accompanied it, it seemed almost as though the crack of

doom had split the earth itself. The long-gathering storm had burst at

last, and even if the cyclopean forces that formed the great volcano

had been loosed once more, the spectacle could hardly have been grander

than the battle of the elements that we witnessed during the two

succeeding hours. The lightning danced, and flickered, and flashed over

the whole vault of heaven, and the thunder for an hour was incessant.

Many of the pilgrims seemed overcome with fear, and crowded together in

the rooms and passages, loudly repeating prayers in whining sing-song

tones. At length the tumult ceased, and we betook ourselves to the

futons

(padded quilts) to get well-needed rest, preparatory to the

tedious work of the morrow.

At 3 A.M. the bustle and

clatter of the pilgrims, who were preparing for an early start, woke me

; I got up to find the sky clear, and Fuji blocking out a great

triangular space in the starry heavens, its whole outline brilliantly

illumined by the soft light of the moon. I lay down again, and slept

till five, when the little neisan,

who had come in to wake us, exhorted

me to look at Fuji, which, to my delight, was still in gracious mood,

displaying its

charms without reserve, and though snowless, save for a few patches,

looked lovely, and all pink and violet in the early morning atmosphere.

There was much ado about making the

preparations for the ascent, as it

was necessary to secure the services of four lusty coolies to carry my

photographic apparatus, portable photographic dark-tent, supply of

plates, blankets, change of clothing, and food sufficient for five or

six days. I had come prepared to stop several days on the mountain, if

necessary, in order to secure the views I coveted from the summit. The

food to be got at the rest-huts is of only the coarsest kind; and I

hoped my own supply would prove amply sufficient, so that I might not

have occasion to resort to it.

Whilst Nakano was

engaging the coolies, I amused myself by inspecting the pendant flags,

with which the front of the inn was arrayed. These are, strictly

speaking, not flags at all but towels. They are often the

advertisements of tradesmen, who hang them up at the hotels at which

they stay, or by the fountains of Buddhist temples, or near some Shinto

shrine. These towels, in addition to having the merchant's name and

business described on them, are frequently of very dainty and artistic

design. By hanging them up at the temple fountain a double duty is

performed. A service is rendered to the temple in the gift, trifling

though it is, of a towel, so that those who cleanse their fingers and

lips before entering to pray may have the wherewithal to dry them with;

and a very excellent advertisement is obtained by placing on the towel

an efivective design with the donor's name and business description.

The inscription cannot escape the attention of the user, as the towel

is always suspended by a string and a thin piece of bamboo, so that it

hangs straight, and can therefore be easily read. Similar towels are

also

used as banners by pilgrims, who donate them to each inn at which they

put up, thereby publishing the enterprise of their own particular club.

Gotemba is not an interesting town. It

is not even picturesque, but is

very mean and poor-looking, and lacking in any single feature except

the view of the glorious mountain to which the town owes its existence.

The inhabitants look to make sufficient earnings,during the months the

mountain is "open" to keep them for the remainder of the year. The town

itself, therefore, merits no further notice, nor do the inhabitants,

for they are as lacking in interest as the place.

Nakano

having secured the services of three brawny luggage-carriers, called

gōriki, on

each of whose broad backs about forty pounds of luggage was

strapped, we left Gotemba at 7 a.m. and took to a cinder path through

rice and corn jfields. Straight ahead of us the great Fuji towered to

the very skies, and it seemed a hopeless task to expect to reach the

summit that night. We had proceeded a ri (a Japanese ri is 2½

miles) on

our way when I found that an important part of my photographic kit had

been left behind. There was nothing to do but return for it, which I

did, running to the hotel and back again. This took up nearly an hour,

and doubtless had much to do with the fatigue I felt later on.

From the rice-fields we tramped over a

rising moor, covered with long

grass and studded with stunted pine-trees, where birds were twittering

everywhere in the soft balmy air. Little bunches of detached cumulus

floating in the sky threw patches of moving shadows on Fuji's slopes,

and these clouds, gathering about the summit, presently obscured it

from view.

By ten o'clock we were well up in the

forest and undergrowth that clothes the lower slopes.

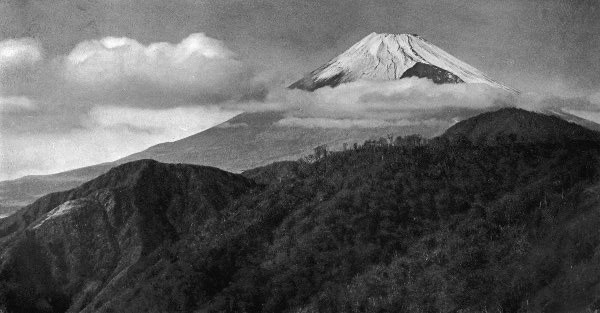

FUJI FROM NAKANO-KURA-TOGE

Looking backwards, the great

barrier range of Hakoné was a poem in greens of every shade,

with a

belt of silvery clouds floating lazily in from the west and lightly

touching every peak. Sometimes the clouds above us parted, and we saw

thick mists settling in the ravines which scar the upper heights. These

mists were white as the streaks of snow, so that we could not

distinguish where snow ended and mist began. It was a pretty sight, and

gave the mountain the appearance of having donned its winter dress.

At eleven we reached Umagaeshi, or "Horse Return." Formerly those who

came on horseback had to leave their steeds behind at this point, and

make the rest of the ascent by foot, as above this place the mountain's

slopes were held to be so sacred that no horse's foot might tread it.

In former times, too, women were debarred from ascending the mountain

higher than the eighth rest-house. These old rules, however, have

lapsed of recent years. Now, those women, who can, may ascend to the

top with impunity; and hundreds of pilgrims, who do not care to put

too great a tax upon the nether limbs, ride on horseback as far as the

second rest-house—a good two hours' tramp farther up the mountain.

Indeed, so profaned has Fuji become that

in 1906 a Japanese, under the

incentive of a wager, rode a horse to the summit—a feat which called

forth much protest from the press. Strange to say, however, this

protest did not take the form of an outcry against the violation of

ancient traditions, but was raised merely on the ground of cruelty to

the horse. This was somewhat unreasonable, as there was no climbing to

be done by the route taken, and therefore no reason why the horse

should not accomplish the journey—which it did, without suffering any

ill effects whatever. In the Himalayan passes horses are worked at much

greater altitudes than the

summit of Fuji. A protest on such grounds was the more remarkable as

the Japanese horse is by no means the best treated equine in the

world—or even in the East—and is, as any foreigner who has travelled

much in

Japan can testify, but too often the victim of ill-treatment and abuse.

We reached Tarōbō, 4600 feet above

sea-level, at 11.15. This was not

such rapid progress as I had hoped to make, but the gōriki

complained

that they could go no faster, as the loads they carried were so heavy.

Tarōbō is an interesting spot, with a large and substantial rest-house,

where we had some tea and rice. The place derives its name from a

mountain goblin who was formerly worshipped at a shrine near by. One

may purchase here, for the sum of 10 sen, a staff such as is used by

all pilgrims who ascend the mountain. These staves are marked by a

burnt impress of the name of Fuji-san, in Chinese, and at the summit

the residing priest adds a further impression.

