CHAPTER I

TOKYO BAY

From the time we left San

Francisco's fine harbour behind us, few had

been the daylight hours when the heavens were not mirrored in the

ocean. The sun sank each evening in a cloudless sky ahead of us, only

to reappear next morning in a cloudless sky astern, and each successive

day had been but a repetition of the lovely day preceding it. It was a

record voyage for weather. No one on board could remember the like. The

end of it came at last, however, as it does to all good things; but to

the final hour of the voyage the kindly fate that had befriended us

never deserted us, and the last evening was even more beautiful than

all the others had been, for the moon was full, the night as lovely as

a night at sea can be, and the very air seemed laden with the spirit of

the land of our dreams that would soon be a dream no more.

I was up next morning long ere the first

streaks of dawn had dimmed the

brilliancy of the moonlight. We were due to anchor at Yokohama soon

after daybreak, and, as I came on deck, soft, balmy breezes, borne of

our rapid progress, whispered gently in my ears, and bore on their

wings the scent of land. I went up into the bow, and saw that as the

sharp prow parted the glassy waters which mirrored the starry heavens,

thin feathers of spray leaped high along the vessel's trim and tapering

sides, and burned with a ghostly light which

spread around the ship, so that she seemed to be moving in a sea of

fire. Seldom have I seen the ocean so phosphorescent in any part of the

world.

We were steaming just off the entrance

to Tokyo

Bay, and now and then a junk, or some smaller fishing-boat, loomed

suddenly out of the night, drifted like a phantom across the silvery

path of the moonlight, and passed as suddenly again into the dusky

shadows. As the day began to break, these craft increased in number and

distinctness until a vast fleet of many hundreds of them could be seen,

homeward-bound from the work of the night. The great sails of the junks

hung listlessly in a hundred tiny festoons that threw soft shadows on

the white, and the smaller boats, the sampans—with the

half-nude

figures of the fishermen swinging to and fro against the background of

the moonlit water, as they worked the long sweeps, called yulos—formed

a novel and delightful picture that filled me with anticipation of what

was yet to come.

Whilst my attention was absorbed with

the fishing-boats the morning rapidly grew, and now the delicate

outline of that loveliest of all mountains of the earth—that wondrous

inspiration of Japanese art, Fuji-san—was softly painted on the

western skies.

The grey of dawn was shot with pink, and

blue, and amber, and high in the iridescent azure, far above the

night-mists clinging to the land, the virgin cone of Fuji hung from the

vault of heaven.

Then among the blushes of the east

there was a flash, and the great red disc of day came slowly creeping

above the hills of Boshu, tinging the skies with a ruddy glow, and

staining all pink and rosy the snows on Fuji's crest. Over the holy

mountain the moon was setting, and innumerable junks, with idle sails,

lay becalmed on the mother-o'-pearl waters of the Bay.

Many times since then have I seen the

peerless Fuji. Under every

condition of sunshine, storm, and snow; and at every hour from dawn

till sunset, in spring, summer, autumn, and winter have I gazed at it

from a score of places within twenty miles of its base, but never did

the great sacred mountain appear lovelier than during that first hour I

spent in Japanese waters.

So this was Japan! My fondest

dreams had created no such scenes as these by which to form my first

impressions, and from that day it has always seemed to me that if the

fitness of things could be more strikingly exemplified than in the

adoption by the Japanese of the red disc of the rising sun as the

emblem of their empire, it would be in their having the outline of Fuji

on their flag instead.

Twice since this, my first visit,

I have entered Tokyo Bay in drizzling rain, and had I not known what

there was behind the mists, I should have had but a doleful idea of my

dreamland. Japan is a wet country in the spring-time, and Fuji so

jealous of her charms that she sometimes sulks for weeks together in

impenetrable banks of clouds. Those, therefore, who arrive when the sun

is shining, and Fuji is in complaisant mood, may deem themselves

favoured of the gods—at least the Japanese gods—and should be thankful

for the honour.

CHAPTER II

THE TEMPLES OF KYOTO

In no other part of Japan have

Nature and Art combined to scatter their

favours with such a lavish hand, within a small area, as in the old

capital, Kyoto, and its neighbouring hills and valleys. After years of

travel in many lands, I look back upon Kyoto as one of the most

beautiful and fascinating cities I have seen.

Many are

the happy weeks I have spent in roaming amongst its grey old temples;

exploring the surrounding woods; rambling over the hills that half

encircle the old city; searching its innumerable pottery-and

curio-shops; shooting the rapids of the lovely Katsura river;

visiting the homes of famous artist-craftsmen; viewing seas of

cherry-blossoms or gorgeously coloured maple-trees, and in a hundred

other ways storing up memories that have left this enchanting old city

dearer than any other to my heart.

Many a time, too, I

have seen old-time religious and feudal processions pass along its

quaint old-fashioned streets, taking one back in spirit to the days,

not half a century gone, when Japan had as yet made no endeavour to

fall in line with even the least of the Powers of the world.

My first impressions of Kyoto, however,

were not reassuring, for the

station is in an uninteresting part of the town, and the houses seemed

devoid of interest as I passed them on the way to the Miyako

Hotel.

GREETINGS IN THE TEMPLE GROUNDS

But

as my kurumaya *1 drew me further along, the feeling of disappointment

gave way to interest, and then to pleasure, as he entered a street in

which every house seemed to be a curio-shop, and where the crowd was so

thick that he could scarcely make his way. A great matsuri was being

held—the festival of a near-by temple. Hundreds of stalls lined the

thoroughfare for the sale of every kind of article, and dozens of

vendors had not set up stalls at all, but merely laid their wares upon

the ground.

The street blazed with the light of

innumerable paper lanterns and oil lamps; and by their coloured glare

I could see silks, pottery, bronzes, brasses, beautiful boxes, and a

thousand other dainty things and curios peeping out from a perfect

forest of dwarf trees. There were tiny maples, and pines, and

wistarias, and peach and plum-trees, and many others; but the bulk of

these Lilliputian arboreal wonders were cherry-trees, whose branches,

pink with blossoms, drooped over the pots, in which the trunks from

which they sprang were gnarled and grizzled as veterans of the orchard,

and, though scarcely a foot in height, were often more than twoscore

years of age. Among this pretty scene of lanterns and flowers the gay

kimono of

many a geisha

was a dash of colour in the crowd, and the

whole street was full of holiday-makers, seemingly without a trouble in

the world.

It is characteristic of the gentleness

of the

nation that all these dainty, delicate things could be displayed by the

owners in the open street, and even on the ground, amongst a throng of

people and passing vehicles. One shudders to think what might be the

result if such confidence should ever be reposed in one's

fellow-creatures in England.

I learnt later, too, that my kurumaya,

spotting me as a new visitor,

had specially gone a little out of his way, and

sought that crowded street for the sole purpose of giving a new-comer

the pleasure of a pretty spectacle. Think of a London cabman showing

such nice regard for the enjoyment of his fare! Innumerable little

kindnesses and acts of thoughtfulness like this, during my three years

of travel in Japan, come back to mind; and especially have the many

courteous acts of Mr. Hamaguchi, the clever manager of the Miyako

Hotel, helped to deepen my affection for the old capital. Many of my

most delightful experiences were due to his suggestion, and on more

than one occasion I made excursions as his guest.

The

Miyako, the most rambling hotel in Kyoto, is situated high on the

slopes of Higashiyama, "the Eastern Mountain," and a lovely panorama

lies before it. Far below are the tiled roofs of the city. It is the

Awata district, one of the most famous centres of the world for

high-class pottery and enamel. To the south, standing out in brilliant

red amidst the grey house-tops, are the main gate and wing turrets of

Tai-kyoku-den—most modern of Japanese temples. Directly in front

there is a thickly-wooded hill, with the beautiful buildings of the

ancient Kurodani monastery peeping between the pines; and northwards,

Nanzenji temple struggles to show itself from the dense foliage

surrounding it.

All round the valley there are

forest-clad hills, and as the sun sets over Arashiyama, "the Storm

Mountain,"—the beauty of which has been sung by poets for ages—the deep

note of a mighty bell breaks on the air. It is the voice of the Chio-in

temple giant proclaiming to all that the sun has run its course, and

that the day is done. Softly for a moment the vibrations tremble, and

then come swelling out in volume through the trees. Quivering waves of

sound go surging over the town, and the hills catch up the booming note

and throw it to each

other, until valley and mountain are all throbbing and echoing with the

sound. It seems to come from everywhere. It is in the air above and in

the earth beneath, and a full minute or more lapses ere the undulations

tremble away to silence, seeming to bear a message to all corners of

the land from the ponderous lip of bronze.

