CHAPTER XV

MATSUSHIMA AND YEZO

Matsushima ranks in Japanese estimation as one of the three

most

beautiful places in the country; but not every foreigner sees it with

Japanese eyes, and the charm of the famous bay near Sendai is

completely lost on those who go there for an hour or two and rush away.

Matsushima is one of those places which must be studied leisurely and

in detail, and seen in this way it fully deserves its renown.

As the name implies, Matsushima is an

archipelago of pine-clad islands—on the east coast about two hundred miles north of Tokyo. It is said

that there are no less than eight hundred and eight of them, all

composed of soft volcanic tufa which the erosive action of the waves

has worn into most fantastic shapes. Each of the islands is named;

one, for instance, being designated "Buddha's Entry into Nirvana,"

whilst a little bunch of a dozen is called "The Twelve Imperial

Consorts."

I arrived at Matsushima station one

lovely

morning in August, and took a rikisha

for the village, distant about a

couple of miles. As we passed a cutting between two hills my kurumaya

suggested that I should walk to the top of one of them and see the

view. I did so, and am glad that I first saw this beautiful place thus.

First impressions have a lasting effect, and though, in after years, I

saw the island-studded bay under less favourable conditions, Matsushima

always remains in my memory as I saw it on that August day.

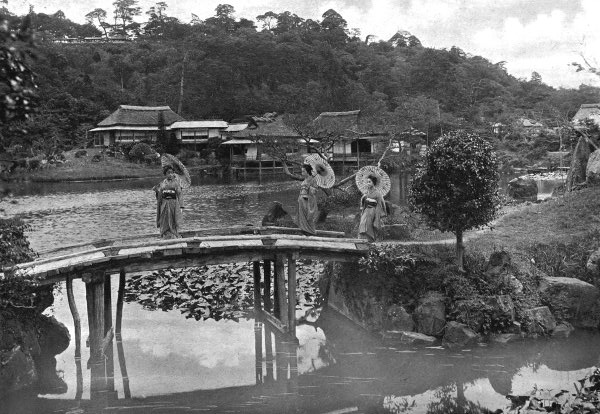

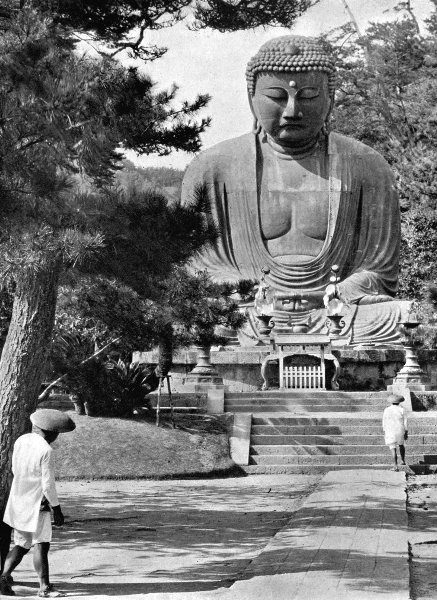

ON MATSUSHIMA BAY

It was only a few minutes' walk

to the top of the eminence, from which

the view is famous as one of the fairest seascapes in Japan. The neat

village lay close below, and a precipitous little island, with sides as

steep as the wall of a house, rose out of the sea not ten yards from

the shore, to which it was connected by a rustic bridge. From among the

pine-trees that covered it a temple peeped, and a line of sampans were

anchored at the quay near by. Scattered about the bay, in every

direction, were other islands, seemingly painted on a mirror, for the

surface of the sea was unruffled by a breath of air. Banks of soft

cumulus clouds filled the skies, and here and there a boat sent long

widening ripples across the water to prove that the scene was real. The

summer chorus of the cicadas about me was a deafening pandemonium.

Wee-wee-wee-wee-wee-wee-wee-weeeeeeeea

screamed a thousand of them in

the pine-trees, till my ear-drums seemed to whistle with the sound. Yet

I love these noisy insects, for their song is always merriest when the

weather is warmest and brightest, and Japan in bright weather is

fairyland itself.

A Japanese dearly likes to see a

foreigner appreciate the beauty of the land. He takes it as a personal

compliment to himself. My kurumaya,

who had come to the hill-top with

me, chuckled with delight at my comments on the scene, and there were

even tears in the old fellow's eyes. I do not know any people so easily

touched by a few appreciative words as the Japanese. When we reached

the road again he had to recite all my remarks to the other man (who

was waiting with the luggage), to the equal pleasure of the latter; and

when we arrived at the inn my appreciation was repeated again by the

two of them to the landlord

(with, doubtless, copious amplifications, judging by the time it took

to tell), and the landlord retailed the facts to the servants in a

longer version still, so that I was persona grata with

the lot of them

just because of my favourable impressions of the place.

I wasted no time in chartering a sampan,

and we were soon under way to see the principal sights. For the whole

of that day and the next we cruised about that "calm and quiet bay on

a level shining sea," visiting island after island, each more grotesque

than the last, and exploring caves and natural arches and every

whimsical freak that the sea could carve in stone. Each island is

crowned with a few pine-trees, even to the very smallest, which is but

a few yards in area. How they grow is a mystery. Many of them appear to

find subsistence in the solid rock, and every crevice is occupied by

one or more. They grow at every angle, as often as not leaning down to

the water, or horizontally over it.

Some of the

islands have tea and summer houses on them; some are carved with

Buddhas; one has long rustic bridges connecting it with the near-by

shore; but the finest sight of all is the view from Tomi-yama. From

this place on a clear day the scene is of simply bewitching beauty. The

sea bristles with islands and promontories, "land and sea being mixed

in inextricable but lovely confusion," *1 and the surface of

the

water is streaked with currents and tide-rips that change in colour

with every hour of the day, whilst every cloud that floats over the bay

changes the composition of the picture. The largest of the islands is

the holy Kinkwa-zan, which has been a Mecca to pious pilgrims for

centuries; but the day I had planned to visit it was wet and stormy,

and, though I waited for two days more, the storm only increased in

violence, and I was reluctantly obliged to give up the idea, as I

intended going still farther northwards to the island of Yezo.

Being volcanic, Japan is therefore beautiful; but this axiom is less

obvious in the most northern of the four great islands of the

archipelago than in other parts of the Empire. Yezo has its charms,

however, and as I crossed the sapphire Tsugaru Strait one hot, sunny

September day, and saw the pretty tiled-roofed, wood-and-paper

houses of Hakodaté nestling at the foot of the great

Gibraltar-like rock known as the Peak, I decided that no other port in

Japan looked fairer or more inviting, not even the far-famed Nagasaki.

The town was clean and neat, and business seemed to be in a thriving

and prosperous condition; coolies were everywhere, bustling about with

bundles of cured fish, bags of rice, bales of dried seaweed, and other

merchandise; and the bay was full of shipping. My entry into the

Katsuta Inn confirmed the good impression already formed. It was

immaculate in its cleanliness. My window looked out on to the harbour,

which is a miniature Hong-Kong of activity; and if anything were

needed to complete the fitness of the simile, the mountain towering

above the town filled the blank, for it is but a small edition of

Victoria Peak, which dominates Britain's South-China colony.