The view

below us, as we rested here, was exceedingly beautiful. The waters of

the rice-fields glistened in the sunshine, and the atmosphere was so

clear that, with my glass, I could easily pick out every detail of the

houses along the old Tōkaido highway. Snowy clouds floating in the

azure added greatly to the charm of the scene; and the line of fluffy

billows over the Hakoné barrier had lifted, so that between

them and

the mountain-tops we could see the end of Ashi Lake, flashing like a

jewel in the sun, and, far beyond it, the blue waters of Sagami Bay, in

which a single tiny speck marked the sacred island of Enoshima, distant

about forty miles from where we stood.

At Tarōbō we left

the pleasant green and shade of the woods behind, and emerged suddenly

on to the desolate waste of ashes up which we must toil for over seven

thousand feet of height, and along a zigzag path of more than

fifteen miles in length. It was indeed a dreary prospect. Yet it was a

wondrous sight which burst upon the vision as we left the grateful

woodland. A vast expanse of cinders stretched before us, slowly-merging

from black at our feet to purple-grey, where, miles and miles away, it

lost itself in cloudland. It was a burnt-up sea, with waves, and

ridges, and hillocks of pumice and scorias, in which the torrential

rains that deluge the mountain-slopes had torn great clefts and deep

ravines. From this point to the top, the mountain sweeps in one

beautiful unbroken curve—a curve so perfect and even that it reminded

me of the wire rope, bending of its own weight, down which loads of

firewood are sent across the Nekko River to Furuseki from the mountains

on the opposite shore.

As we struck out on to this

barren waste the heat absorbed by the black cinders was terrific, and

with the hot August sun scorching down on our backs the ascent of even

so easy a mountain as Fuji became no joke. That toilsome journey to the

top of Europe is not more laborious than the weary tramp through these

interminable ashes; and the two mountains offer strange and striking

contrasts. Mont Blanc is white—a colossal pile of ice. Fuji is black—a

stupendous heap of cinders. One may sit on the hotel verandahs at

Chamonix and through great telescopes observe, occasionally, a few

black specks—like a little string of ants—creeping slowly, almost

imperceptibly, up the virgin snows of Mont Blanc. As we left all

vegetation behind us, and set out on the now desert slopes of Fuji, the

mountain ants were here too, only there were many more of them, and

they were white ants instead of black ones, and crept amongst sombre

ashes instead of stainless snows.

Tradition says that Fuji rose from a plain in a single night, when a

great depression appeared in the earth, a hundred

and fifty miles away, which is now filled by the waters of Lake Biwa.

That a volcano may have been formed here in a single night is likely

enough. Who can say? But that it arose from a plain is clearly a myth,

for a mile to the right of the second rest-hut there is a deep rift

disclosing solid masses of rock, quite different from any other found

on the mountain. These rocks appear, without doubt, to be the summit of

some lesser peak which this mass of ashes has overwhelmed, and a chain

of hills running from the south-east to this spot seems to confirm the

theory.

The heat—which had been getting almost

intolerable, for there was scarcely a breath of wind—was now gratefully

tempered by clouds which came between us and the sun, and our progress

at once became more rapid. We reached the ni-gō-me, or second

rest-hut,

at one o'clock, and rested for twenty minutes. On starting again we

plunged into mists which came swirling down the mountain from every

point of the compass, formed by some rapid barometric change that

caused a cool, refreshing wind to blow. For this we were all very

thankful, as it was a great relief after the sun's demonstration of how

painfully wearisome he could make the journey up these soft

heat-absorbing slopes.

The trail up the mountain was

well bestrewn with waraji,

those cheap and serviceable straw sandals

which every native of Japan uses when travelling in country districts,

and of which I had come provided with a good supply, of a size

sufficiently large to affix to the soles of my boots. They not only

afford a good grip on the loose cinders, but give very necessary

protection to the leather, which would otherwise speedily be torn to

pieces by the sharp, rough clinkers. Even with the protection afforded

by waraji,

Fuji is "good" (?) for one pair of boots, and I would advise all who

follow in my

footsteps not to wear boots by which they set any store, as after the

descent they will be of little use for further wear. The right footgear

for a trip up Fuji is a good, comfortable pair of old boots and several

pairs of waraji.

Two pairs of the latter may be reckoned on for the

ascent, and about four pairs for the descent. Leather leggings are

better than stockings, as they prevent the small cinders—in which, on

the descent, one's feet are continually buried—from entering the boots.

The Japanese never use boots for mountain work. They wear blue cloth

socks, with a separate compartment for the big toe, and waraji tied to

them.

At 3.45 we reached the fifth gō-me (8659 feet),

with over 3500 feet to go. I was glad enough to stop here and have a

cup of hot cocoa, as the mists that had enveloped us were damp and

chilly. Owing to the altitude and heavy going, and to the fact that we

could not leave the gōriki

behind, as they seemed intent on loafing, we

had not been able to proceed fast enough to keep warm. I had started

out in summer clothing, suitable to the heat of the plains, and now,

being quite insufficiently clad for these raw, driving mists, was

shivering with cold. Whilst the gōriki

rested I got out some thick

woollens and clothed myself more suitably for the great change in

temperature.

As we were leaving the fifth hut the

mists

parted, disclosing Lake Yamanaka bathed in sunshine and reflecting the

clouds above it. The clouds overhead also melted for a few moments, and

there was Fuji's crest as far off as ever it was a good three hours

ago, when we had last had a glimpse of it. Surely we had not moved an

inch, or else the mountain was ascending too!

A band of descending pilgrims—laughing, shouting, and singing, in high

spirits at having accomplished their mission—came running and leaping

and glissading down the straight

path of the descent. The ascending path is zigzag, the descending one

is straight.

Nearly an hour earlier, as we met

another descending band, I had shouted in Japanese, "How far is it to

the top?''

"Three ri," one of them

replied.

Now again I put the question as the

merry pilgrims passed me. "How far to the top?"

"Three ri,'' came the

answer.

I knew it. The summit was as far off as

ever, and looked it. Without

doubt, the mountain was getting higher as fast as we were scaling it.

At this rate we should never reach the top. Thank heavens, we were at

least keeping pace with it!

By half-past four the

clouds had cleared away, and the whole upper Fuji was visible. We were

well above the waist—in the middle of the great sweeping curve taken by

the slope from the mountain-top to Tarōbō. From a distance this curve

is not very perceptible, but from where we now were we could see how

great was the deviation from the straight line. Away to the west the

mountain outline was much steeper, and perfectly straight—a

stupendous incline which shoots up at a dizzy angle into space.

How weary this interminable zigzag was

getting! Mile after mile there

was no variation to the monotony of turning its everlasting corners.

Several times I tried to relieve the tedium by making short cuts,

straight up; but as soon as I left the beaten track the cinders

slipped under my feet, and progress was slower than ever. At 5 p.m we

were at the sixth gō-me,

9317 feet above sea-level. We had scarcely

ascended 700 feet in three-quarters of an hour. It sounds slow, and

would have been so if the rest had all been as unhampered as I; but

each goriki's

load was a third of his own weight, and our pace was that of the

slowest member of the party.