This bell is

one of the largest in the world, and hangs in a belfry in the grounds

of the Chio-in temple, a grand old monastery of the Jodo Buddhists on

Higashiyama. The broad and spacious approaches of the temple are

gravelled avenues, with pine and cherry-trees spreading their branches

wide overhead; and a vast terrace lies in front, from which a flight

of stone steps leads to the great two-storied entrance gate—one of the

finest in Japan. It is a typical piece of the purest old Buddhist

architecture, over eighty feet in height, with beams, ceilings,

cornices, and cross-beams all deeply carved with dragons and mythical

creatures, and decorated with arabesques in colours. Again, long

flights of steps lead higher up the wooded hillsides to the plateau

where the temple buildings stand.

As the top is reached

great flowing lines appear—the splendid curves of heavily-tiled roofs,

sweeping upwards far above the massive pillars that support them, and

the surrounding tree-tops. Great halls and little halls and pavilions

are scattered everywhere. At the threshold of the main building streams

of pure water flow over the scalloped edge of a Brobdignagian

lotus-bloom of bronze into a granite trough, at which the worshippers

cleanse all impurities from their lips and fingers before entering the

sanctuary. Inside the massive doorway a priest sits all day long, from

dawn till dark, and from dark till dawn, mechanically tapping a drum;

and every few hours the automaton is relieved and another takes his

place. These drum-tappers are very

old, with heads as innocent of hair as the parchment of the drum they

beat.

A forest of pillars, polished like

bronze, lose

their tops among the massive rafters, and the chancel is all aglow with

gold and rich embroidery. During the hours of Mass a hundred Buddhist

priests, clad in gorgeous flowing robes of silk and rich brocades of

every colour and shade, file in and settle on the padded mats before

their lacquered sutra-boxes.

Gong-beats punctuate their chants, and

incense fills the air as the smoke curls upwards from the altar

censers, and the whole scene is of bewildering beauty—a kaleidoscope of

colour.

Chio-in's fine old buildings are rich in

works

of art. Iémitsu, most peace-loving of the Shoguns, built the

priests'

apartments; and the sliding screens that form the walls arc

embellished with masterpieces from the brushes of many famous artists

of the Kano school. Among the best examples are the fusuma, or sliding

doors, of a little room of eight mats, decorated by Naonobu with plum

and bamboo branches. In the next room Nobumasa painted some sparrows so

lifelike that they took wing, leaving only a faint impression behind;

and a pair of doors, painted with pine-trees by Tan-yu, were such

faithful reflections of nature that resin exuded from their trunks.

A curious feature of Chio-in is the

floors of its verandahs and

corridors. They are made of keyaki

wood, the boards being loosely

nailed down, so that, as one walks over them, they move slightly, and

in rubbing against each other emit a gentle creaking noise. The sound

is very pleasing, and so soft and musical as to suggest the twittering

of birds. These floors are called by this most poetical of people

uguisu-bari

or "nightingale floors," and they certainly add most wonderfully to

the fascination of the temple.

THE GREAT BELL AT CHIO-IN TEMPLE

A pavilion in the courtyard

contains the great bell. It was cast in

1633, is ten feet eight inches high, with a diameter of nine feet, and

weighs seventy-four tons. For exactly a century this monster

sound-maker was peerless among the bells of the world, till in 1733 the

"Czar Korokol," the "Great Bell of Moscow," was cast. This latter,

however, is said never to have been hung, and stands in the Kremlin

grounds useless, with a large piece broken from its side—a disaster

which occurred in a fire a few years after it was made, and not, as is

generally supposed, during the burning of Moscow by Napoleon. The

Chio-in bell can now only claim second place among Japanese bells, as

in 1903 a bell was cast at the Tennoji temple at Osaka which weighs

over two hundred tons; it is twenty-four feet high and sixteen feet in

diameter.

Others of the great bells of the world are

that at the Daibutsu Temple in Kyoto, which is fourteen feet high and

weighs sixty-three tons; and the bell at Nara, a dozen miles away, is

thirteen feet and six inches high and weighs thirty-seven tons. The

"Great Bell of Mingoon," Burma, is conical-shaped, twelve feet high,

and

sixteen feet in diameter at the lip. It is said to weigh eighty tons,

but the impression I gained was that this was an exaggeration. The next

in order are the Ta-chung-tsu bell at Peking, which hangs in a temple

outside the Tartar Wall, and another of equal size which is suspended

in the Bell Tower in the centre of the Tartar City. These bells are two

out of five—each eighteen feet high and ten feet in diameter—which

were cast about the year 1420, by order of the Emperor Yung Loh. They

are said to weigh one hundred and twenty thousand pounds each (about

fifty-three tons). Two of the remaining bells are in other temples near

Peking, while the fifth is at the Imperial Palace. Another

monster which holds a foremost place among the bells of the world hangs

in a pavilion in the centre of the city of Seoul, the capital of Korea.

These oriental bells are never sounded by a tongue, but by means of a

suspended tree-trunk, which is swung and brought sharply into contact

with the lip.

The sounding of Chio-in's great basso is

accompanied by much picturesque ceremony. The chains that hold the

heavy log are unlocked, and a gang of some dozen coolies take hold of

the hand-ropes hanging from the suspended beam, and commence a chant in

unison as they set it a-swinging. When a certain line is reached they

strain upon the ropes, and bring the bole against the chrysanthemum

crest on the bell with all the strength that they can muster. A muffled

roar springs from the monster as the burred edge of this battering ram

opens its lips, but the roar quickly turns to soft, musical

reverberations that go singing over the city, and slowly purr away to

silence. The beam is checked ere it can strike again from the rebound,

and the chant continues for some minutes before another note is sent

booming and echoing into the hills and dales.

Higashiyama is the site of many other

beautiful temples. Its slopes are

densely wooded with pine and maple-trees, and in spring-time the green

of the forests is everywhere the ground-work for an embroidery of

cherry-blossoms. From these lovely woods at least a dozen temples peep.

Chio-in is the grandest, and Kiyomizu-dera the most picturesque.

To Kiyomizu one must pass along

Gojo-zaka, a narrow street that is a

perfect bazaar of toy and pottery shops, and shops whose whole fronts

are curtained with long strings of dangling saké-bottles,

made from

gourds; and there are curio and woodwork shops, and shops where only

knives and blades are sold. One may purchase here a

cherry walking-stick, with a blade concealed in it that will cut

through half a dozen copper coins without dulling its edge, and the old

shopman, the very prototype of Hokusai's sketches, will apply the test

before he accepts the small sum he courteously demands. Gojo-zaka is

the centre of the porcelain-maker's art. At Seifu's, Nishida's,

Kanzan's, or a dozen other shops, one may see exquisite specimens of

the beautiful blue-and-white porcelain of Kyoto, known as Kiyomizu

ware, offered at prices so wholly inadequate for the art with which

they are embellished, that few visitors passing along this street ever

reach the temple till long after the hour they have arranged.

Through this fascinating bazaar the

stream of humanity to the popular

old temple ceases only through the still night-hours, and the ancient

capital offers few better opportunities for leisurely studying human

nature than on this interesting street.

The hillside is

very steep, so steep indeed that many of the buildings of the

sanctuary—so ancient that its origin is lost in legend—do not rest on

the ground, but are supported on a scaffolding of massive beams and

piles. Amongst its halls and colonnades, turreted pavilions and

pagodas, one can find fresh beauty at every visit; and each balcony

discloses new and lovelier vistas of the "City of Artists" below.

The temple is one of the "Thirty-Three Places" (Saikoku

San-ju-san-Sho) sacred to Kwannon, Goddess of Mercy, in the provinces

near Kyoto. These are all carefully numbered, and Kiyomizu is the

sixteenth on the list. The shrine of the goddess is opened but once in

thirty-three years, so the chances are somewhat against the casual

visitor having the privilege of seeing the deity. Her "Twenty-Eight

Followers," personifying the twenty-eight constellations known to the

ancient astronomers of the East, stand on either side of the shrine;

and at each end of the daïs are two of the four "Heavenly

Kings," or

Shi-Tenno, who guard the world against attacks of evil. They are Tamon,

Komoku, Jikoku, and Zocho, and they defend respectively the North,

South, East, and West.

One of the lesser sights of

Kiyomizu, but a truly pathetic one, is a shrine to Jizo—the guardian

god of little Japanese children. It is a mere shed containing some

hundred stone images decked with babies' bibs—relics of their little

dead which mothers bring as offerings. Women are always to be seen

before this shrine praying earnestly for the souls of their little

ones. It is a sad, depressing spot, and I always turned away from it

heavy-hearted at the spectacle of those poor bereaved mothers and their

silent grief.

Outside of the hondo,

or main

temple,

there is a dilapidated old idol sitting on a stool. He is a queer old

fellow, with features defaced and almost obliterated with much rubbing.