It is well to drink in such beauty as one finds in the situation of

Hakodaté. The farther one penetrates into the island the

more

one becomes impressed with the fact that Yezo is an untidy country—as

inferior to the main island as Hawaii is to Java. Indeed, one is

irresistibly reminded of Hawaii, for the whole mountain region round

Hakodaté bears a striking resemblance to the surroundings of

Honolulu. In their unkempt appearance the fields at once recall those

of the vaunted islands of Mid-Pacific, the beauty of which has been

greatly overrated by writers who have not gone far enough afield to

find the much lovelier isles lying in that usually gentle ocean.

Though the Tsugaru Strait is not more than ten miles wide at the

narrowest part, it is exceedingly deep, and has severed the island of

Yezo from Hondo, the Japanese mainland, for untold ages—if indeed these

lands were ever joined at all. North of the Strait the fauna and flora

are as different from those found south of it as if they belonged to

widely-separated countries. We are told that there are no monkeys in

Yezo, nor any pheasants; and that even the bears are of an entirely

different species from those of the mainland.

The

singing birds are numerous, a most remarkable thing, for the more

temperate islands to the south can boast of none save larks and

nightingales.

My object in coming to this

little-visited part of Japan was to see the Ainu, that strange, hairy

race who were the aborigines of the land before the Japanese arrived

and took it from them. The nearest Ainu settlements, however, are a

hundred miles or so up the east coast, and this necessitated our

embarking again on a small steamer for the port of Muroran—a place of

little interest, which is reached in about nine hours.

Before embarking on this journey I spent a day visiting the lakes

Junsai-numa and 0-numa, and the volcano Koma-ga-dake. This trip is an

interesting and pretty one, and fills a good hard day. Junsai-numa is

very shallow—not more than ten feet deep at any part—and, according

to the guide-book, furnishes fishing "with a worm." Fishing is one

thing, however, and catching fish quite another.

AT MATSUSHIMA

To Junsai it would not be necessary nowadays to take a creel

to hold the

spoils, for the boatmen who rowed me across it vowed that there was not

a solitary fish left in the lake. Ō-numa is much deeper and larger, and

has some pretty islands. Both the lakes lie at the foot of the volcano,

which rises to a height of 3860 feet.

The ascent

of the mountain is quite easy. Starting from the eastern end of Lake

O-numa, I arrived at the crater's lip in an hour and a half; but this

was not to the highest peak, which is said to be inaccessible. The

crater is an immense one, but only a small portion of it is now active,

and the walls are badly broken down.

There are

many places on the east coast near Muroran where colonies of Ainu are

to be found, the largest of these being at Shikyu and Shiraoi. I was

accompanied thither by a Japanese interpreter. On the way we turned

aside for a day or two to visit the great solfataras of Naboribets,

which are among the most interesting natural phenomena of Japan. The

large and comfortable hotel at which we put up was thronged with

Japanese visitors, who come here to enjoy the curative properties of

the mineral hot-springs. The water is piped to a long series of public

baths, ranging in temperature from about 105° F. downwards.

These

baths are very interesting. Here, at one's leisure, one can study

Japanese humanity of both sexes in a state of nature. The baths are the

meeting-place for guests at the hotels, and a convenient rendezvous for

the gossips of the village. All meet on a common footing, man and

woman, youth and maid, young and old, rich and poor—and I was going to

say dirty and clean; but the Japanese are never dirty, unless one

includes the Ainu, who are a distinct race and type.

Comfortably immersed to the neck, the sexes mingle together, and laugh

and talk as freely and unrestrainedly, and with equal courtesy and

etiquette, as in their own or each other's homes.

It is some two miles to the solfataras, which are the crater floors of

an exceedingly old, double-vented volcano, with towering precipitous

walls, whose jagged serrated ridges—burnt brilliant red—frame with

weird grandeur and beauty the awful abomination of desolation of the

sulphur-beds below. In all Japan one cannot find a more interesting

example of a volcano which has destroyed itself than these solfataras

of Naboribets. The vividly-coloured walls are a striking object-lesson

in geology. The lower lava bed is covered with several hundred feet of

black ash and red cinders, which were ejected by the volcano for ages

after the foundation of lava was formed. When later the heavy lava rose

once more into the great cup, and filled it up to the brim, this

unstable pile of loose tufa was broken down, and a terrible cataclysm

must have occurred when the vast rent in the crater's western wall,

over half a mile in length, was made.

This

self-destruction is in the end the destiny of most really old

volcanoes. I use the word "old" in the geological sense. Fuji, for

instance, is but a baby as volcanoes go, and, though called extinct, is

merely dormant, as the steaming fissures on the lip would seem to

testify. Fuji has not yet marred its beauty by bursting its crater's

rim.

On the north, south, and east sides of

the

Naboribets volcano the abrupt, inflamed walls stand in a great

half-circle round the sulphur-mounds and the lakes of

boiling-sulphurous water, which now cover the bed of what was

originally a crater floor. The whole of this huge solfatara is

honeycombed with great yawning cavities, some of which emit fearful

sounds from the seething cauldron below, and belch vast columns of

steam at terrific pressure to the heavens above.

There are pools of soft, sticky, bubbling, sputtering mud, and

cauldrons of boiling water as clear as glass; and there are fountains

of boiling liquid mud, and geysers of boiling water of crystalline

purity, spouting with equal ferocity but a few feet apart. There are

great cavernous apertures, twenty feet or more in diameter, encrusted

with lovely sulphur crystals—fragile as foam—and little holes, not an

inch across, each adding, according to its powers, to the general

pandemonium, and imparting its tribute to the boiling, sulphur-tainted

river which springs from the crater's heart, and flows hissing,

seething, and splashing over the treacherous surface as though the

eternal fires were but a foot or two below.

The

noises of the place are many and varied. Some of the holes emit a

muffled murmur; others almost scream; whilst others again give out

sounds of such fierce boiling as are truly terrible to hear. As we

cautiously wended our way amongst these safety-valves, over hills of

flower-of-sulphur, and pumice, and vermilion ash, carefully poking the

ground with long sticks before venturing each step—for to break through

the crust would have meant a hasty end—we came at length to a great

hole which gave forth a most bloodcurdling sound. As we approached, it

breathed a deep sigh, and then sent out a wailing shriek, as if some

monstrous creature were in agony. For a few moments both I and my

Japanese friend stood rooted to the ground in fear. To run would have

been to court destruction by stepping on some weak spot in the

treacherous crust. We did not know what was coming next. For my part I

expected the ground to open and engulf us, or a boiling geyser of mud

and sulphur to overwhelm us; and not till some minutes after the wail

had died away into a sigh and silence, did we realise that this was

only another of the harmless, intermittent noises of this diabolical

place.

Curiosity would not be satisfied till we

had taken a look into the great hole from which this hideous sound had

come. We went to the edge, and as we stood by the gaping cavity it gave

forth deep and regular sighs as of some cyclopean creature breathing.

Indeed, so real was this resemblance that if we shut our eyes and

listened, it was easy to understand how impossible it would be to

dispel the belief of ignorant savages, such as the Ainu, in the

existence of some great and terrible subterranean monster near at hand.

According to the Ainu creed the world is governed by the Goddess of

Fire; and as they have in their midst such an appalling manifestation

of the pent-up power within the earth as these solfataras, it is easy

to see how such a belief obtains.