Some rollicking students from Tokyo

University were making the mountain

ring with their songs, and a number of pilgrims, too, had settled in

the rest-hut for the night. These pilgrims, who flock from all over the

land to Fuji in summer, are mostly of the rustic class. They are very

poor, and are assisted on their mission by funds furnished by clubs to

which they belong, and which are found in every village. The members

pay trifling annual subscriptions, and each year lots are drawn to

decide who of their number shall visit certain holy places. Many of the

pilgrims are dressed in white, with broad-brimmed hats, shaped like

Fuji, made of straw. Each carries a staff, bought at Tarōbō—which,

when the mission is over, will become an heirloom in the family—and a

large piece of matting tied to his back. This projects at each side,

and as it flaps about in the wind gives him a most droll appearance,

like a young chick trying to fly. This mat acts as a waterproof coat, a

shield to keep the sun off his back, and, at times, as a bed—if, as is

often the case, he finds the available supply of futons already

engaged

on his arrival at the rest-hut. Each pilgrim has also a tiny bell tied

to his girdle. Thus when the mountain is "open" and the weather

favourable, its slopes on the Gotemba and Subashiri sides—for Fuji may

be ascended with comfort only on certain well-kept routes—are all

a-tinkling with these little sweet-toned bells. As the pilgrims slowly

wend their way upwards they continually sing out, in sharp, staccato

accents, the Shinto words "Rokkon

-Shōjō, Rokkon-Shōjō''—a formula

signifying the emptiness of life, and conveying the exhortation to keep

the body pure. Can the reader imagine a party of Alpine mountaineers,

ascending the Jungfrau or Mont Blanc, shouting to each other, as they

slowly toil upwards midst snow and ice,

a prayer to cleanse themselves from sin? Yet there are people who look

upon the Japanese as uncivilised heathens!

"Rokkon-Shōjō''

is an abbreviation of the formula "Rokkon

-Shōjō O Yama Katsei," which means, "May our

six senses be pure, and the

weather on the honourable mountain fine." Professor Chamberlain says

that the pilgrims "repeat the invocation, for the most part, without

understanding it, as most of the words are Chinese.'' When the full

formula is used, it is chanted antiphonally, sometimes between bands of

pilgrims a mile or more apart, as sound carries a long way on the

mountain-side. It is usually abbreviated, however, to the first line.

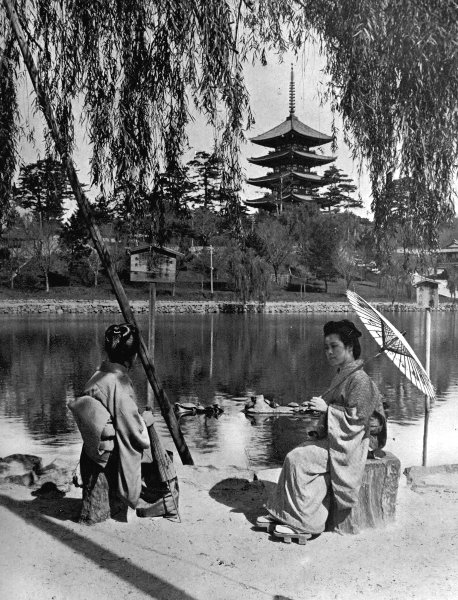

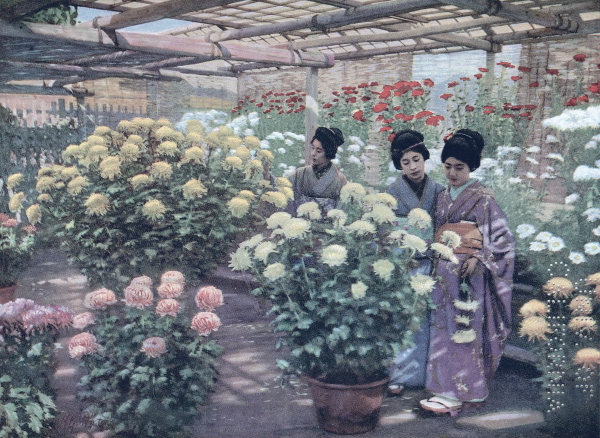

The Japanese are very fond of summing up

abstruse sentiments into a few

words, and also of embodying abstract ideas into concrete forms—as, for

instance, in the case of a pagoda. A five-storied pagoda is

emblematical of the emptiness of life. Five is a mystic number. The

pagoda has five stories. The universe has five elements. The body has

five senses (which are, however, to the Japanese mind, enclosed in a

sixth sense—the body itself). Everything in the world is composed out

of one or more of the five elements—fire, earth, water, air, and

ether. The human body especially is a combination of these elements, to

which, when life is extinct, the body returns. Thus does the pagoda

typify the unsubstanti-ality of all earthly forms. The body, being but

worthless, temporary trash, should be resolutely combated and

mortified, and care given only to the soul. All this and more is borne

to the Japanese mind by a five-storied pagoda; it is likewise all

summed up in the pilgrim's cry, with which the slopes of Fuji ring, of

"Rokkon-Shōjō."

THE NARA PAGODA

At 6 o'clock we reached the

seventh rest-hut, and found it closed. The

panorama below us was beautiful beyond the power of language to

describe. Little fleecy tufts of cloud lay about the world below us as

if great bales of cotton had been torn to pieces by the gods in

Olympus, and scattered o'er the earth. The sun, long since gone over

the mountain, and now nearing the horizon, was turning the fleece into

golden foam, and Yamanaka Lake, steeped in shadow, peeped between the

foaming wavelets, grey and smooth as 5teel. Far below us, and now many

miles away, the forests looked soft and sleek as velvet, and above,

Fuji's crest was blue and violet against a turquoise sky.

The trail of the ascent is intersected

at the seventh gō-me

by a path

called Chudo Meguri, which encircles the mountain. Many Japanese

nature-worshippers make the circuit of Fuji by this path. It is about

twenty miles round, and the journey takes about eight hours. So far as

observation of the scenic effects is concerned, there is no object in

ascending higher, as from the summit everything appears more dwarfed,

and is liable to be obscured by haze.

Above the sixth

rest-hut the ascent becomes rapidly steeper, and the mountain is

bestrewn with great blocks of lava. I would fain have made more rapid

progress, but my gōriki

were evidently not moved by the enthusiasm that

urged me on, and kept up the steady plodding gait which they knew by

experience is the pace that lasts.