His name is Binzuru, and his history is quite interesting, for he is a

deity with a "past." He was originally one of the Ju-roku-Rakan, or

"Sixteen Disciples of Buddha," and had the power to relieve all the

ills

of the flesh. The mantle of his holy state, however, did not, it seems,

subdue his human nature; for one day he gave his nearest companion a

dig in the ribs and remarked on the beauty of a woman passing by. For

this imprudence the susceptible old saint was expelled from the

fraternity, and thus it is that his image is always seen outside the

sanctum, whilst his brother disciples are placed inside it. He is,

however, exceedingly popular with the lower classes, who believe that

by rubbing any portion of his image they will obtain relief from

ailments afflicting the corresponding portion of their own persons.

Hence his face and limbs are polished smooth, and almost worn away in

places by centuries of this gentle friction.

NOOMLIGHT AT KIYOMIZU-DERA

Many an evening did I go to the

old temple at sunset to admire the

beauty of the view. The flaming vermilion pillars and sweeping eaves of

the main gate frame a lovely picture at that hour. A long flight of

granite steps leads to the street of dangling saké-hottles,

which in

turn leads straight to the old Yasaka pagoda, standing like some grey

old guardian spirit watching over the town below. Here and there, among

the houses of the city, the great curved roof of some Buddhist temple

looms gigantic in the evening haze; and westwards over the "Storm

Mountain" the sun sinks in a blaze of yellow glory, which turns the

pillars and turrets of venerable Kiyomizu into some wondrous fairy

fable.

But Kiyomizu by moonlight is lovelier

still. Once

I prevailed upon a Japanese friend and his little daughter to accompany

me to the temple when the moon was full. The Japanese do not like such

places at night, for among this highly imaginative and superstitious

people belief in the supernatural is universal; and temples and other

such gloomy places are haunted by the ghosts of those who have lived in

them. A great silence, therefore, hung over the deserted buildings.

At the threshold of the second gate,

where a scowling dragon sends a

stream of silver water gushing from his brazen throat, my friend made

furtive attempts to prevail upon me to stop and admire the beauty of

the moon instead of going farther; and little O Kimi San, finding her

father's hand insufficient protection, came between us, taking mine as

well. I pressed on, however, resolved to see it all. As we entered the

dark portal, the creaking floors awoke a myriad echoes among the walls

and ceilings, and O Kimi San, walking on tiptoe with trepidation, her

little Japanese brain busy with all the

ghost and fairy-tales she knew, peered into the gloomy shadows, seeing

"spooks" in every corner and lurking goblins by every post. Old

Binzuru's leprous head looked fearful in the moonlight, and O Kimi, her

face hidden in her father's kimono,

clung to us both for safety.

In the shadowy corridors we all

involuntarily glanced back more than

once, thinking some one followed behind; no one was there, however,

the supposed follower being naught but our own footfalls reflected by

the whispering walls. At the Oku-no-in a voice rang out in challenge.

It was one of the resident priests, who, finding we were only harmless

sightseers paying a nocturnal visit to the temple, courteously oflfered

to conduct us, much to O Kimi's relief.

As we stood on

one of the verandahs, far above the trees, watching the twinkling

lights of the "City of Artists," the moon was braiding the clouds with

silver, and shedding soft radiance and fitful shades on the balustrades

and heavily-thatched gabled roofs about us. Not a sound broke "the

soft silence of the listening night'' save the gentle murmur of a

little cascade below us, and the chirruping of the crickets, until a

nightingale burst into song in a tree-top at our feet. A flood of

melody poured from the little throat, a perfect rhapsody of runs and

trills, and when it ceased another answered from a tree near by. Thus

in turn they sang, filling the old temple and the woods with glorious

music; and little O Kimi San, enraptured with this fresh experience,

clapped her hands in delight, crying, "They sing to each other! How

beautiful! Oh, how glad I am we came!"

It was a pretty climax to our ramble, and as rare as delightful, for

the uguisu

are not often heard in these parts, I believe, though I have

heard them nightly in summer at Ikao and Karuizawa.

Higashiyama's lower slopes are

labyrinths of pine avenues, paved with

broad stone flags, and all a-whispering with the streamlets that course

in deep culverts on either side. The grounds of temples and monasteries

abut each other everywhere, and one discovers some fresh carved gate or

old stairway among their shady groves at every turning. Near the Yasaka

pagoda there is one of the finest bamboo groves in Japan, where

thousands of tall, slender shoots bow to each other with every breeze,

and mingle their feathery tips full fifty feet overhead. I studied it

well before attempting to photograph it. In a high wind it cannot be

successfully done, nor in bright sunlight can its full beauty be shown.

One day, however, the sun, being very weak, gave just the light I

wanted. I hurried to the avenue, and was fortunate enough to induce

some geisha

to pose for me in their rikishas.

In order that I should

not be interrupted I told one of my kurumaya to stop at

each end of the

grove and prevent anybody from passing. Having some difficulty in

arranging the picture, a good deal of time passed, and just as I

secured it, two dapper policemen came up and demanded to know why I was

obstructing the road, and with them came some scores of people that the

zealous kurumaya

had been keeping back. My explanations were of no

avail, though they were courteously received. My name and address, and

the names of all the kurumaya

and of the girls, were with much ado

taken down, and I was notified that fines would be imposed upon all of

us. The picture, however, did not prove so very expensive as it

sounded, for when the bill for the aggregate fines was presented to me

the same evening I found it amounted to no more than six shillings.

At Higashiyama's base there is another

temple, called

San-ju-san-gen-do, the "Hall of Thirty-Three Spaces "—the spaces being

those into which it is divided by a single row of thirty-two pillars.

The place is as different from Kiyomizu as it well could be. More like

a great barn than a religious edifice, it is yet unique and very

interesting, and although not resembling it architecturally, nor

possessing any of its beauty, it yet reminded me of the "Thousand

Buddha Temple" at Peking. The two temples have one feature in common:

that at Peking boasts one thousand images of Buddha; San-ju-san-gen-do

possesses one thousand and one effigies of Kwannon, Goddess of Mercy.

These effigies are covered with smaller ones on their foreheads, halos,

and hands, until it is said the grand total of 33,333 is reached—a

statement which I accepted without attempting to verify its correctness.

They are a tawdry, motley company, these

tiers of gilded goddesses,

whose serried ranks, a hundred yards long and a full battalion strong,

fill the vast building from end to end. The images, many of which are

of great age, are continually being restored. In a workshop behind the

vast stage an old wood-carver sits, his life occupation being the

carving and mending of hands and arms, which are constantly dropping

off, like branches, from the forest of divine trunks—for Kwannon is a

many-limbed deity, and few of the images have less than a dozen arms.

Rats scuttled over the floors and hid in the host of idols as we made

our way round them; and at the back of the building we were stopped by

an old priest, who sat at the receipt of custom and demanded a

contribution from every visitor.

One day, as I suddenly

turned a corner in this temple, I saw a tourist, who supposed no one

was looking, deliberately break a hand off one of the gilded figures

and put it in his pocket.

A BAMBOO AVENUE AT KYOTO

It is strange to what acts of

vandalism the mania for collecting useless relics leads some people.

Once in Kyoto I was invited by two travellers, whom I had just met, to

come to their room, where they were busy packing, prior to leaving for

home. I noticed some beautiful specimens of hikité—inlaid ornamental

bronze plates used as finger-grips on sliding doors—lying on the floor.

I picked them up and admired them, asking where they had bought them,

as a glance showed me they were very good ones. To my amazement they

told me they had ripped them from the doors of a Japanese hotel at

which they stayed, and were now discarding them because they could "not be bothered with them any longer."

When such acts as

these are committed in a land where one is often on one's honour with

regard to some dainty work of art in the simple furnishing or

decoration of one's room, can it be wondered at that foreigners are

sometimes viewed with suspicion t It will take many years to undo the

evil left by that act in that hotel-keeper's mind. And these young

fellows were the sons of wealthy New Yorkers, and appeared to have

unlimited money to spend!

In summer Higashiyama's woods

ring with the shrill chirping of a myriad cicadas, called seimi; and

small boys, with long bamboo poles tipped with birdlime, swarm from the

town to hunt the festive insect. Many a time, as my kurumaya ran past

these seimi-hunters,

I have had to dash their bamboo points away from

my face, and have so often seen others narrowly escape injury from

these dangerous playthings, that it is not surprising to learn that

much of the blindness seen in Japan is due to the careless handling of

sticks by Japanese children.

The captured seimi

are sold for a trifling sum to an entomological

dealer, who imprisons them in tiny bamboo cages, often

most beautiful specimens of dainty and delicate workmanship, and his

wayside stall is all a-twitter with the varied cries of a score of

different insects. Their names are as numerous as their species, but

the children class all cicadas under the generic name of seimi. From

some of the little cages the intermittent lights of a dozen fireflies

flash; in others as many glow-worms shed a feeble glimmer, and the

insect-dealer's stall is always the centre of a group of admiring

children.