We waited near

the spot, and in a little over half an hour the sound came again. More

horrible than ever it was, as we were now on the brink of the hole, but

long before the scream had reached the climax of its power, we had

retreated as fast as the necessity of carefully choosing our footsteps

would permit. We felt that this hole was not to be trusted. Though one

often takes risks from curiosity, one's inquisitiveness is considerably

damped when the prospect confronts one of possibly being overtaken by

such an uncomfortable method of dissolution as would be afforded by

such terrible natural forces.

I have seen many

volcanoes and solfataras in several lands, but never one that emitted

such truly horrible sounds as this. It is certainly not surprising that

an ignorant race of aborigines, living in a land of these natural

wonders, should have had the fear of fire instilled into their hearts,

and have formed the belief that the world is ruled by a deity whose

abode is in such places.

A SEA-WORN ARCH AT MATSUSHIMA

As evening drew nigh, swallows in thousands circled and twittered about

the bastioned, blazing precipices, which glowed with every colour in

the rays of the setting sun, and as we traced our steps homewards the

tumult of the place lingered in our ears for a mile, like the roar of a

rock-bound coast beaten by the angry waves of the sea.

The next morning we left for our objective point, the Ainu settlement,

and the nearer we approached it the more slovenly became the methods of

the farmers and the condition of their millet and other crops-Although

the fields were owned and worked by Japanese, they bore little

semblance to the trim and beautifully-kept farms of the mainland.

We arrived at Shikyu at nine, and put up at the most miserable apology

for an inn that it has ever been my lot to stay at in any part of

Japan. Yet it was the best the place afforded. Our arrival at this inn

was the signal for the greater part of the inhabitants of the village

to come and satisfy their curiosity by staring at us. This stare of the

Yezo Japanese is something which must be experienced to be appreciated.

A man would place his face a couple of feet from mine, and glare into

my features with as much assurance and self-possession as if he were

regarding a poster on a wall. Apparently foreigners were not often met

with in these parts, judging by the intensity of the scrutiny to which

I was subjected. Whilst waiting for the result of my interpreter's

search for a suitable coolie to carry my rather bulky photographic kit,

I entertained myself by returning the native gaze. On one individual

whose eyes were fixed on mine, as if he were under the influence of a

hypnotic spell, I glowered with all the intensity I could. For fully a

minute (it seemed ten to me) I regarded him thus, till, with a start,

the glarer suddenly became conscious of the fact that he was an object

of equal curiosity to me. The instant and complete collapse of his

self-assurance was ludicrous. His eyes dropped to the ground, and he

shuffled to the back of the crowd like a chidden child, whilst several

burly wits made merry at his discomfiture.

It

seemed that much difficulty was likely to be experienced in persuading

the natives of the Ainu settlement, which we were about to visit, to be

photographed. A coolie had been engaged, but it appeared that the man

would not come unless his wife was engaged too. As they knew the Ainu

well we took them both. The man then chivalrously proceeded to load his

wife up with the heaviest packages, whilst he contented himself with a

little case weighing but five pounds. I protested against this division

of labour, but he declared that his wife was much stronger than he,

though she was obviously a fragile little woman and he was as lusty a

fellow as I ever employed.

Then there was a

further hitch, and my interpreter said, indicating the innkeeper: "I

have decided it is necessary to contract with this gentleman also; the

Ainu are so spontaneous and will rebel to submit to the picture. He is

the owner of this house." The last sentence was accompanied with a

dramatic gesture. I cannot say that this commendation carried the

weight with me that it was evidently expected to, and I inwardly

breathed a prayer to the weather-god that he would not entail upon me

the necessity of accepting the gentleman's hospitality longer than was

necessary.

I soon found, however, how

indispensable this man's services really were. I am firmly convinced

that without his help I should have been several days, perhaps, before

securing a single photograph, for the Ainu prejudice against "having

their mere form produced with substance," to use the words of the Rev.

J. Batchelor, is still a deep-rooted one, and cannot be overcome except

by the judicious admixture of gifts and diplomacy—the one as necessary

as the other.

This man proved to be a most

valuable assistant. For two days he was indefatigable in my interests,

and when the time came to pay the reckoning I was quite unable to

persuade him to accept anything for his services. Only with great

difficulty, indeed, could I induce him to receive payment of our hotel

bill. He maintained that it had been an honour to lend his assistance

to any one who came for the purpose of learning about his country. I

have met few like him. Humble as was his abode, and evil-smelling

from the quantities of dried fish stored in it, yet he had a proud and

generous spirit, and I doubt not sprang from stock that had seen more

prosperous days.

We then proceeded to the large

Ainu village at Shiraoi, a few miles distant. My olfactory nerves were

the first to apprise me that our destination was near at hand; the

great distinguishing characteristic of an Ainu settlement is the odour

of dried fish with which everything in it, and about it, is permeated.

Three women were the first of the Ainu to put in an appearance. We met

them just outside the town, carrying large bundles on their backs. They

were young and good-looking, with rosy faces, and hair hanging round

their heads to the shoulders; but their features were badly disfigured

by broad moustaches tattooed on their upper lips—reaching almost to the

ears. This is the prevalent custom amongst almost all Ainu women. The

hair which grows so luxuriously on the face of the Ainu man is lacking

on that of the woman, so to supplement this deficiency the upper lip is

tattooed. Some Ainu women are not content with submitting merely the

lip to this disfiguring treatment, but have thick lines tattooed on

their forehead and arms, and ugly patterns on the backs of their hands.

These marks, however, are considered by the Ainu to enhance their

beauty greatly.

After a consultation with the

chief of the village, a fine-looking old man, whose long beard and

shaggy locks were turning grey, we were conducted to the house of a

prominent member of the community who lay on a bed on the floor, sick

unto death. An old grey-bearded man, whose face was almost hidden with

thick hair, knelt beside him, reciting prayers for his recovery, whilst

many relatives sat round him on the earthen floor of the rude thatched

hut. The dim light was just sufficient to show the sad, anxious

expression on the faces of the silent figures, who indicated so

plainly, by their quiet, gentle manners, the deep concern they felt. It

was a sad initiation into the home life of these poor people, and

respect for their feelings made me take a hasty leave, for I felt that,

under the circumstances, the intrusion of a stranger out of mere

curiosity was quite unwarrantable. The few moments, however, that I

tarried in the hut, and saw this little group of gentle, yet ignorant,

uncivilised figures—gathered together in the sombre interior of a

structure which in some lands would scarcely be thought fit for

cattle—waiting for the approach of the Reaper whose harvest lies in

every land and at every season, left a deep impression in my mind. My

feelings turned from those of disgust at the filthy, animal-like

condition in which these people live, to those of pity, that any human

creatures, dwelling amongst a highly civilised race, should know

nothing better than mere existence in such a state of degradation. Bare

existence and sustenance seem to be the whole ambition of the Ainu, who

are held in utter contempt by the clever, enlightened Japanese, and are

left alone to work out their own salvation.

AINU MAN AND WOMEN AT HOME

The

Japanese name for the Ainu is Aino, the literal meaning of which is

mongrel. This arises from a Japanese tradition that the Ainu are the

descendants of a race of creatures half man, half dog. Little

consideration, therefore, can these humble people expect from their

masterly conquerors.