Those of my readers

who have spent holidays in the Alps, and have slowly fought their way

up some icy peak, will know the steady mechanical pace set from the

outset by the Swiss guides. Probably, before they knew better, they

wanted, as I did, to go faster, much faster, but were kept in check by

the men to whom this is no pastime but the business of their lives. It

is the only way to scale a mountain—to adopt a slow and

steady pace and keep it up like a machine; and it is marvellous what

that slow, steady gait will accomplish. Hour after hour you plod on, so

slowly and so surely, yet, imperceptible as the progress is, eminence

after eminence is gradually gained in the silence of deadly earnest,

broken only by the crunching of your boots and the squeaking of your

ice-axe, as, using it for a staff, you plunge its point at each step

deep into the snow. The light of the moon that helped you on your

midnight start now pales, the sky becomes grey, and the grey gives way

to pink and amber as the sun rises; but still you plod . on, stepping

in the footprints of the guide in front. At last, almost before you

realise it, the fight is over. Your pulse beats quick and strong, and

your whole body glows—not only from the effects of the exertion, but

with the joy of knowing that you have achieved your ambition. You have

gained, for the time being, the height of your desire; and, from the

topmost pinnacle of that icy finger which beckoned to you from the

skies, you can revel in joy undreamt of by those who have never sought

the solitude of the mountains, and the glorious pleasures which it is

in their power to bestow on those who love them.

So it

is with Fuji too—steady perseverance tells, and only by its exercise

can the crest be won. My gōriki knew this, and could not be urged to

change the pace which had become to them a habit. Moreover, to them the

ascent had no incentive of novelty. These men were mountain porters for

three months of the year, carrying supplies to the rest-huts. Between

the four of them they could aggregate over thirty ascents that year to

the top, besides a greater number of journeys to the lower stations,

although the resthuts had scarcely been open a month. Small wonder is

it, then, that they were not to be carried away by enthusiasm.

How wearisome this plodding was becoming

! How steep the mountain was

getting! I was beginning to feel tired, too, and marvelled how those

fellows could do all this with those heavy packs. They must have sinews

strong as wire. The mountain was so steep now that care had to be

exercised not to disturb the stones; otherwise they might roll down

the slope, to the danger of some one below. My feet were getting very

heavy, and my thighs beginning to feel sore at the unwonted tax upon

the muscles. The clinkers were rougher and sharper at every step.

Should we never reach that eighth gō-me

?

The gōriki

were tiring too, for they had been going very slowly and were now

stopping to have a smoke. I began to suspect them. Were they conspiring

to try to induce me to stop for the night at No. 8? I knew very well

that they were used to transporting greater loads than this from

Gotemba to the top in a day, so I determined to reach the top that

night; I would not be cajoled out of it. I dared not stop to admire the

view. That would be fatal. I must not waver till No. 8 was reached, or

they would suspect me of being as tired as I was. These thoughts

spurred me on to renewed efforts, and at last I reached the hut,

ordered some tea, and refrained from sitting down for fully five

minutes—an act of self-denial which called for all the will-power I

possessed—in order to deceive the gōriki,

who I knew were closely

watching me, as to my real condition. I lit a cigarette and walked

outside to smoke it, scarcely thinking I had it in me to dissemble

thus. The eighth hut is 10,693 feet above the sea, and about 1500 feet

from the summit rest-house, which is in a hollow on the mountain-top,

some 200 feet below the highest point. The sun had

long since set behind the mountain. The turquoise sky had turned to

coral and amber, and Japan below was growing dark and being covered by

the mists of night, which were spreading lightly over the earth, like a

robe de nuit.

It was only a thin stratum, however, and through it rose

the peaks of Ashitaka-yama, O-yama, the Hakoné range, and

many others,

seeming to float like romantic isles in a mystic sea of legend. The

daylight died rapidly as I watched, and a radiance over the "Maiden's

Pass" in Hakoné foreshowed the rising of the moon. Darkness

was

gathering fast, and faintly shimmering stars pierced the opalescent

heavens. The luminous east turned silver, and, whilst yet the

after-glow was burning in the zenith, the moon peeped over the ocean's

edge and threw a dancing shaft of light across Sagami's waters to the

rugged coasts of Izu. Only to have seen this glorious sight had been

more than worth the journey. A hundred times had I gazed on such scenes

depicted in golden lacquer, and wondered at their beauty. Now for the

first time I saw the reality that inspired them.

As I

anticipated, the gōriki,

who had arrived during my contemplation of

these wonders, complained of fatigue, and said they could go no farther

that night; but I put on a firm front at once and declined to consider

breaking the journey. I was really anxious to reach the top and record

a few impressions before turning in, so I offered them each 50 sen

extra if we were on the summit by nine o'clock. As we started off from

No. 8 my suspicions that they were merely "playing possum" proved to

be well founded, for such was now their accession of enthusiasm to

reach the top as soon as possible that I was hard put to it to keep

ahead of them.

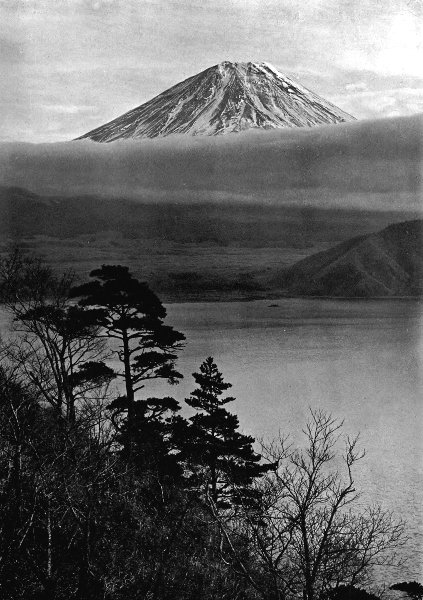

FUJI AND THE PINE TREES

The incentive of an extra shilling each had worked marvels in

dispelling their fatigue.

By this time the moon was shining

brilliantly, and near by the trail

one of the snow-patches, which had seemed but a mere spot from Gotemba,

was a quarter of a mile in length, and had a ghostly glimmer amidst the

surrounding blackness. Above and all around us were great masses of

slag and lava. Weird and unearthly-looking was this holocaust of

hideous shapes—this vomit cast up by the mountain in the throes of its

agony and fever. The path was much harder and firmer now, but

exceedingly steep; and every step amongst the eerie shadows was

bringing us visibly nearer to the crater-lip above. My heart was

beating with loud thumps against my ribs, and my head ached badly, the

result of the elevation and rarefaction of the air. We slowly passed a

great gully, looking black and bottomless—a yawning chasm which from

the world below was but one of those creases that serrate the

mountain's edge. Then the sky-line appeared just above us. Another

moment's scramble—one last and final pull—and I stood on Fuji's crest.

It was 8.40 P.M. The rest-house was

scarcely a hundred yards away, and

the gōriki

with their loads went unconcernedly on, without once looking

behind them. As for me, I was content to sit awhile where I was, and

survey the scene about me. It was freezing hard, but not a breath of

wind stirred the air, and the heavens were scintillating with

glittering diamonds. For every star I ever saw before there were now a

thousand, all shivering in the firmament and adding soft radiance to

the rays with which the moon strove to pierce the blue-black void

below. There was no robe

de nuit

over the earth now. It had dissolved

away, leaving nothing but inky blackness, parted by one great streak of

silver where the rapid Fujikawa raced onwards to the sea.

Around me was naught but distorted

shapes, and space, and silence.