The sounds emitted by many of the

cicadas are

very pleasing and sweet, whilst others have a shrill metallic note that

hammers one's brain to distraction. The vibrating song of the seimi is

the signal that marks the arrival of summer. From end to end of Japan

their cries grow crescendo as the season advances, until in September

the drowsy hum of the woods becomes a fortissimo of one continuous

scream. In places they gather in prodigious numbers with one accord;

their song then becomes a veritable pandemonium, and the air quivers

with their incessant din from morning till night. From August on this

woodland music becomes a gradual diminuendo, which ceases altogether in

November.

I love the song of the seimi, and always

listened for its first lone call as in England I used to look for the

first swallow or listened for the cuckoo; only the sweet chirp of the

Japanese insect gave me infinitely greater pleasure. I love the

Japanese summer, too, and the seimi's

voice, proclaiming that summer

was at hand, always filled me with gladness. More than once, as I have

listened to the sweet little singer in the autumn, it has fallen

lifeless from the tree. To the very last the muscular power, which

enabled it to produce by friction its joyous song, had escaped the

dread disease that fed upon its vitals, and it died as it had lived, a

merry-maker

and joy-giver, happy and giving happiness to the end. The woods have

thus their tragedies to those who love them; and few could escape a

pang of sorrow at the death of so dutiful a little creature, fulfilling

to the final moment of its life the service entrusted to it by its

Creator.

And every autumn there came a day when I found

an indefinable something missing in my woodland rambles. Suddenly I

would come upon the tiny body of what was once a joyous seimi, lying in

my path. Then I knew what it was that the woodland lacked. It was the

gladsome song of summer: the chorus of the seimi, which,

whilst the

woods slowly turned from green to gold, and brown, and scarlet, had

become gradually hushed, until now every voice of that chorus was

stilled in death.

Higashiyama is the home of other, and

less pleasant, members of the insect-world. Mosquitoes, which breed in

vast swarms in the rice-fields, seek the shelter of these woods, and

make life a burden to those who have to pass the summer in them. After

dark no place is secure from this pest, and even the mosquito-curtains

over one's bed must be carefully searched each night to see that no

crafty, enterprising intruder is lurking for its victim in their folds.

Almost every Japanese temple of any

note, that is not framed by

Nature's graces, has a garden which their innate love of the beautiful,

and surpassing skill, enables the priests to make a veritable paradise

of beauty. They are past-masters not only in the art of keeping up a

garden, but of allowing it to age with dignity, and yet increase in

loveliness without replacing one single feature.

Such a garden is that at Kinkakuji, combining both natural and

artificial beauty in a manner so skilful that there is little but what

appears to be the unhampered handiwork of

nature. It is the lovely grounds, however, that foreign visitors go to

see rather than the old buildings themselves—though these contain

many-famous works of art by such old masters as Korin, Eishin, Kano

Tanyu, and many others. Most of the Kyoto temples shelter a veritable

feast of art on their walls, but there is no other temple in Japan that

can show such grounds as Kinkakuji. They have been the inspiration of

many a famous garden, though few others can equal their tranquil beauty.

The temple was built by the Shogun

Yoshimitsu—who resigned the throne

to his son Yoshimochi in 1397—as a country villa to which he could

retire from the cares of the world. He founded the adjacent monastery,

became a monk, and ended his days there.

Kinkakuji means

"Golden Pavilion," from the fact that formerly the upper story of the

building was entirely covered with gold. Traces of it still remain,

from which one may, if gifted with imagination, conjure up a vision of

its former grandeur. It still makes a beautiful picture as it stands

overlooking the lake, and is a favourite motive for artists, and for

craftsmen working in every kind of material.

As one

approaches the old pavilion a shoal of carp appear at the water's edge,

begging for some of the popped corn which the watchman sells. Whilst I

was feeding them my attention was distracted by a youthful acolyte,

whose shaven head was polished to the lustre of a billiard-ball, and

who was acting as cicerone to a party of Japanese country visitors.

They followed in single file, as the boy, in monotonous, high-pitched

tones, described the paintings on the doors and walls, and then,

leading them out into the garden, commented on each spot and stone of

note, never once lifting his eyes from the ground the while.

KINKAKUJI (THE GOLDEN PAVILION)

He had it all by rote, after the manner of his

kind, and his thoughts were obviously busy with other matters; but his

charges listened respectfully, now and again sibilantly sucking the

breath between the teeth when famous names were mentioned. Presently

one of the visitors, of a more enquiring turn of mind than the rest,

craved further information, and interrupted with a question; after

vainly trying to answer it there was much rubbing and scratching of his

bald pate before the cicerone could regain the run of his discourse.

The lake, which in summer is almost

covered with a flowering plant, is

surrounded by shady walks beneath pines and maple-trees, and little

islets and ornamental stones break up its surface. In autumn the groves

are ablaze with colour; and in winter, when the pines and temple roofs

bear, as they sometimes do, a thin coating of snow, the old garden is

more beautiful than ever.

In the monastery court there

is a wonderful example of the tree-trainer's art which has taken a

couple of centuries to produce. It is a full-grown pine representing a

junk under sail. Hull, mast, sails, and all are there, the branches

being restrained by careful trimming and training on bamboo frames,

until the result attained constitutes the most famous arboricultural

effort in Japan.

Kinkakuji stands outside the city at

its northwestern corner. Opposite it, at the north-eastern, is

Ginkakuji, whither Yoshimasa, eighth of the Ashikaga Shoguns, retired

in 1479 upon his abdication of the Shogunate. Japanese society owes

much to Yoshimasa, for during his meditations in this lovely secluded

spot, he, with Soami, the artist who designed the garden, and the

Buddhist abbots Shuko and Shinno, his favourites, "practised the

tea-ceremonies, which their patronage elevated almost to the rank of a

fine art." *2

The road to Ginkakuji lies through a

farming district of terraced

fields, which are planted out to rice as soon as the barley crop is

harvested. The roofs of half a score of grand old temples towered

amidst magnificent cryptomeria groves and bamboo coppices as we sped

through this bounteous farmland; and when at length we pulled up at

Ginkakuji's gate, a Lilliputian priest, with shaven head and polished

crown—the counterpart of the little cicerone at Kinkakuji—acted as our

guide.

He conducted us by winding paths round a

pretty

lake, over the "Bridge of the Pillar of the Immortals" that spans a

stream called the "Moon-Washing Fountain"; chanted out the story of

the "Stone of Ecstatic Contemplation"—a tiny island in the lake; and

showed us over the "Silver Pavilion"—which, it seems, never was

covered with silver at all, as its name "Ginkakuji" implies it was,

for the ex-Shogun died before he was able to accomplish his wishes with

regard to it. It has little interest beyond its picturesque appearance

and an aged image of Kwannon in the upper story.

The

little bonze

then took us into the garden again, and finally brought us

to two great conical heaps of sand. These are named the "Silver-Sand

Platform,'' and the "Mound Facing the Moon." On the former Yoshimasa,

this devoted disciple of the beautiful, "used to sit and hold

aesthetic revels." On the smaller "he used to sit and moon-gaze."

In one of the apartments of the building near by there is a statue of

Yoshimasa in priestly robes, marvellously lifelike. If it be a true

portrait of the ex-Shogun it must depict him in his fighting days, for

it resembles rather a fierce warrior in disguise than a fastidious,

moon-gazing priest.

THE PINE-TREE JUNK AT KINKAKUJI

It would be interesting to know what kind of

aesthetic revelry the monarch indulged in. If, however, the elaborate

system of etiquette, called cha

no yu, which he perfected in his

retirement here, be like his sand-heap revels, then it is easy to see

how he could have indulged in them, to his heart's content, without

disturbing the surface of his "platform," for anything more dignified

and stately than this ceremonial it would be impossible to imagine. To

Yoshimasa and his code of etiquette, so rigidly followed to this day by

the Japanese upper classes, must be largely credited that superb grace

of manner and absence of self-consciousness that enables the Japanese

lady to be the very embodiment of ease and composure in all her

actions. The inflexible code of cha

no yu, prescribing minutely her

every movement in the intricate tea-ceremony, supplies rules that

govern her deportment in every possible situation in which she is ever

likely to be placed. To any one versed in the art, lack of

self-possession under any circumstances would be impossible, and none

but the most ultra-refined of races could ever have evolved it. Though

I have many times seen its formalities performed, to attempt to

describe them with any degree of justice is beyond me. Some, even, who

have taken lessons in the art have tried, and failed. They have merely

described its forms, but left them devoid of all the poetry, and

beauty, and culture which they mirror. One must see a Japanese lady

perform the tea-ceremonial to know what it means—a foreigner can only

burlesque it either in its performance or description. *3 Japanese Buddhism is divided into six principal sects. In

order of their numerical strength they are: Zen; Shin, or

Monto, or Hongwanji; Shingon; Jodo; Nichiren; Tendai. The Shin

sect, whilst not the most numerous, raise the most imposing edifices

from the standpoint of linear proportion. Their temples are always well

in the heart of the city. Higashi Hongwanji, or Eastern Hongwanji, in

the southern part of Kyoto, is not only the largest, but one of the

newest and grandest temples in Japan.