The huts in which the Ainu live are of

coarse kaia-grass,

thatched with reeds. The roof is made first, then hoisted into place

and tied in position by-creeping vines to the ridge-pole and parallels.

The walls of thatch are then tied in the same manner to poles, driven

into the ground, which support the roof. Each hut has two small

windows, one on the east side, one on the south. The east window is

sacred, and outside it are placed offerings to the gods. At the west

end is the door, and over it a hole in the roof is provided for the

escape of the smoke from the fire, which is made on the ground near the

centre of the hut.

All Ainu dwellings are

constructed in this manner. There are no neat wooden houses, such as

the Japanese live in, for the Ainu wallow in the conservatism of

ignorance, and custom forbids any departure from traditional methods.

Their huts are primitive, uncomfortable, dirty places, reeking with the

odour of dried and rotting fish, which are hung in the roof. Nor are

the people who inhabit them any cleaner, for they have none of that

love of hot water which makes the Japanese, as a nation, the cleanest

people in the world. Personal cleanliness is not the Ainu forte.

Formerly the Ainu dressed in garments of wood-fibre, and many do to the

present day; but Japanese cotton goods are now largely supplanting the

native cloth. Men and women dress much alike, except that the patterns

woven into the fabrics are quite distinctive in character for each sex.

No man would dream of wearing the patterns used by women. When old the

women closely resemble the men in feature, saving for the lack, of

beard. With middle age comes ugliness, but many of the young girls are

very comely. Men and women alike wear their hair about their shoulders

in a thick, bushy, unkempt mass.

The lot of the

Ainu woman is not a happy one. Dirty, slovenly, barefooted, miserably

clad, and disfigured by tattoo-marks, she subsists, a wretched drudge,

to whom life holds out none of the pleasures and diversions known to

the women of other lands. To her, life means naught but work from morn

till night. Not only must she attend to all the household duties, but

she must clean, smoke, and dry the fish; cut and pound out the millet

; cut and carry from the forest the winter's supply of wood; dig up the

fields and sow the crops; and such time as she can find to spare must

be given to helping her lord and master, to whom she is little more

than a slave. There are about her none of the little graces which

distinguish other women of the East. The women of China, of the

Philippines, of Burma, of India, all have some feminine charm; but the

Ainu woman is a poor untutored savage, unlearned even in the

instinctive arts of Eve. One thing she has in common with her sex—the

love of jewellery. Cheapest of metal though they be, she yet loves to

adorn her scanty charms with rings, sometimes on her fingers, sometimes

in her ears. And yet she has one charm that I had almost overlooked;

she is gentle and submissive as a child, and her voice is low and

musical.

The Ainu men are a sturdy, well-built

race, averaging about five feet four inches in height. Their long,

shaggy hair and fine bushy beards give them quite a patriarchal and

even distinguished appearance. The hairiness of the Ainu men is largely

confined to the face. In comparison with the sparingly moustached

Japanese, they are, of course, a hairy race, for their heads and faces

are well covered with a soft, luxuriant growth; but not more so than

the faces of many Europeans. They are grave and taciturn, and laughter

is, it would seem, almost unknown to them; though perhaps this is not

strange, seeing that their mode of life offers little inducement to

merriment.

Drink is the great Ainu vice. Their

appetite for the Japanese rice-distilled beverage saké is

insatiable. "They will not submit to the picture without provision for

the saké

feast. They are so spontaneous," said my interpreter. With the Japanese

fondness for large and ambiguous words, "spontaneous" appeared to be

his adjective for expressing their shy and retiring nature.

I therefore made provision for the

feast, which consisted in purchasing a large tub of saké.

In consideration of this present a selected number of the head-men of

the village were prevailed upon to permit me to photograph them and

their households as I pleased. When this was over the feast began. I

did not wait till the end of the orgie, but I heard that all who

participated in it were intoxicated to a state of absolute helplessness

and insensibility.

Drunkenness being considered among the

greatest of virtues, libations of saké

are accompanied by the observance of much etiquette. The feast was held

in the house of the chief of the colony, and three chiefs from

neighbouring settlements were invited. Each wore a crown of seaweed,

shavings, and flowers. Guests of lesser rank did not wear these, and

women were not invited. As each took his place and squatted on the

matting spread on the floor, he saluted each of the others in turn by

stroking his hair and beard. Host and guests sat in a circle, and it

was a picturesque spectacle, not without a touch of pathos—that group

of heavy-bearded, shaggy-locked figures, squatting in the dim light of

the hut, waving their hands and stroking their hair and beards before

each bowl of saké

was consumed.

The hut speedily became insufferable to me on account of the smoke from

the fire, the stench of the fish in the roof, and the odour of the

number of people partaking in the feast or watching the feasters. Just

over the fireplace—which was simply a bare patch of ground, six feet

long, in the centre of the hut—there hung a wood canopy, the purpose of

which seemed to be to distribute the smoke to all parts of the

structure—which it did most effectively. The combined effect of the

smoke and stench was so sickening that, though my nostrils had become

fairly well accustomed to smells in the East, I was glad enough to

forego the pleasure of witnessing the end of the feast and to regain

the purer air outside.

Hanging from a beam near

the fireplace, so that plenty of warmth might reach it, was a cradle,

and in the cradle was a baby, which steadily screamed throughout the

time we were in the hut. How it managed to scream as it did was a

mystery to me. Any other but an Ainu child would have perished from

suffocation by the smoke. No one soothed it, or paid it any attention

whatever; nor did the guests show that they were conscious of its

screaming. Seemingly it was allowed to cry itself to exhaustion and

silence. This, my Japanese friend told me, is the Ainu custom; to

permit a child to cry itself to sleep is to discipline it, and teach it

the futility of such behaviour.

The interior of

Yezo is largely virgin forest, where few but the Ainu ever penetrate.

These wilds are the haunt of wild bears, though of late years they are

becoming scarce.

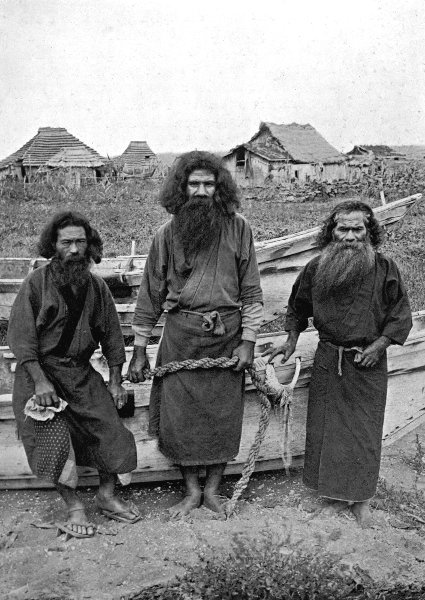

HAPPU KONNO, THE HUNTER (IN CENTRE), AND TWO AINU FISHERMEN

There

is no meat the Ainu prize more than bear flesh. Among the feasters was

a man named Happu Konno, one of the most famous bear-hunters in Yezo.