Though I strained every faculty to catch some faint murmur from the

world below, naught but silence absolute and supreme fell upon my

ears—a silence broken only by the loud pulsations of my heart, which

smote the air with great resonant thuds. It is something dread and

awful, this vast, tremendous hush. It is the infinite calm of great

altitudes and depths.

Once, in my mining days in

California, a desire seized me, in the dead of night, to descend the

shaft alone, when no other living soul should be there. The thought was

but the parent of the action. Hastily putting on some clothes and

donning my overalls, I went over to the shaft-house. It was a stormy

night, and rain was clamouring on the sheet-iron roof. I lit a candle

and groped my way rapidly down the steep incline of the shaft. Five

hundred feet into the crust of the earth I went, and felt no new

sensations except one of disappointment as the shaft echoed with my

footsteps. Six hundred feet, seven hundred feet, eight hundred feet and

the bottom of the mine! It was not worth it. I had taken all this

trouble for nothing, and now I had to toil all that weary way up to the

top and the rain and the mud again.

But as I stood there

a creepy feeling came over me. What was this consciousness that

suddenly oppressed me, and made my blood seemed chilled? I had felt

nothing like it before. My candle gave but a feeble glimmer, and I

found myself peering furtively into the shadows with a feeling almost

akin to dread. All at once I knew; it was the silence—the immense,

oppressive silence. Hitherto, whenever I had been down the mine there

had always been the regular beating of the hammers on the drills. Now

there was nothing but thick, velvety silence.

Then a sudden sound, like the crack of a

stockwhip, put every sense on

the alert. Was I not alone, then, after all? In a moment the instinct

of self-preservation reminded me that I was unarmed. Who could be down

here at this hour, and what could be his object? Had I been followed?

Without a weapon I was at the mercy of any ruffian, and powerless as a

rabbit in a hole. All this rushed through my brain in a moment, and as

I tried to pierce the shadows my candle only served to make the

darkness visible. Another crack—almost like a pistol shot—and then

enlightenment and relief flashed upon me. It was nothing but a drop of

water falling from the hanging-wall into the sump below; yet, in this

dread silence, it struck with almost the detonation of a fulminating

cap. I knew then why great burly miners sometimes refuse to work alone

in distant drifts. I never could understand before, but now I knew; it

is the silence that they fear.

As I listened for that

intermittent drop, falling with the regularity of a minute-gun paying

the last tribute to a soul gone to rest, tales of horrible things came

to mind. In China, it is said, the very refinement of torture is to

confine a condemned criminal in a place to which no sound can

penetrate, and over the plank, to which he is bound, to place a vessel

of water, so regulated that once every few minutes a single drop shall

fall upon his brow. There being no light, and no sound to distract his

attention, the poor wretch's senses become so concentrated in

expectation of the next drop of water, that, when it falls, it seems to

strike him with the impact of a bomb, and reason cannot long withstand

the strain.

Shivering with cold after these reveries inspired by the stillness, I

went into the rest-house, and soon a meal was ready

and steaming hot. Too tired to go out again that night, I was glad

enough to take to my rugs and futons

and get to sleep.

From this point I quote from my diary

written during my stay on the mountain top.

August

3.—I told the hut-keeper last night to be sure and call me well

before sunrise if the weather was fine, but when I awake it has long

been daylight, and I have a racking headache. The wind is whistling

round the hut, which is in a sheltered hollow, and hail is pelting on

the roof. I get up, and we all crowd round the charcoal fire and have

breakfast. There is another fire where wood is burnt for cooking. The

fires are near the door of the hut, which is wide open, on the most

sheltered side of the building. Outside nothing can be seen but

swirling mists and driving snow and hailstones.

August

3, Noon.—As hour after hour passes, the storm increases. Fortunately I

have a good supply of canned provisions, and bread sufficient for

several days. Nakano is lying down, wrapped up in futons, overcome

with

mountain sickness. The gōriki

are all huddled up in a corner of the

hut, completely covered, heads and all, with futons.

August

3, 2 P.M.—The storm is worse. I am evidently destined to

incarceration here for a day or two at least, so I may as well record

my impressions of the place which forms my prison. The house is neither

remarkable for its comfort nor its elegance, but is strong and

weather-proof. It is constructed of blocks of lava, each block being

chiselled so as to fit in exactly to its neighbours without mortar to

bind it. The walls at the base are three feet thick, sloping on the

outside to a width of one foot at the top.

THE CREST OF FUJI

A Telephotograph from a Distance of 15 Miles.

The interior is tightly

lined with boards, and a solid framework of

wood, braced with iron, supports the roof, which is the least

substantial portion of the structure, being made of one-inch planks

covered with tin from kerosene-oil cans. Plainly it is only the

ampleness and number of the supports that enable the roof to carry the

weight of snow it must have to bear in winter. A portion of the

building is taken up by a large pile of snow, which constitutes the

water supply. The floor is of crushed cinders, and a raised dais—made

of boards, and covered with tatami

(padded mats)—on which the guests

wrap themselves in blankets and futons

to sleep, runs the whole lengtth

of the building. There is no chimney, and the smoke from the burning

pine-wood diffuses itself most effectually into every corner of the

structure.

August

3, 4 P.M.—Twice during the afternoon I

ventured outside the little compound enclosing the hut, but had to beat

a hasty retreat, for icy winds were tearing over the mountain, and I

could scarcely stand. I venture a third time when the wind has subsided

a little, and find the building has two wings, the central portion

being occupied by an old Shinto priest who sits and waits for the

pilgrims who, in fine weather, are continually straggling in to have

their staves and garments impressed with the outline of Fuji's top—the

hall-mark so envied by the pilgrim element of Japan. The postcard craze

has penetrated even here. I buy some postcards from the old priest,

direct them to friends, and have them stamped with the impress which he

places on the pilgrim's garments. The first gōriki going down

will take

them.

The gōriki

haven't moved all day except to unearth

themselves from their futons

once to eat. I don't suppose they care how

long the storm lasts. They are paid by the day, and are having an easy

time of it. It is quite evident they are not worrying about the

weather. Why should they? They are probably dreaming about their

accumulating

wages. Nakano, however, is very unhappy, though. Poor fellow, he is

suffering greatly with headache and sickness from the altitude and

smoke. He has lent me Lafcadio Hearn's book Kwaidan, which he

fortunately brought with him. It is a collection of tales of Japanese

superstitions and imaginations, and the talent of the gifted author

thus enables me to pass away the weary hours delightfully, as indeed it

has often helped me before, under much more favourable conditions. The

weird tales possess an added interest as I read them whilst storm-bound

on the highest part of Japan, from which so much legend and

superstition emanates.

August

3, Sunset.—With darkness

the storm increases again. Two pilgrims have come in during the

afternoon, having struggled up from No. 8 in five hours, and are

stopping here to-night. They have, of course, no alternative. There are

less expensive huts on the north-east side of the crater, but it would

be as much as their lives are worth to try to reach them.