One can find old

temples, and grand temples, and magnificent temples, and temples to

which almost any appreciative adjective might apply, in many Japanese

cities; but it is not everywhere, nor indeed anywhere else than in

Kyoto, that one can see what a Buddhist temple of truly majestic

proportions looks like when almost new. Such, however, is Higashi

Hongwanji, for it was only completed as recently as 1895, after eight

years of building—the original edifice having been destroyed by fire

during the revolutionary struggles in 1864.

At each of

the two gates in the massive fifteen-foot wall which surrounds the

courtyards, there is a pair of superb bronze lanterns, deeply carved;

and in the enclosure an immense lotus-flower of bronze serves as a

fountain, from which pure water flows for the use of worshippers before

entering to their devotions. The lotus being the sacred emblem of the

Buddhists, fountains in imitation of its blossom are to be found in

many of their temples.

Higashi Hongwanji's buildings,

for simple beauty and grandeur, are perhaps more impressive than any

others in Kyoto. The Daishi-do, or Founder's Hall, rears its colossal

roof in sweeping curves one hundred and twenty-six feet above the

ground; and ninety-six enormous boles cut from keyaki trees—the

wood

of which is so hard as to set time at defiance—support it.

The manner in which these great pillars,

and the immense pine beams

above them, were hoisted into place, is interesting as showing

something of the sound foundation on which Japanese Buddhism rests;

and that a great temple like this could rise, more magnificent than

ever, out of the ashes of its predecessor, does not seem to indicate

that the ground—into which a horde of American missionaries are

endeavouring to force the seeds of Christianity—is very soft, as some

would have us believe, but can produce little evidence to prove.

When the call for contributions went

forth, those who had money to

give, gave it; and those who had none, but yet were strong of muscle

or skilful with their hands, gave their labour to the rearing of the

great edifice. And the women, in thousands, not to be behindhand with

the men in bestowing what they could, sheared off their raven locks to

be woven into twenty-nine immense hawsers with which the ponderous

pillars and beams were hoisted into place. These cables of human

hair—the largest of which is sixteen inches in circumference, and

nearly a hundred yards in length—are preserved as relics in the temple,

as a pathetic message to the centuries yet to come of the sacrifices

that the women of Meiji could make for the creed in which they lived

and died.

Higashi Hongwanji, however, contains no

old

art treasures, as they were all destroyed when the previous buildings

were burnt. Its interest lies in its magnificent and well-balanced

proportions, and the proof it affords that the Buddhist architect of

to-day is as skilful as any of his predecessors. Not the least

interesting of its sights is the pavilion in the courtyard, which

shelters a huge bronze bell.

The Shin Buddhists have another temple, smaller, but infinitely more

interesting to the artist and lover of old-time things. This is Nishi

Hongwanji—the Western Hongwanji. Its

apartments are a veritable palace of the richest and finest of Japanese

art. Never have I trod shoeless over cold polished floors and chilly

mats more willingly and reverently than through this pageantry of

treasure. The main buildings, splendid as they are with coffered

ceilings, arabesqued cornices, golden walls, carved cedar doors and

ramma, and

gilt and painted shrines, are yet eclipsed in interest by

the sumptuous feast of art in the state apartments of the Abbot's

palace.

Here are masterpieces of the Kano, and

other

schools, on sliding screens, and doors, and walls. There are wild geese

and monkeys by Ryoku; palm-trees and horses by Hidenobu; a heron and

a willow-tree, and a sleeping cat and peonies by Ryotaku; Chinese

screens by Kano Koi; waves by Kokei; tigers by Eitoku; deer and

maple-trees by Yoshimura Ranshu; bamboos, with sparrows on a gold

ground, by Maruyama Ozui; chrysanthemums by Kaihoku Yusetsu;

wistarias by Naozané; and a whole gallery of works, by

other artists,

which would take some days to examine thoroughly.

Hidari

Jingoro, most famous of all Japanese wood-carvers, is well represented,

as he is in most temples of any note. Indeed, the short span of this

left-handed artist's days (1594-1634) must have been worthy of a more

strenuous era, estimated by the numerous works he left. One of his

carvings on the Higurashi-no-Mon, or ''Sunrise-till-Dark Gate,"

so called because a whole day and night might be spent in examining it,

represents "Kyo-yo, a hero of early Chinese legend, who, having

rejected the Emperor Yao's proposal to resign the throne to him, is

washing his ear at a waterfall to get rid of the pollution caused by

the ventilation of so preposterous an idea;

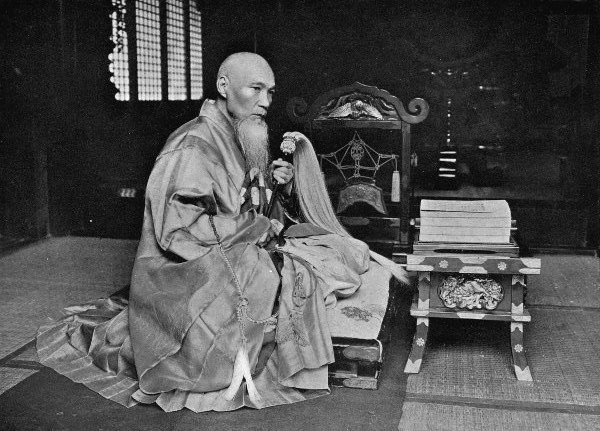

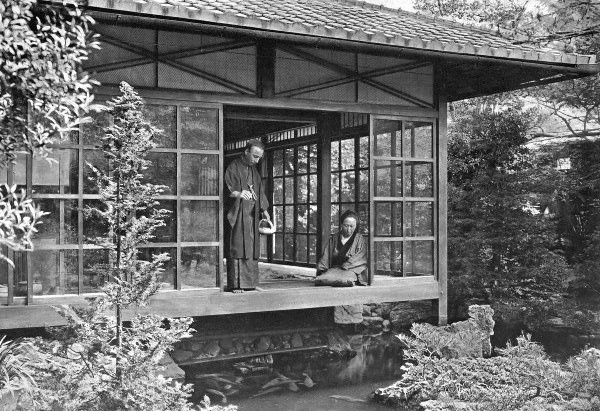

A BUDDHIST ABBOT

the owner of the

cow opposite is supposed to have quarrelled with him

for thus defiling the stream at which he was watering his beast." *4

From room to room, each more beautiful

than the one we had left, the

old bonze

led us, over singing "nightingale floors" and through many

painted doors, stopping to comment at every few steps on some famous

work of art or point of interest.

At length we were

conducted to the garden. This was one of the favourite pleasure-grounds

of Hidéyoshi, most poetical of Japanese warriors. When he

was not busy

with schemes for the conquest of Korea or the invasion of China, here

he used to come and restore his jaded body with rest, and feast his

aesthetic soul on the beauty of O Tsuki San, the Lady Moon.

The pretty winding lake was crossed with

stone and rustic bridges.

Ducks sported in the water and old stone lanterns peeped from

herbaceous thickets or maple bowers, and were reflected on the surface.

Palms, and banana-trees with elephantine leaves, gave the garden a

tropical look, and but for the temple vistas through the foliage, one

might imagine oneself in Ceylon. There was a Buddha in a shady nook,

and great red carp gleamed in the water at its foot. They followed our

movements round the pond until the old priest—standing on the bridge,

hewn from a single stone, that spanned an arm of the pool—threw them

handfuls of boiled wheat, which they fought for greedily.

In the temple courtyard there is a fine icho-tree, whose

leaves, should

a conflagration threaten danger, would immediately become fountains of

gushing water, and thus preserve the sacred edifice from harm.

Although there are no praying-wheels in any of the Kyoto temples, I

have seen several in other parts of Japan, the

finest being a pair at the great temple of Zenkoji at Nagano.

Every one has heard of the

praying-wheel, the instrument—I might say

the time-saving instrument—of devotion so popular with the Thibetan

Buddhists. And every one knows that it is a little box of prayers which

is whirled round by a handle held in the hand, the pious whirler laying

up for himself as great a store of merit each time he whirls as if he

recited the whole of the prayers with which the box is filled.

I could never look at a prayer-wheel

without being reminded of that

devout individual who, wearied with the repetition of a long list of

prayers every evening, hit upon the brilliant idea of writing them out

and hanging them at the head of his bed. Then each night he piously

went on his knees, and, indicating the list with his finger, fervently

breathed, "Them's my sentiments, O Lord. Amen." Thus did he save time

and salve his conscience.