So striking in appearance was this man—so long, and thick, and shaggy

his hair and beard—that I prevailed upon him to strip, that I might

secure a photograph of him. His body showed no superfluity of hair

beyond that on many Europeans; nor was he of the muscular development

of the Japanese; but he was firmly built and athletic, as he needs

must be to pursue his perilous calling. Whatever may be the

shortcomings of the Ainu, lack of courage in a bear hunt is not one of

them. I heard from this man's own lips, through two interpreters, his

method of attack, which coincided exactly with the accounts of

travellers that I have read.

The killing of a

bear is looked upon by the Ainu as the greatest of all possible feats.

Happu Konno's only weapons are a knife, and a bow with poisoned arrows.

With these he is prepared, if necessary, to beard the bear

single-handed in its lair. If he fails to induce it to come out by his

cries, so that he may shoot it with an arrow, he clothes his body with

a skin and creeps into the bear's retreat, armed with his knife. With

this he rushes upon the brute, and as it rises to embrace him, he

grapples with it and stabs it to the heart. This, however, is an

exceedingly dangerous proceeding; so, if he sees an opportunity, as the

bear rises to fight he dodges under its forepaws and attacks it from

the rear. This manoeuvre has the effect of inducing the bear to seek

safety in flight, and as it emerges from the den, an assistant hunter

discharges an arrow or two into its body. It is only a question of a

few minutes till the poison does its work and bruin is dead. The flesh

round the arrows is then immediately cut out; the poison does not

affect the rest of the meat. There are many hunters in Yezo who do not

hesitate to attack a bear in this manner, but such men are justly

renowned for their courage and skill. The use of poisoned arrows is now

illegal, but nevertheless they are still used surreptitiously.

When not engaged in hunting Happu Konno is a fisherman, equally expert

on the sea or at spearing salmon in the rivers. He is the central

figure in the group standing by the boat. The rivers of Yezo abound in

fine salmon, especially in the season when they seek the fresh water to

spawn. The Ainu catch them both by means of hand-nets and by spearing.

A dug-out canoe is used for spearing. One man stands in the rear to

propel it, whilst another stands at the bow, harpoon in hand. The canoe

is paddled down stream or kept stationary, and as a salmon approaches,

the harpoon is let go, usually with unerring aim, and the fish is

impaled. Harpoon fishing is also carried on at night. A large torch is

used to attract the fish, and as they come to ascertain the cause of

the unaccustomed glare, they fall easy victims to the spear.

Although the Ainu have neither priests nor temples, yet, so says the

Rev. John Batchelor, who has probably spent more time among them than

any other foreigner, "they are an exceedingly religious race. They see

the hand of God in everything. Their great religious exercises take

place on the occasion of a bear feast, removing into a new house, and a

death and burial."

Their religious ideas are not

patent to any casual visitor, but it needs little observation to reveal

the deep superstition which governs all their actions. Their gods, of

whom there are many, must be propitiated by offerings; these are to

be seen everywhere, and consist of willow sticks, with the bark

whittled into shavings, which hang in clusters. A number of these are

placed outside the east end of each hut, and prayers are made to them

each day. They are called inao,

and may be seen by the seashore, or on the banks of rivers, and in

other localities to which it is desirable that the deities who govern

such places should be prevailed upon to bestow special attention. The inao

ensures this. Offerings of deer and bear skulls, placed on sticks, are

also looked upon with much favour by the gods. Hence those who have

been fortunate in the chase make such an altar, and place it at the

east end of the house. The willow wands may also be seen inside the

house; and in case of sickness—if they are newly made, and stuck in

the floor near the fireplace—they will ensure all possible aid from the

Fire Goddess. This is about the extent of the assistance that the

sufferer receives—the offering of inao

and the chanting of prayers.

The Ainu have no arts or crafts, literature or ambition, and appear to

have fewer claims to anything more than animal instinct than any other

race in the East. Their numbers, it is said, are becoming less each

year, and it is estimated that there are now not 15,000 of them

remaining. If they should in course of time become extinct, their place

will be taken by a race to whom humanity in general owes a greater debt.

CHAPTER XVI

THE BAY OF ENOURA

There is a village on the shores of the bay of Enoura—which

lies

between the Izu peninsula and the town of Numazu—that is very little

known to foreigners, except a few enterprising spirits of an inquiring

turn of mind in Yokohama, who tear themselves away each week-end from

their occidental surroundings and sally out to explore the lovely land

to which a kindly fate has led them to earn their daily bread.

I do not believe a tourist was ever

known to turn aside to visit this

place, which is less than an hour's journey by rikisha from the

main

line of the Tōkaido. Certainly no tourist accompanied by a guide ever

went there. No Japanese cicerone would ever do anything so foolish as

to pilot his charges to such a place, for there are no curio-shops.

Indeed, there are no shops of any kind at all; and how dull would the

evening hours be to Guide San if he missed that feeling of prosperous

independence—such an incentive to repose—which comes of mentally

gloating over the sum-aggregate of large commissions earned from the

merchants and curio-dealers whose establishments he has visited with

his Danna San during the day?

No, the tourist will

never hear of Shizu-ura, and Guide San will never turn a hair between

Kodzu and Shizuoka to show that there is anything of interest on the

sea side of the train.

MOONLIGHT AT SHIZU-URA

He will tell all sorts of things about Fuji on the right—and

of praise he could not say too much—but he

will not mention Shizu-ura, or Ushibusé, or Mito, not

because he does

not know about these places, but because he considers it better his

master should not know, lest he might want to go there.

It is even well to read what you desire

to know about Fuji from your

unerring "Murray," as the train, for an hour or more, makes a wide

semicircle round the matchless beauty's base, and not heed overmuch the

gratuitous information which patriotic natives, swelling with pride on

seeing your admiration of the mountain, and anxious to practise

English, may desire to thrust upon you. I once heard a Japanese

proclaim to a car full of American "school-marms"—Manila bound, who

were training it from Yokohama to rejoin their steamer at Kobe—the

following facts (?) in staccato accents:

"Fuji—is—the—highest—mountain—in—the—world. It—is—eighteen—thousand—

nine—hundred—and—seventy—two—feet—high.

It—is—always—covered—with—undissolving—snow."

I gasped at

the fellow's ignorance of the loveliest feature of his own land. Each

of these statements was incorrect, but in getting the wrong altitude

down to two feet he seemed to me to show decided ingenuity. Evidently

here was a man who did not stick at trifles. He would not let lack of

knowledge stand in his way when he saw a chance of making an

impression. He was a Japanese, and must therefore know. So when one of

the "school-marms" appealed to him, he seized the opportunity to show

his intimate knowledge of his country, and scattered mis-information

like chaff before the wind.

The air of patronage and

smug complacency with which he then surveyed his fellow-passengers

through his spectacles was altogether so delightful that I could not

resist the temptation to "take him down." I challenged all three

of his statements, and corrected them, producing my "Murray" in proof.

He was quite crestfallen at this exposure of his ignorance, but stuck

to his guns and maintained that the guide-book was wrong. He then

retired behind his paper, and, at the next station, took the

opportunity to leave the car for another, without the customary parting

bow, doubtless anathematising me in his mind for an ill-mannered,

interfering churl.