The chronicles of Fuji show that about sixty years ago a number of

pilgrims were caught in dense clouds on the mountain-top and lost their

way. The clouds were but the precursors of a typhoon, which broke

suddenly and with terrific violence. When it abated, and the weather

cleared, the frozen bodies of the pilgrims, to the number of over

fifty, were found closely packed together, showing that they had kept

united to the last for warmth and companionship in that dread hour.

This is but one instance of the many sacrifices that Sengen Sama, the

goddess of the mountain, has demanded of the faithful. The place where

they died is now called Sai-no-Kawara, or the "River-Bed of Souls.''

It is always covered with hundreds of stone cairns, raised to the

memory of these martyrs by those who follow more fortunately in their

footsteps, and in tribute to Jizo, the children's guardian god.

It occurs to me to offer, for the

benefit of those who aspire to

undertake this expedition, some seasonable advice and warning. When you

come to Fuji be sure to provide yourselves with several large sheets of

Japanese oil-paper, and do not forget your gun and powder. I do not

mean by this to imply that you should bring a muzzle-loader, nor yet

that you may expect any shooting. The weapon I refer to is what is

known as an '' insect-powder gun," and the powder I mean is "Keating's"; the former is an ingenious little contrivance for

sprinkling the latter effectively. These precautions are to be directed

against the entomological onslaught which is certain to ensue the

moment you lie down in any of the rest-huts. Well sprinkling the mats

around me, therefore, and spreading a huge sheet of oil-paper on them,

I make my bed, and for the second night lie down to sleep, drawing

another oil-sheet over me as an additional protection. Thus only can I

rest with any degree of comfort.

August

4, 7 A.M.—The

storm is now a hurricane. For hours I have scarcely slept a wink, and

have a splitting headache—due to the rarefied air. It is 7 A.M., and

every one is buried deep in futons.

The piteous rising and falling

cadences of the wind are dismal to hear, and they have now become an

almost incessant shriek. Now and then there is a moment's lull, but it

is only the storm-fiends drawing back to make a fiercer, more

determined effort. Gathering all their strength, the winds rush upon

the structure, and smite it terrific blows. But the solid, well-braced

walls resist the fiercest onslaughts, and do not give the fraction of

an inch; there is scarcely even a tremor; and the furies, baulked of

their prey, go tearing past, screaming and howling in impotent rage. I

would not have missed this for a good deal. I may never have such an

experience

again, nor do I wish to, but to be on Fuji's crest when the mountain

is in the angriest of its moods is something to remember. When the wind

woke me, and I lay in tht futons,

listening to its onsets growing

momentarily fiercer, I was somewhat ill at ease; but now all anxiety

is gone, and my confidence in the staunchness of the hut grows stronger

as each fresh assault is baffled.

August

4, 9 A.M.—We

all get up and breakfast. The wind seems to be lessening. I have

finished Kwaidan, and must read it through again. I have nothing else

but Murray's Handbook—best

of all guide-books on any land—but I know

much of it almost by heart. Nakano is still suffering greatly, and says

if it were only possible to descend, he would have to go down.

Mountain-sickness is a very painful thing. I have had it on Mont Blanc

and know what it means. One of the pilgrims who came in yesterday had a

dreadful cold. He was sneezing almost incessantly, and thought he was

going to die. I took him in hand and gave him a strong glass of whisky

and hot water and ten grains of quinine. I had great difficulty in

getting him to take the whisky, but he didn't mind the quinine pills.

This morning the cold and fever have left him, and he thanked me with

brimming eyes. He said he knew I had been sent by the gods to save his

life. If I had the missionary instinct I might be embracing the

opportunity by devoting the day to securing a jewel for my crown. But I

am not a missionary, and I am doing nothing of the kind. On the

contrary, I am reading Kwaidan

again, the author of which, if he had

any religion at all, which is doubtful, was a Buddhist.

Our host is the very model of the

virtues of patience, apathy, and

taciturnity. All day long he sits and smokes, and smokes and sits, and

thinks.

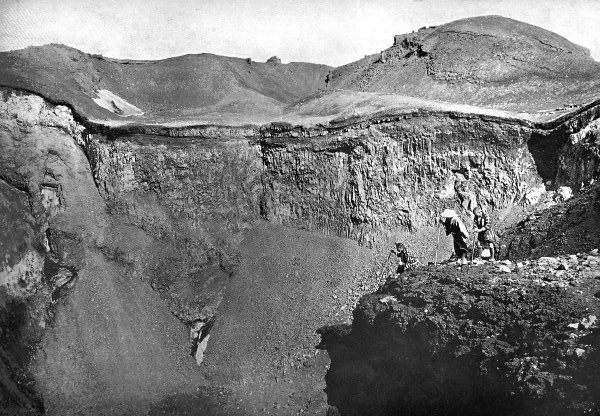

THE HOLY CRATER OF FUJI-SAN

I have come

to the conclusion he is on the verge of Buddha-hood, for he appears to

be practising austerity. Every one else in the hut is covered

up with

futons, but

he sits right in front of the open door, through which the

icy fog is sweeping. There he squats, with the full force of the

back-draughts of the wind blowing on him, and sometimes I, who am at

the farthest end of the room, shivering in my overcoat and thick

futons, can

scarcely see him for mist. He is surely attaining much

store of merit. His gaze is riveted, hour after hour, on the swirling

clouds; but he moves only to fill his pipe, and light it, and tap out

the ashes, and then begin the process over again. Smoking appears to be

his only vice. A man who can sit in his ordinary clothes in a

temperature like this must be impervious to the elements, and dead to

all carnal desires of the flesh. The marvel to me is that he even

smokes. He should certainly renounce the habit. Then he would doubtless

attain Nirvana.

Three times he has relieved the monotony

of his penance—I suppose it must be a penance—by taking a piece of

paper and doing some figuring. I begin to suspect his meditations may

be baser than I thought. Perhaps he is cogitating how much of a bill I

will stand to compensate him for the loss of patronage of transient

callers, who, in fine weather, would drop in continually, night and

day. The arrival of a foreigner, with a Japanese and four gōriki, must

have been a very opportune incident for him, as otherwise his hut would

have been all but deserted. He has a servant to assist him in the

duties of the household. The servant's office chiefly consists in

attending to the fires, which need almost constant watchfulness to keep

them going—a curious effect of the rarefied air. Thus the dreary,

dismal day passes, the storm all the while steadily abating. As night

approaches, the winds have almost ceased. For the third time I make up

my bed, and inter myself in futons,

evil-smelling oil-paper, and Keating's.

August

5.—For the third time I wake up with a racking headache. The

storm has completely subsided, but a cold drizzling rain is falling,

and chilly mists enshroud the mountain-top. Towards noon the weather

brightens, and. later the clouds begin to break. At two o'clock—oh,

joyous sight—a ray of sunshine makes the wet rocks sparkle, and a great

tinkling of bells announces the arrival of a band of some thirty

pilgrims, all in white, with dangling saké

bottles at their girdles.

They have been immured for two days in the huts on the Subashiri side,

and are now making the circuit of the crater.