In order to understand the

significance of the prayer-wheel it must be borne in mind that Sakya

Muni, the founder of Buddhism, who was a Hindu, when he sat for six

years in meditation under the Bo-Tree at Buddha Gaya, conceived and

afterwards established a philosophy which ultimately crystallized into

the Buddhist religion, founded on the belief, current in India at his

birth (the date of which is uncertain; it was either in the fourth or

fifth century B.C.), as it is to-day, that death does not alter the

continuity of life but merely alters its form. Death and rebirth follow

each other in constant succession. According as a man has sowed in this

life so shall he reap in the next, and so on until the final break-up

of the universe, or the attainment of Nirvana, which latter, being the

reward of a perfect life, is the hope of all good Buddhists.

The conquest of all earthly desire is

the greatest step towards the

cessation of rebirths, and it is to assist such pious wishes that the

help of the prayer-wheel is enlisted.

Although the small

whirling prayer-box of the Lama is well known, I do not think it is so

widely known that there are other forms of this devotional contrivance

; and I am quite certain there are many people who, while knowing Japan

otherwise well, are unaware that it is used in that country. About this

instrument, as used in Japan, how can I possibly do better than quote

the words of Professor B. H. Chamberlain? In Things Japanese he

says

of the praying-wheel: "This instrument of devotion, so popular in

Thibetan Buddhism, is comparatively rare in Japan, and is used in a

slightly different manner, no prayers being written on it. Its raison

d'être, so far as the Japanese are concerned,

must be sought in the

doctrine of ingwa,

according to which everything in this life is the

outcome of actions performed in a previous state of existence. For

example, a man goes blind; this results from some crime committed by

him in his last avatar. He repents in this life, and his next life will

be a happier one; or he does not repent, and he will then go from bad

to worse in successive rebirths; in other words, the doctrine is that

of evolution applied to ethics. This perpetual succession of cause and

effect resembles the turning of a wheel. So the believer turns the

praying-wheel, which thus becomes a symbol of human fate, with an

entreaty to the compassionate god Jizo to let the misfortune roll by,

the pious desire be accomplished, the evil disposition amended as

swiftly as possible. Only the Tendai and Shingon sects of Buddhists use

the praying-wheel—gosho

guruma as they call it—whence its comparative rarity in

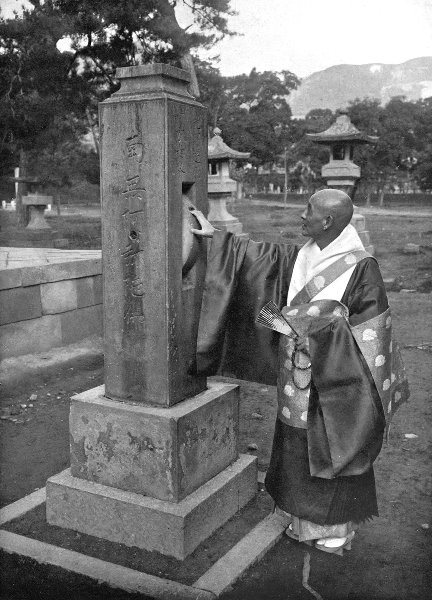

Japan."The picture shows the priest in the act of revolving the wheel.

As Chio-in, Kiyomizu, and the Hongwanji

are the principal Buddhist

temples in Kyoto, so Inari-no-Yashiro and Kitano-Tenjin are the most

important Shinto shrines.

That Inari, about two miles

from the heart of the city on the Fushimi road, should be particularly

popular with the farming classes is not surprising, seeing that its

patron deity is the Rice Goddess. There are probably more temples

raised in honour of Inari throughout Japan than to any other member of

either the Shinto or Buddhist pantheons. They number many thousands, if

one includes the wayside shrines to be seen in every rural district.

Inari's temples are distinguished by red torii, sometimes in

great

numbers, and by stone images of a pair of foxes, as popular

superstition credits the fox with being the incarnate form in which the

deity comes to earth. The fox is held in great dread in Japan, as he

has the power of entering the body of a human being and there

comforting himself much as the devils of the New Testament did before

their exorcism caused the destruction of the Gadarene swine.

Dr. Baelz of the Imperial University of

Japan is quoted by Professor

Chamberlain as follows:" Having entered a human being, sometimes

through the breast, more often through the space between the finger

nails and the flesh, the fox lives a life of its own, apart from the

proper self of the person who is harbouring him. The person possessed

hears and understands everything that the fox inside says or thinks,

and the two often engage in a loud and violent dispute, the fox

speaking in a voice altogether different from that which is natural to

the individual.

A BUDDHIST PRIEST AND PRAYING-WHEEL

The only difference between the cases of possession mentioned

in the Bible and

those observed in Japan is that here it is almost exclusively women

that are attacked—mostly women of the lower classes."

The first of Inari's many buildings

stands at the end of a

stone-flagged avenue of pine-trees entered through a great vermilion

torii.

Under the heavily-thatched eaves hangs a large polished mirror

of bronze. This device—which was borrowed from Buddhism and is repeated

in the other buildings—seems to say to all who enter "Know Thyself,"

and therein it embodies the whole teachings of the Shinto creed. Shinto

has no dogma nor moral code; it offers no sage admonitions for the

avoidance of worldly pitfalls, nor holds out, to those who

instinctively elude them, any hope of future reward. Its whole counsels

are summed up in the exhortation to its adherents to follow their

natural impulses and obey the Mikado's laws.

Shinto, or

the "Way of the Gods," is based on the assumption that, in Japan, man

is born with an instinct that teaches him to distinguish between right

and wrong, and therefore there is no need whatever for any code such as

might be necessary for the guidance of less-favoured mortals. The

mirror is its emblem, mutely exhorting its votaries to look into their

hearts and see that they are as clean as a properly-regulated instinct

should keep them.

There are no art works at Inari, or in

any other Shinto temple; simplicity is as much the key-note of its

buildings as its creed, and the magnificent elaboration, gorgeous

embellishment, and intricate ritual of the imported Indian religion

finds little echo in the indigenous faith. *5

The inevitable carved foxes

are, of course, to be found. There are

several pairs of them, covered with wire to keep the birds from

defiling them. There are some fine ishi-doro

(stone lanterns), too, and

a number of brass and bronze ones hang in the various pavilions.

Broad stone courtyards and many flights

of steps lead to a dozen

smaller shrines, and all day long the temple precincts resound with the

clapping of hands and jingling of bells, as the worshippers bring their

palms sharply together to invoke attention, and rap the call-ropes

against the hollow bronze gongs to make assurance doubly sure that the

deities are heedful, before making their supplications.

The verandah of the main building is

guarded by a pair of carved and

painted koma-inu

and ama-inu.

These very ferocious-looking creatures,

with nicely-groomed and curled manes and tails, are an idea imported

from Korea and China. They are credited with the power to ward off the

attacks of evil spirits, and are to be found in many Japanese temples.

At the Lama temple in Peking there is a

very fine pair, superbly carved

in bronze, and an immense granite pair guards the entrance to the

Palace in Seoul, Korea.

In China they represent the

Heavenly Dogs that devour the sun at the time of eclipse; the ball

often carved in the mouth of one of the pair shows the orb of day

undergoing this experience. In Japan they do not appear to mean

anything in particular, having simply been taken over from their

neighbours by the Japanese, together with the religion, as picturesque

and appropriate features. One of the pair always has its mouth open and

the other's lips are tightly closed. Opinions differ as to which is the

male and which the female, but a Japanese friend offered the

explanation that the female is always shown with the mouth open, "as it

is quite impossible for a woman to keep her mouth shut."

Inari's courtyards are the haunt of

fortune-tellers and diviners,

mendicant cripples, toy-sellers, and an old woman, who for the sum of

three sen

(three farthings) will liberate a small bird from a cage,

thereby bringing to the donor of this amount some merit for the kindly

act. For the sum of threepence one might free the whole of her stock in

trade, and when I did so, giving the old beldame double payment, she

chuckled with delight and was quite overwhelming with her benedictions.

The Japanese uranaisha, or

fortune-teller, fills a very serious and

material place in the estimation of the lower classes of the people.

They resort to him in every conceivable form of trouble. For a small

sum he barters advice to the love-lorn maiden or the unhappy wife;

instructs mothers as to the probable outcome of the ailments afflicting

their children; warns his patrons against, or gives his assent to,

proposed journeys; counsels them in business undertakings; looks into

the future for them, or lays bare the past; delineates character in

their palms and faces; advises them in matrimonial affairs; indicates

where lost articles can be found, and in a hundred ways comforts and

assists them in distress.