As I have already said,

Ushibusé can

be reached in less than an hour from the Tōkaido railway—from Numazu

station, to be exact—but a far more interesting way is to go there, as

I once did in February 1905, by a detour into the Izu peninsula. A

branch line runs from Mishima junction, on the Tōkaido, to Ohito. There

were train-loads of soldiers everywhere that day. At Mishima they

passed us bound for Hiroshima, en route for the Front, making the

station ring with their songs in their joy at going to the war. And on

the way to Ohito we passed two hospital-trains, filled with

convalescents going to recruit at the hot-spring resort, Shuzenji.

These were men who had been to the Front, and knew to their cost what

battles meant.

At Ohito we took a basha for Shuzenji,

for which place we also were bound. A basha is a kind of

small

one-horse omnibus, and this particular one was the cheapest method of

travel I have ever found in Japan or elsewhere. It was a forty-minutes'

drive, yet I engaged the whole vehicle for 45 sen (about

tenpence).

This was the regular tariff, and is a good instance of how prices

shrink as soon as one gets off the tourist track. Near Fuji at least

treble this price would have been demanded. We had just come from the

east side of Fuji, where Yamanaka plain was two feet deep with snow;

yet here—but thirty miles away as the crow flies—the weather was so

warm that the convalescent soldiers, who

filled every hotel and private house, were basking in the sunshine in

their ordinary linen hospital dress.

The Izu peninsula

is the Riviera of Japan, and Shuzenji is its most sheltered and popular

winter resort. I put up at a delightful native inn, the Araiya, where

everything was in Japanese style. My room, which overlooked the

Katsura-gawa, which flows through the town, was of the most immaculate

cleanliness. Its sliding doors were beautifully painted with a pair of

flying peacocks, and the ornament in the place of honour was a piece of

fossil wood resembling the mountains the old Chinese artists painted.

It was curiously carved to represent a band of samurai attacking a

fierce dragon which was issuing from a cavern near the top.

From my windows a scene of constant

interest could be observed in the

river below—from early morn till midnight. A fine hot-spring rises in a

rocky basin in the centre of the torrent, and an open bath-house is

built around it—connected with the banks by narrow bridges. In this

spring men and women bathe promiscuously; and costumes of even the

simplest kind are not considered de

rigueur at all.

As I

was having my lunch, shortly after arrival, two neat little women

stepped from the spring, where they had been bathing in the company of

several of the sterner sex. They walked out on to the bridge, with

their beauty innocent of any concealment, dried themselves in the

sunshine, and then donned their clothes before the eyes of all the

town—only no eyes in the town but mine were looking; for in Japan "the

nude is seen, but never noticed," as Professor Chamberlain puts it.

Such experiences give much insight into the simplicity of the people.

What custom sanctions the conventions

approve, and honi soit

qui mal y pense. In Japan cleanliness is a

higher virtue than godliness, and any exposure of the person, necessary

for this purpose, is both pertinent and proper. Indeed, a few days

before, at Kamiidé, I saw a young man and a young woman,

strangers to

each other, and both guests of the same hotel at which I was staying,

bathing together in a tub which was not more than two feet square and a

yard high, and into which, after the man had entered first, it was

barely possible for the girl to squeeze. The weather was so severe that

any water splashed over on to the stone floor froze instantly; but

they parboiled themselves and chatted and joked with each other for

twenty minutes or more, whilst I was having a lonely bath at the other

side of the room immersed to the chin in a two-foot tub of my own. When

the lady had finished her ablutions she graciously bowed to what she

could see of me above water and then returned to her apartment, clad in

nothing but her chastity—a somewhat scanty garment for so cold a day.

There is nothing of any particular

interest at Shuzenji except the

hot-springs, so next day I started out for Mito in a basha. The

distance is about five miles, and the scenery is worthy of no

particular comment until the end of the journey is reached. Indeed, the

most interesting object on this journey was the basha-driver

himself.

He was a regular character—just as much of a character as are some

London 'bus-drivers. His questions, and comments, and sallies of wit

never ceased until the journey's end, except for the moments when he

drew a few whiffs from his pipe, which he did frequently. Each time he

refilled it he knocked the hard fire-ball of ash, which remains in the

pipe when Japanese tobacco is smoked, into the hollow of his palm, lit

the fresh fill from that, smoked it out in three or four puffs, and

then repeated the process.

A FISHERMAN'S CHILDREN

How he could

hold a ball of glowing fire in his hand puzzled me. I tried it myself,

but had to drop it in a twinkling, much to his delight, and he rolled

about on the box so much with laughter that he nearly tumbled off, and

the horse, taking fright, bolted down a hill and landed us all in a

ditch. But there was no harm done, fortunately, and we soon had the

light vehicle out again, and in due course arrived at Mito, where I

paid him off. I was sorry to see the last of him, and wish I could have

kept him longer; but at Mito we had to take to the sea.

Mito is a fishing village on the shore

of a little sheltered bay, with

rugged precipitous cliffs almost surrounding it. A wonderful island

stands like a guardian sentinel at the mouth of the bay, as pine-clad

as the isles of Matsushima; and white-winged sampans sail on

either

side of it, whilst many others lie alongside the stone jetty, or are

beached on the sandy shore. I thought I had never beheld a prettier

place than Mito when I first saw it, but one always thinks that at

every fresh beauty-spot one visits in Japan. Mito Bay is an arm of

Enoura Bay, which in turn is part of Suruga Bay—the eastern part, lying

between the Izu peninsula and the mouth of the Kano-gawa, a river which

runs into the sea just beyond Ushibusé. The whole of this

coast-line is

strangely beautiful, and its charms have been perpetuated in every form

of art.

We engaged a sampan to take us

round to

Shizu-ura. It was a stout, seaworthy craft, made out of natural

finished wood, in which not a single nail was used—the planks being

fastened together with wooden pins—yet the sendo assured us

that it

would weather the roughest storms the wind could blow. The crew

consisted of an old man and his son, splendid specimens of hardy

humanity both, and typical members of the class from which the

Japanese tars are recruited. They were gentle and kindly of manner and

courteous of speech, as becomes men who might well be the reverse,

seeing that their life is a constant battle with the elements. Danger

is but too often the portion of the fishermen on these seas, where a

cloud, no bigger than a man's hand, may be but the precursor of a

typhoon, which, long before their craft can make land, breaks and

scatters death and destruction in its wake. Often have I read in the

papers in Japan, after a sudden storm, that an entire fleet of

fishing-craft had been lost, and their crews drowned to a man.

There is no more interesting class in

Japan than the fisher-folk. Their

customs and methods differ from place to place round the coasts as

widely as though they belonged to different countries. They are the

first Japanese one sees on visiting the land, and the last on leaving

it; and, if the coast-line be followed much, they are continually in

evidence during one's stay. Like most seafaring people, the world over,

they are superstitious to a degree, and unending is the volume of

legend connected with their craft.

Offerings of old

parts of vessels are freely made by them to the sea-gods, as such

things are very propitiatory, and in return the gods send fine weather

and direct the fish into their nets. Fishermen, who have had the

misfortune to be wrecked, hang tablets in the temples, and offer the

gods such relics of the ships as have escaped destruction.