I started

out for a walk round the crater's lip, and met an old and wrinkled

woman slowly making her way amongst the ruthless clinkers. After

exchanging greetings with me, the O

Bā San (grandmother) told me she

was over seventy years of age, and had taken seven days to climb the

mountain. Like us, she had been a prisoner during the last two days'

storm, but had experienced no ill effects. She had been on pilgrimages

to many of the Holy Places of Japan, but this was her first ascent of

Fuji. Like all Japanese country people, she was respectful and gentle

of speech. She had started with a band of comrades, but she had been

unable to keep up with them, and they went ahead, leaving her to make

the ascent by easy stages alone. She had met them coming down four days

before she reached the top. As we parted I noticed that,

notwithstanding her age, which for a Japanese was great, she went her

way slowly, but with steady, unfaltering steps, nothing daunted by the

trials she had undergone, and unshaken in her resolution to accomplish

the mission on which she had set her heart, unless death met her on the

road.

There

was something infinitely pathetic about that lone, aged figure, slowly

and tediously wending her way amongst the cruel crags; and I sent one

of my gōriki

to assist her, and see her safely round the crater and to

the various points that it was her desire to visit. This incident gave

me food for reflection for some time, and often afterwards. Truly that

wrinkled body was but the earthly covering of a noble, indomitable

soul. She had undertaken this arduous journey for a devout purpose—to

lay up for herself greater store of merit with the gods—and I thought

of other religions, and the women of other lands, where the Japanese

are looked upon as heathens, and I wondered how many of those other

women, with but half the old woman's measure of years, would embark on

such a task for such an object.

August

5, 3 P.M.—The

mountain-top is now quite clear, and appears to float in a sea of

clouds which are driving past a thousand feet below the summit. This

gives rise to a curious illusion—that it is the mountain which is

moving, whilst the clouds are still. We seem to be on an island forging

through an ocean of foam. It is a most beautiful hallucination, but

makes me dizzy as I watch it.

The summit of Fuji, which

looks so flat and smooth from the plains below, is covered with

enormous crags burnt to every colour of the spectrum. In places great

cliffs of slag tower a hundred feet or more above the crater's lip, and

completely encircle the great pit, which is five hundred feet or more

in depth, and about a third of a mile across. There are two separate

craters—a smaller one beside the large one—but the wall between them is

broken down. Both are choked with the detritus which is constantly

falling from the walls, and one may walk at will over the entire crater

floor. On the south and west sides, where the crater is sheltered by

the surrounding peaks of slag from the sun, there is a

snow glissade to the crater bottom; this is the only semblance to a

glacier that Fuji can boast.

Not only is Fuji sacred,

but it is the most venerated of many sacred peaks in Japan. At the

crater's eastern lip, near the rest-hut, there is a Shinto shrine

(consecrated to the worship of Sengen Sama, otherwise known as

Kono-hana-sakuya-himé-no-mikoto—"the Princess who makes the

Flowers of

the Trees to Blossom"), which ranks high among the holiest of Holy

Places of the Empire. There are several other shrines, and the great

pit is a gigantic shrine itself. As we stood on the brink of its

direful precipices a band of enthusiasts, intent on consummating what

they had come so far to do, had descended to the bottom of the abyss,

and were making a myriad echoes awake as they clapped their hands to

invoke the attention of the deity, and chanted their orisons to the

kaleidoscopic walls. On the verge of the steep, near by, others were

making their supplications with equal manifestations of zeal to the

yawning gulf before them, and the whole mountain-top was ringing with

the clapping of hands and prayer.

On making a

contribution to the shrine, which was at once recorded in a book, I was

presented with a leaflet in English, making an appeal which during the

last few years had met with such hearty response that the rest-house in

which I had been confined had, at considerable expense, been put in

thorough repair. There is still much work that might be done, however,

for the better housing of pilgrims on the Subashiri side. Therefore,

for the benefit of those who may be interested, I append a copy of the

appeal:—

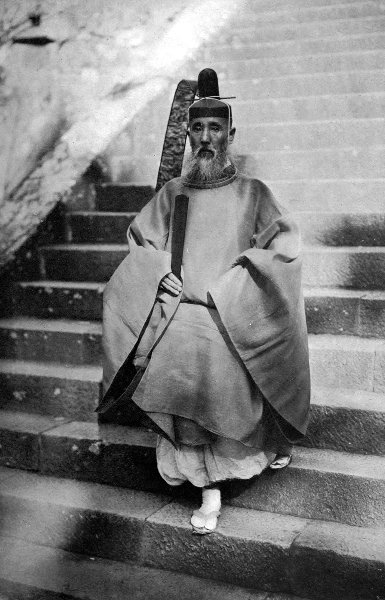

A SHINTO PRIEST

THE SHRINE ON MOUNT FUJI

Dear Sir, or Madam—On the top of Mount Fuji, whose snowy cap

kisses

the sky, stands a shrine dedicated to a Goddess known as the

Konohana-sakuyahime-no-mikoto, by whose virtue the Empire of Japan had

flourished under the sovereignty of an Empress more than once.

Prayers have been, and are being,

offered to the Goddess by loyal

Japanese, from the Sovereigns down to the people, for the furtherance

of peace and prosperity of the State.

The shrine has been raised to the

highest rank of "Kwampei Taisha" by the Meiji Government.

It is, however, a pity that not only the

shrine but also the cottage

for pilgrims (Sanro-shitsu) on the sacred mountain have decayed, so

much so that fears are entertained that they will be lost ere long, if

they are left as they are, and yet no one has ever attempted to

undertake the repair of these structures, to the great shame of the

country.

The undersigned, having obtained the

support of

influential persons in both official and non-official circles, have

resolved to undertake the work by means of subscriptions, which will be

thankfully acknowledged by

The Fuji Upper Shrine and

Cottages

Repairing Association,

c/o The "Kanpei Taisha" Sengen Shrine,

Omiya-machi, Fuji District, Shizuoka Prefecture.

Shortly before sunset I went

alone to Ken-ga-miné, the highest point of

Fuji, on its western side. Here there is a little stone hut clinging to

the edge of the mountain, which, on this side, is so steep that a mass

of lava, that I managed to urge over the edge, struck the ground but

twice, and then, with a great bound, leapt far out into the sea of

clouds and disappeared. This hut stands in mute evidence of the risks

men, and women too, are prepared to take in the interests of science.

It was built for the reception of a Japanese meteorologist

named Nonaka, and his wife, who essayed to spend the winter of

1895-1896 in it, for the purpose of making scientific observations. The

couple took up their abode here in September, but before Christmas,

owing to the terrific weather which prevailed that winter,

apprehensions were felt for their safety, and a relief expedition was

organised to reach them and bring them down. Notwithstanding the

severity of the weather, and the great difficulty of ascending the peak

when covered with snow and ice, the expedition was successful, and

reached the hut in safety. Nonaka and his wife were found in a dying

state, nearly frozen to death. It is said that they both refused to

leave, preferring death to failure in their effbrt. Their entreaties to

be allowed to die on the mountain were, of course, disregarded, and

they were carried down. For many days afterwards their lives were

despaired of, but they ultimately recovered.