With a small pile of books,

and a joint of bamboo filled with his divining rods, he is to be found

at more than one temple in most cities of any size. How much reliance

may be placed on his advice and prognostications is a matter for the

individual to decide. The following cases, however, have come within my

own experience, and I offer them as of possible interest, knowing them

to be actual facts.

A friend, an Englishman many years resident in Japan, contemplating

embarking in business of a seafaring nature necessitating a long and

risky voyage in a sailing ship,

was admonished to consult a Japanese uranaisha before

accepting the

command of the vessel offered him. He did so, and was advised that the

venture would be a sound success. Acting on this advice he signed the

agreement at once and embarked on the voyage, which proved eminently

successful. Again he started off, after securing the fortune-teller's

assurance that fortune would follow him. Again he returned, happy over

a prosperous voyage. A third time he consulted the uranaisha with like

results. A fourth time he went to him; but on this occasion the old

man, after shuffling his rods and searching his books, anxiously urged

him to abandon the venture, as the luck had turned against him, and

nothing but direst misfortune would overtake him if he persisted in the

enterprise. So firm had his belief in the fortune-teller's powers

become, that he immediately sent in his resignation. In due course the

vessel, under another master, set forth again. That was many years ago,

and to this day no soul has ever heard of her. Superstition finds no

place in this friend's composition, but his faith in the powers of the

uranaisha

is unshakable. In relating this incident he said, "I have

told it to you for what it is worth. You can laugh at it or not, as you

like; but for my part I am absolutely certain that these fellows are

not humbugs, but have studied the science of divination so deeply that

it is possible for them actually to look into the future." He has

always been true to his conviction, and has never embarked in any

business venture since without first laying the whole matter before the

same fortuneteller, and he strongly advised me to consult the old

fellow too.

In November 1905 I left Japan for India, not knowing when I should

return, but telling a faithful servant I should probably be back in the

following June.

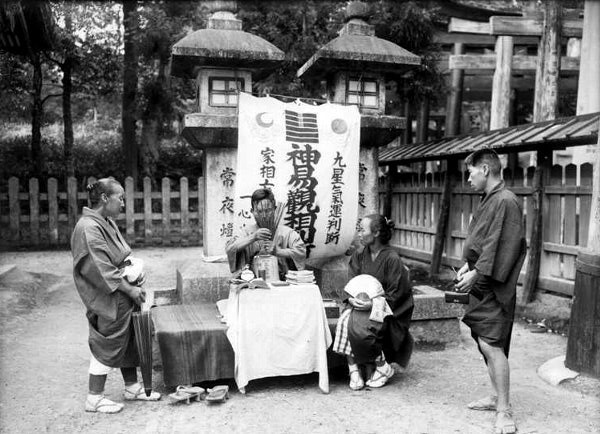

A FORTUNE-TELLER AT INARI TEMPLE

I

returned in May, arriving in Tokyo at 6 o'clock one day. The same

evening I took the 7 o'clock train to Yokohama to engage my servant's

services again. On

arriving at his house he evinced little surprise at seeing me a month

earlier than I had told him to expect me, and, on my asking the

explanation, said that he had several times lately been to consult a

uranaisha.

Without telling the uranaisha

where I was, or anything

whatever about me, he simply asked him if he could tell him "where my

master is." On two occasions the seer could tell him no more than that

his master was many thousand ri

away. On the third occasion he had

received the information that his master was on the sea, returning to

Japan. On the fourth occasion—that very evening at half-past five—he

had gone again, and the diviner had told him that I was not ten ri

away, and that he would see me again that night. At the moment he

secured this information I was actually within ten ri, and I called,

as

the diviner said I would. These episodes may be accounted for by

coincidence, of course. I have simply stated the facts and no more.

There are several uranaisha at Inari.

The photograph shows one of them,

in consultation with a woman of the peasant class, selecting his

divining rods preparatory to instructing her in the matter concerning

which she has come specially to Kyoto to see him, whilst her mother and

brother stand by, anxiously awaiting the verdict of the oracle. The

pair of ishi-doro

to which he has fastened his sign-banner are typical

of the severity of the style of the stone lanterns at this temple.

The circuit of Inari's grounds is a good

three miles' walk, and one may

spend hours wandering amongst its many shrines and long avenues of

wooden torii,

which in places are erected so close together as to form one long

continuous

arch—each torii

almost touching its neighbour. There are many thousands

of them in the temple grounds—perhaps tens of thousands, if one

includes the miniatures that are stacked about the principal

shrines—varying in size from six inches in height to fifteen feet. They

are painted vermilion, with black at the base, and form a brilliant

contrast to the deep green of the trees.

The photograph was taken in the tallest of these avenues, and shoves

the old woman with her bird cage and another fortune-teller.

The

torii,

characteristic of every Shinto temple, is not as nationally

distinctive as some protest. Its whole meaning is a matter of

contention. Most authorities claim for it Japanese origin as a perch

for sacred fowls (tori)

which time has modified to a mere "symbolic

ornament." Kipling claims it is Hindu, and at Alwar, in Rajputana,

India, one Hindu temple that I visited has almost its exact

counterpart. The beautiful pai-lo of China is the same idea in a more

embellished form. Be its origin what it may, the torii is a very

striking and effective structure, and its dignified lines are much

beloved by native artists. The numerous torii at Inari are

the gifts of

devotees whose supplications have met with favourable response.

There are a score or more other temples

in Kyoto in which one might

ramble for days and always be discovering some beautiful or curious

feature, hitherto unnoticed. At Kitano Tenjin there are bronze bulls,

which shine with a beautiful patina brought out by centuries of

friction at the hands of those who rub them, as they rub Binzuru's

image at Kiyomizu, to gain relief from their ailments; and there is a

fine old oratory round which to run a hundred laps is a penance that

purifies the heart as effectually as it strengthens the body.

AN AVENUE OF TORII AT INARI

Sometimes a dozen zealots may be seen vying with each other

in the task.

Myoshinji, whose massive buildings lie

deep in groves of magnificent

pine-trees, has many works of art, and a revolving bookcase, to turn

which lays up as great a store of merit as if one read the whole of the

scriptures it contains. Daitokuji boasts of a larger number of valuable

kakemono

than any other temple in Japan, and has an entire set of

sliding doors, dividing room from room, painted by the famous Kano

Ten-yu. Uzamasa is famous for its statuary. Kodaiji was beloved by

Hideyoshi, who used to sit on a certain spot in its galleries and revel

in the beauty of the moon, as he also did at Nishi Hongwanji. Eikwando

is embosomed in glorious groves of maple-trees, and Shimo-Gamo has

groves that are more beautiful and grander still. Here on the 15th May,

at the annual festival, horse-races, in which the priests take part,

are held on the broad reaches of turf among its splendid

cryptomeria-trees; and a grand procession of warriors, with armour and

accoutrements of feudal davs, leaves the Imperial Palace to visit the

old temple, just as it did of old when the Mikado came in person.

So holy is this procession that no one

in the crowd may have his head

above another's; and not all the War Office and other official permits

I possessed could gain for me the privilege of an elevated position to

photograph it. At the very last moment ere the procession arrived I was

unceremoniously ousted from the vantage point I had taken up with the

permission of the police, who, by thus changing their minds when it was

too late for me to prospect for another place, robbed me of a fine

chance to secure an interesting picture.

The stately old buildings of the

Kurodani monastery, whose ponderous keyaki-wood doors

are strapped and bossed with bronze, contain a blaze of golden glory in

embroidered

silken banners, and its state apartments are as rich in art as its

situation is in natural beauty.

At such places as

Kurodani, Chio-in, and Eikwando, one goes not only to see the temples

themselves, but also to feast the senses in the matchless harmony and

grace with which the hand of time has clothed their surroundings. None

but the most artistic people in the world could have designed or

conceived such grand, reposeful settings; and the passing of the

centuries has but added the soft charm that only time can give. There

is an atmosphere of simple dignity about these temples that touches the

very soul. One cannot approach them except with reverence. One cannot

enter them without being purified in mind; for thoughts are elevated

to loftier planes, and no believer in the faith these grand old

structures adorn, nor any other believer either, could ever seek their

precincts without deriving some benefit from the act. All their beauty,

and the careful and imperceptible merging of the art of man with the

handiwork of nature, is planned to calm the spirit and bring rest and

joy to the troubled heart. Anger is dispelled, grief softened, and

anguish tempered to him who roams their lovely grounds with reverent

mind, and a feeling of blessed contentment and rest enters into his

soul.

This is truly the zenith of the art of

raising a sanctuary—to invest it with the atmosphere of peace.