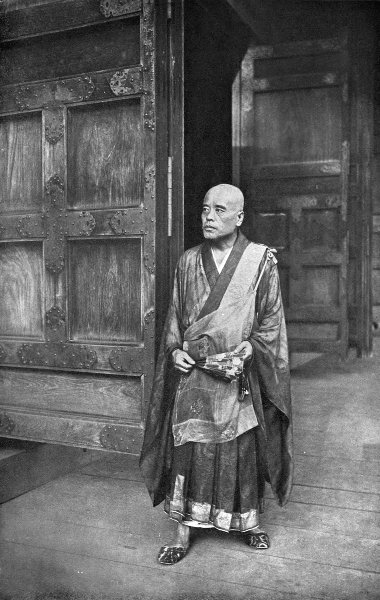

Worship at a Shinto temple before

setting out is very advisable, and

aids in securing a good catch; but should a Buddhist priest be met

with on the way, bad luck is a certainty, as the bonzes do not eat

fish. At least they are not supposed to, but they do.

No worse-omened incident can befall a fishing-craft than that a bucket

should fall from it into the sea and sink,

for, sooner or later, the evil spirits inhabiting the waters will use

the bucket to pour water into the vessel and founder it. A cat must

invariably be carried on a deep-sea fishing junk, as cats have the

power to repel the ghosts that frequent the ocean depths. Should the

cat be spotted or piebald, the greater is its power. The more colours

there are in the cat's coat, and the wider the contrast in these

colours, the higher is its value as a mascot.

I have

spent many an interesting day among the fisher-folk, studying them and

their curious methods. On one occasion, attracted by a group on the

shore, I found that two fine large tubs of whitebait had just been

brought in from a junk. The fish were very small and uniform in size,

being little over an inch in length. The master of the junk stood by,

his hands drawn up into the capacious sleeves of his kimono. Beside him

were four or five excited men who plunged their arms deep into the tubs

and then stood for a moment or two with brows knitted in thought. Each,

in turn, then put his two hands up the junk-owner's sleeves; but the

face of the latter was blank, and gave no indication of the meaning of

this pantomime. No words were spoken, but the meaning of the affair I

quickly guessed. Each of the men was making a bid for the fish, of a

sum unknown to his competitors, by placing in the owner's hands as many

fingers as he was willing to pay yen

for the lot. When all the bids

were in, the highest offer was accepted, and the tubfuls changed hands

for the sum of eight yen

(sixteen shillings).

Our old

boatman's grand-daughter—a little brown-eyed lass of nine—came down to

see us off, with her baby brother on her back. They were the children

of the younger man, and father and son alike were delighted when I made

a hasty photograph of the little maid and told them I would show the

picture to some of my small friends in England.

As we sailed out of the harbour I

noticed that the principal eminences

of the cliffs had bamboo platforms built in the highest branches of the

trees. These are called uomi,

or fish outlooks. When a school of

magaro, or

bonito, enters the bay, a man takes up his position in each

of these. From this vantage-point he can see a long way off, and also

down into the clear water, and observe the movements of the fish. At a

distance the location of the fish is known by the colour of the water;

they come in such great numbers as to make dark patches in the sea. By

a system of signs the look-out men then direct the movements of the

fishermen, who have proceeded out into the bay to surround the shoal

with nets. The nets for this work are of immense length and made of

rope, for the magaro

sometimes runs to several hundred pounds in

weight, and would easily tear its way through anything lighter.

Directed by the look-out men, the fishermen then draw the nets

gradually closer to the shoal until the fish are driven into the

narrowest portion of the bay, across the entrance of which the nets are

fixed, and the quarry imprisoned. They are then caught, and shipped to

Tokyo and other cities as the market demands.

The magaro

is immensely esteemed by the Japanese. It is a kind of tunny-fish, not

unlike a monster mackerel, and is cut in the thinnest of slices and

eaten raw. The fish is the prey of small worms which are frequently to

be found in its coarse red flesh, but this appears to be no objection

to the native palate. I have never been able to face this dish myself,

nor have I ever met any foreigner who could; but some of the daintier

fish that are served raw in Japan are really very nice. The magaro

season is from March to August, and during these months the Enoura

fisher-folk subsist entirely by this traffic.

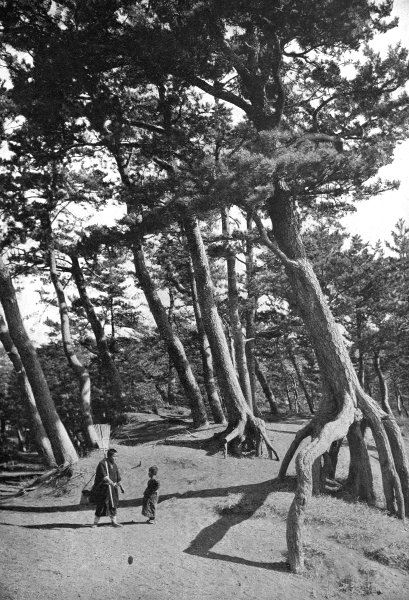

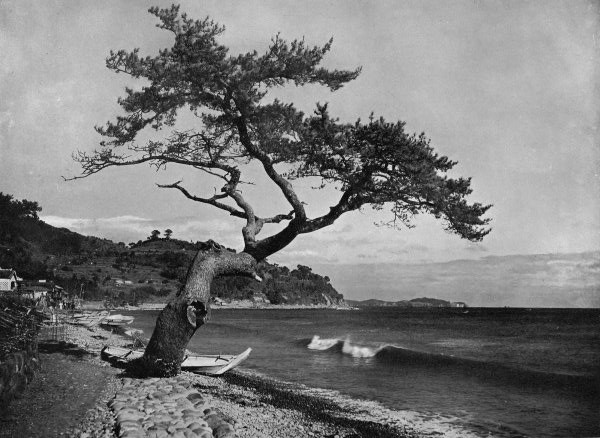

THE PINES OF SHIZU-URA

We sailed slowly along over the

waters of the bay, as the wind was very

light, and it finally dropped altogether as we drew near Shizu-ura.

Then the boatmen took to the yulos

and swung us along at a splendid

pace. The speed that can be got out of this method of propelling a boat

is truly wonderful. The craft was large enough to hold twenty people

quite easily, yet two men sped it onwards at a good four miles an hour

or more. As they yuloed

they kept up a kind of chanty. These Japanese

chanties are seldom as pretty as those of European sailors; but,

though very simple, they are seemingly very eflfective, for the men are

never able to put any real "back" into the work without this

assistance. It is much easier to work hard to some kind of rhythm than

without it.

When the wind dropped the water became

perfectly calm, and so clear that we could see objects on the bottom,

ten or fifteen feet below us, without being conscious of any water

intervening at all.

Huge shell-fish called awabi are

found in the bay. They are easily discovered in water thirty or forty

feet deep by means of glass-bottomed tubs, through which the sea-bed

can be closely scrutinised. When an awabi is located,

it is dislodged

by means of a long bamboo with an iron hook at the end. As this mollusc

has immense muscular power it is by no means a simple matter to capture

it, even when found; it is a univalve, and clings with extraordinary

tenacity to the rock.

Shizu-ura is the name of the long

stretch of sandy beach which bends like a bow from a promontory on

Enoura Bay round to the village of Ushibusé. A forest of

weather-beaten

pines straggles almost to the water's edge, their tortured trunks

clutching the ground like great claws, as they lean shorewards,

strained to

impossible angles by the prevailing gales which blow the sand from

their roots.