As I stood

near this hut, on the utmost pinnacle of Japan, the cloudland sea was

rising slowly higher—borne upwards in heaving billows by some

undercurrent, stronger than the wind above, which was filling the

crater behind me with scudding wrack. My pinnacle was soon surrounded

to my feet and no other part of the mountain was visible. I stood alone

on a tiny island of rock in that infinite ocean, the only human being

in the universe, and soon the illusion of being carried rapidly along

in the cloud sea was so real that I had to sit, for fear of falling

with dizziness.

When the sun sank to the level of the

surging vapours, flooding their waves and hollows with ever-changing

contrasts of light and shade, the scene was of indescribable beauty.

Never in any part of the world have I seen a spectacle so replete with

awesome majesty as the sunset I witnessed that evening from the topmost

cubic foot of Fuji. A few moments only the glory lasted. Then the sun

sank into the cloudland ocean, the snowy billows turned leaden grey,

and darkness immediately began to fall.

As the last

spark of the orb of day disappeared into the foaming breakers there was

a rush of wind across the crater, due to the instant change in

temperature, and in a moment the mountain-top was in a tumult. The

great abyss became a cauldron of boiling mists, and icy blasts moaned

and whistled among the crags which loomed like ominous moving phantoms

in the turbulent vapours and dying light. It was a wondrous, almost

preternatural spectacle, like a vision of Dante's dream. I was Dante,

and the gaping crater before me was the steaming mouth of the

bottomless pit of hell.

Riveted to the spot with

bewilderment and awe, I did not realise my predicament till the mists

suddenly enveloped me. Then conviction flashed upon me that I was

nearly a mile from the rest-hut, and had not the remotest idea which

way to turn. Groping my way among the rocks, I soon found the well-worn

path, made by the pilgrims, which encircles the mountain-top; and

following it, by feeling with my stick, as a blind man finds his way, I

soon brought up against the wall of Nonaka's hut. This gave me my

bearings, and I started off in the opposite direction; but it was slow

work, and several times I lost the trail. Soon the darkness baffled me

; everything became so black that I was unable to see my hand a foot

from my eyes, and, losing the trail again, I found myself on the brink

of a precipice. A stone that I pushed over, to test the height, took

three seconds to reach the bottom, showing that it must have been about

a hundred feet high. I could go neither backwards nor forwards, as to

do so was to run the risk of falling into the crater or over some cliff

at the mountain's edge.

To any one who has never experienced a

sunset from above the clouds it

may seem almost incredible that darkness can fall so rapidly. Yet such

was the fact, for not only had the source of light disappeared below a

belt of dense vapour, some thousands of feet thick, but the belt had

now risen far above me as well; thus all reflected light from the sky

was cut off too. In less than an hour after the sun had set the night

about me was absolute.

For a long time I shouted as loud

as I could, hoping some one in the rest-hut would hear me, and at last

I heard an answering shout from one of my gōriki, who, becoming alarmed

at my long absence, had come out to look for me. Without a light I

dared not move a foot, and with the enforced inaction I was chilled

through, and my teeth were chattering with cold as I crouched under a

rock for shelter.

I waited nearly an hour more after

hearing the first answering shout. It seems that the man, being unable

to locate my calls, started off in the opposite direction, for in heavy

fog all sounds are very misleading. Finally, guided by my yells, he

reached me, but the cloud was so dense that it was not until he was

within a few yards of me that I saw the welcome penumbra cast by his

lantern on the mist.

I had had no wish to be a sacrifice

on Sengen Sama's altar, and when I was once more deep in warm rugs and

futons in

the rest-hut it seemed a veritable paradise of comfort after

the chilly experience I had just been through.

August

6.—What was my joy when one of the gōriki

awoke me, bidding me get up

quickly, as it was clear weather and an hour before sunrise! We soon

had a hasty breakfast, and I write these lines on the eastern side of

the mountain's edge, where we have come to witness the most glorious

pageantry of colour that the heavens and all the powers therein can

show.

SUNSET FROM THE SUMMIT OF FUJI

A number of pilgrims are

waiting to salute the sun. The blue-black

heavens are turning grey and the quivering stars are dimmed. The grey

becomes a more beautiful grey, soft and opalescent—like pearl. A timid

blush comes over the pearl, rose-tinting it. The blush suffuses slowly

into delicate pink. The pink deepens and becomes momentarily more

vivid, flushing the whole arch of heaven, and great shafts of gold

radiate from the east to the zenith and the poles. The clouds, which

lie close-wrapped about the earth below, are a fiery sea, with purple

shadows, and waves whose crests change from silver to scarlet and

vermilion, and then the whole slowly metamorphoses into a crucible of

molten gold. It is a spectacle of sublime beauty and magnificence.

Breathlessly and with throbbing hearts

the pilgrims drink in the

glorious phenomena of this climax of their lives. They will tell of it

to their children, and their children's children, and their names will

ever be deeper reverenced for the Mecca they have seen. The skies have

gone through every colour of the prism. Suddenly a spark, a flame, and

then a dazzling burst of fire; and lo and behold, the rosy morning is

awake once more on Fuji's pearly crest, whilst Japan below is yet

enveloped in the filmy mists of night. The pilgrims bow their heads to

the ground in adoration, and, with much rubbing of rosaries, the

plaintive cadence of their prayers rises, like a lamentation, to the

heavens above.

At Benares, the sacred city of India, as

the sun rises each morning across the holy Ganges, the prayers of the

multitude, assembled on the ghauts and bathing in the river, are as the

roaring of the sea. But even this—one of the greatest and most stirring

religious spectacles of the world—is not more picturesque than that

little band

of pilgrims, 'twixt heaven and earth, high up in the blue profound, on

the very top of Japan, kneeling in praise before the great orb that is

the emblem of their Empire. In truth, never to have seen sunrise from

the summit of Fuji-san is never to have really seen Japan.

As the morning grows, the clouds, lying shroudlike over the earth,

dissemble into little cotton-tufts once more. Amongst them blue lakes

appear. Yamanaka, nearest of them all—two miles below us, and fifteen

miles away, as an arrow speeds its flight—mirrors the azure heavens

and the clouds that float above it; whilst into Kawaguchi's limpid

depths—whose placid beauty one has but to see to love—the surrounding

mountains gaze, enamoured of the beauteous scenes reflected there. The

panorama on every side is exquisite. Japan lies below us, like a huge

map in relief. Great mountains are but mole-hills, and ranges arc mere

ridges, over which we can look, and every range beyond them, to the

horizon, which, from this altitude, seems half way up the sky. The

waters of Suruga Bay are bordered with a line of white—heavy breakers,

the pursuers of the recent storm. As we circle round the mountain's

vertex other lakes come into view: Nishi-no-umi, Shōji, and Motosu,

most enchanting lake in all the land; and then the earth is riven by

the flashing Fujikawa speeding onward to the sea, divided at its mouth

into a delta of many streams. The forests clothing the lower slopes are

sun-kissed lawns, but seamed with many a wrinkle—great gullies torn by

the torrents of water which the mountain sheds in the heavy summer

rains. Fifty miles westwards the slumbering giants of Shinshu, forming