An old gentleman, whom I met at

Kurodani, as much enchanted with this

lovely land as I, said to me: "But you cannot feel such joy as these

beautiful places bring to me, for you are much too young a man. You

have youth and strength, and are busy storing up a fund of memories for

the days when youth is past and strength departed. Not till then will

you really appreciate the full charm of what you are now seeing. I am

old, and the

peace and restfulness of this land is to me but the foreshadowing of

the peace I soon must find for ever. I am glad that I came to this

gentle country, and would ask no better fate than to end my days among

such beautiful surroundings."

1) Rikisha-runner.

2) Murray's Handbook

3) For a most interesting and exhaustive essay on the meaning

and

history of cha no yu

from its earliest days see B. H. Chamberlain's

Things Japanese..

4)

Murray's Handbook.

5) The

mortuary shrines to the Tokugawa Shoguns at Nikko owe their splendour

to Buddhism, though many Shinto features were introduced when the

latter was established as the State religion at the commencement of "the Enlightened Era."

CHAPTER III

THE ARTIST-CRAFTSMEN OF KYOTO

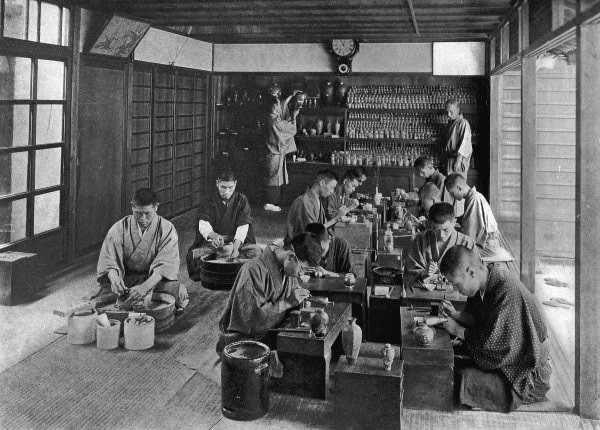

In the old-time houses that line Kyoto's old-time streets

ancient arts

are perpetuated and kept ever young. Arts, too, that are not yet

middle-aged, and others that are as yet but in their cradles, find in

Kyoto the inspiration to give them their fairest and noblest

expression. Bronzes, embroideries, porcelain, damascene,

cloisonné,

iron-wares, silks, and a number of other products for which Japan is

noted, come mainly from Kyoto; and visiting the places where these

are made is as interesting as "doing" the regulation sights.

Nothing short of a book could do justice

to the hours I have spent with

Kyoto artist-craftsmen. About Kurōda alone many pages could be filled,

but here I can only relate some simple incidents and facts.

Kurōda is a bronze-inlayer whose only

compeer is Jōmi. He is a very

tall, stern-looking, clean-shaven man, and speaks English fluently with

a deep rich voice. Few who have not been to Kyoto know anything about

the artistic marvels created under his roof. His masterpieces are never

seen in any shop, for, like a few others of his contemporaries, he

scorns all dealings with the trade. His output is small, but he finds a

market for it all with visiting connoisseurs.

At either

Kurōda's or Jōmi's one may see triumphs of the bronze-worker's art

superior to anything ever produced by Nagatsuné, Jinpo,

Toshiyoshi, or

any of the old-time masters, for though many native crafts are being

degraded

by appealing to the most vulgar of foreign tastes, that of

bronze-working, one of the most beautiful, more than holds its own with

the work of previous centuries.

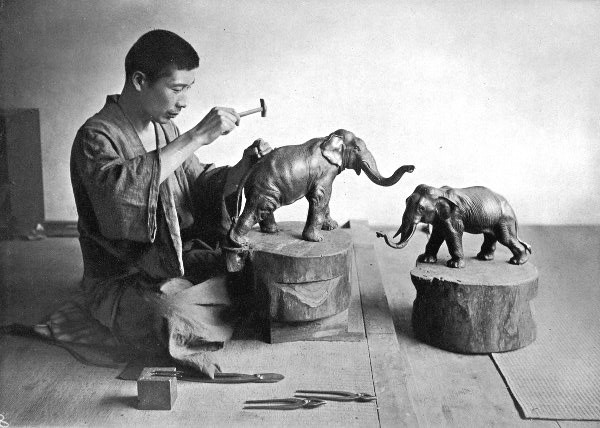

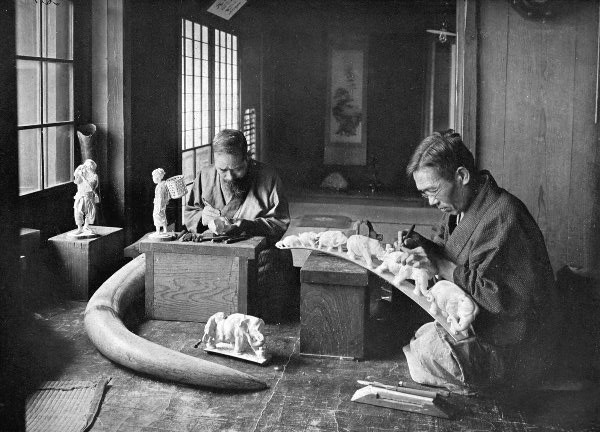

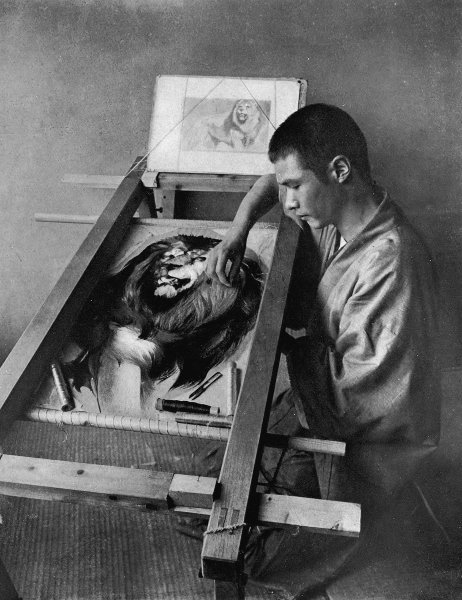

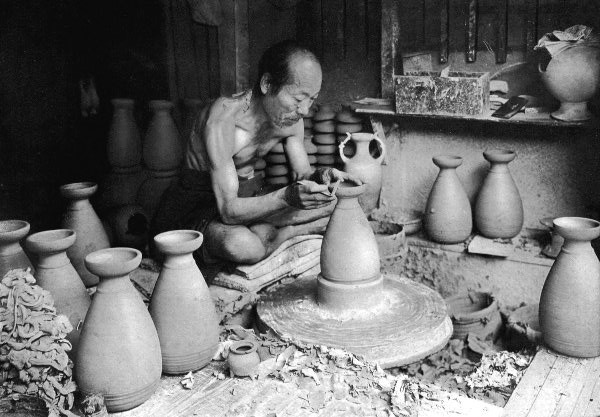

THE BRONZE SCULPTOR

I owe much to Kurōda for

what he taught me. Though I had spent a lot of time in the shops of

other metal-workers, I had been groping in the dark until I met him. On

my third visit to his place he said: "You seem really anxious to

learn about my work, so I am going to teach you. Very few foreigners

understand anything about bronze, though most of them think they do. To

show my finest work to many foreigners is a thankless task, as they

cannot see why one piece should be worth four or five times as much as

another that looks almost exactly like it. Even an educated Japanese

does not know anything about the fine-arts of Japan unless he is a

collector."

With that he went to a near-by shelf,

and,

after much careful deliberation, selected a box from a number of

similar-looking ones of various sizes, and, opening it, produced a bag

of brocaded silk, from which he drew out a bronze plaque.

"Now what do you think of that?" he

asked, handing it to me.

I carefully examined it. The bronze was

of a beautiful rich

golden-brown colour, with an exquisite patina, or polish, and was

inlaid in relief with silver and gold, and with shakudo and other

alloys of bronze.

The design represented the famous Bay

of Enoura, from Shizu-ura by the Izu peninsula. Silver-tipped waves

were lapping the shore, and out on the ocean two golden junks were

running before the wind, with silver sails bellying to the breeze. By

the beach there was a grove of old pines, in various alloys, and in the

distance Fuji-san's snowy crest, of silver, floated in the sky above

clouds of shihutchi (a grey alloy of silver and bronze). The price was

£8.

I had certainly never seen anything more

beautiful, either in design or

workmanship, in any shop I had previously visited, and said so.

"Do you know what I think of it?"

Kurōda replied, and continued

without waiting for an answer: "What you are looking at is nothing

but mere rubbish. No Japanese collector would bestow a second glance on

it. Now I will show you what a Japanese, who knows, would call good

work."

With that he opened another box, and

brought

forth another plaque of like size, about seven inches in diameter, and

handed it to me. The design was the same, yet not the same. The

composition of the picture was different, though the view was still

Enoura Bay, with Fuji and the junks and pine-trees. But it was not the

difference in the composition that struck me so much as the surpassing