As our boat was beached, stern first, on

this lovely strand, there were reasons enough apparent all round us why

its enchantment should have been sung by every Japanese poet. The very

tiniest of wavelets lapped the silver sands, and in the gentle sunshine

each crystal ripple, as it broke, became a row of rainbow opals. Little

children in gay kimonos—the

children of the rich—were playing at the

water's edge, and in the distance the virgin crest of Fuji hung from

the blue sky over the deeper blue of the ocean.

Cheery

little maids came running down the beach to greet us, and carried my

packages up to the hotel embosomed in the pine-trees—the Hoyo-kwan, one

of the finest and best-appointed native houses I ever stayed at in

Japan. As soon as I was settled in my room the host and hostess came to

pay their respects. As they entered, they bowed their heads with much

ceremony to the mats, for the most scrupulous etiquette is observed in

this favourite resort of the aristocracy of Tokyo. There was none of

that free-and-easy manner which characterises one's reception at

Japanese hotels in "foreign style." They sat respectfully by whilst I

sipped a cup of yellow tea, and nibbled at the cakes which are always

brought immediately to the room as soon as a guest arrives. When I told

them that my mission was to take pictures of the country, they evinced

the greatest pleasure and interest, and begged leave to bring and

present to me some of the other guests who were staying there. This

they did that evening, and I entertained them with showing them

photographs I had made of various countries of the world. None,

however, interested them so much as a number of pictures of Japan.

Nothing pleases a Japanese more than to find that a foreigner can

appreciate and love this beautiful land as much as he does himself.

Near the hotel the Crown Prince has a

palatial residence, with spacious

walled-in grounds deep in the heart of the pine woods, to which he

retires each summer from the heat and cares of state of the capital. It

would be difficult indeed to find a more secluded, restful spot, or one

more replete with natural beauty.

This pine grove is far

finer than the famous Mio-no-matsu-bara, twenty miles across the bay,

where the legend of the fisherman and the feather coat, mentioned on

page 380, is founded. Among the weather-beaten old trees—all bent and

twisted by the winds that blow—the peasants, with bamboo rakes, scour

the ground for the needles which are always dropping from the branches,

and which they take home to use as fuel to start their charcoal fires.

The sun by day, and the moon by night, play ever-changing pranks of

light amidst the tortured trunks, and the breezes murmur softly in the

branches to the accompaniment of the waves beating on the shore close

by.

Shizu-ura's beauty is mutable as the

weather's

moods, and one day—when I was out in a boat, peering down into the

depths trying to catch awabi—I

found that the sea was all alive with

pretty nymphs. The sunlight, glinting through each surface ripple, was

decomposed as by a prism, and as the rays pierced downward through the

crystal water they turned the ocean bed into some beauteous palace of

Nereus, in which the rainbow colours, all dancing about its rocky halls

and terraces, were the Nereides, the Sea King's daughters.

My old sendo

was as delighted as I with the sight, for my pleasure

warmed anew his interest in a spectacle with which long familiarity had

bred unconcern. He searched out beautiful and still more beautiful

spots, till he came to a rugged little island. Here he bid me step

ashore, and, beckoning me to a corner in the rocks, said, "Honourably

glancing deign, sir master."

I followed, and found a little

peep-hole, worn by the erosion of the

waves. Through it there was an exquisite vista of Fuji and the

pine-clad strand, framed roughly by the rock—a view made classic by

Hiroshige half a century ago.

"It is the Shizu-ura

Fuji, sir master," said the old man, and the pride glowing in his face

told me that in native estimation this was the climax of Enoura's

wonders.

REFLECTIONS

CHAPTER XVII

HIKONÉ AND ITS CASTLE

The province of Ōmi, one of the most celebrated in Japan, is

equally

renowned for the beauty of its scenery and for the web of historical

memories and legend with which it is interwoven from end to end.

Biwa-Ko, the largest of Japanese lakes, lies in its heart, filling

about one-fifth of the whole province with its waters. Its length is

thirty-six miles, thrice its greatest width, and the depth in places is

said to be about fifty fathoms.

This is the lake which,

according to tradition, fills the great depression that appeared in the

earth during a violent seismic disturbance one night in the year 286

B.C., when Fuji-san burst upwards from the plains of Suruga. Tradition

or fact, such an event in this volcanic-studded land, where the thin

crust covering the eternal fires is always trembling, is likely enough

; and it is only to be expected that a sheet of water which claims its

origin in such an occurrence should have lived up to the remarkable

circumstances of its birth by enshrining itself in beauty and legend.

Some of these legends are to be found in most books on Japan, but about

one of the most charming of Biwa's beauty spots I have never found more

than a few lines in any book at all. Hikoné is its name—a

little town

standing on the east of Biwa's shores, a place about which my memory

lingers fondly.

One early summer's day as I was whirled

up to the porch of the Ha-kei-tei Hotel in a rikisha

I was

greeted by the

assembled female staff with the customary chorus of welcome, only here

the welcome was more than usually warm and hearty. As we entered the

hotel grounds I could hear the shrill voice of the head

maid-servant—who, as at most Japanese hotels, was more remarkable for

her virtues

and length of service than her good looks—calling to the younger girls,

as she detected the sound of rikisha

wheels on the gravel. "O Kyaku

San! O Kyaku San!" ("An honourable guest! ") she cried, and as my

kurumaya

dropped the shafts at the great wide doorstep, the little

neisans

came running from every direction, with many bows, to take my

luggage.

When I had removed my boots—for one

never, of

course, thinks of entering a Japanese hotel with boots on—one of the

neisans led

me to my room. As we passed along a dark corridor I had the

misfortune to bump my head against a beam in its low ceiling. This

mishap proved altogether too much for the composure of the little maid.

She leaned against the wall, laughing till the tears filled her eyes,

and the whole establishment, coming to see what was the matter, and

finding me ruefully rubbing my pate, laughed as well. The little

incident put us all on good terms at once, for, seeing that I could

stand a joke against myself, every member of the domestic staff was

soon my friend; and when one makes friends with the staff at a

Japanese inn, they in turn do everything to make one's stay as pleasant

as possible.

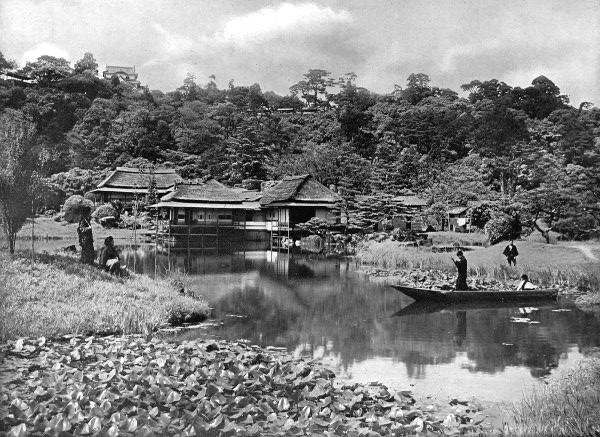

The hotel is charmingly situated by a

lake

in one of the most famous gardens in Japan; and the room to which I

was shown was built out entirely over the water with a verandah on

three sides of it. This ornamental sheet of water is a facsimile of

Lake Biwa, all the famous sights of which are duplicated in the

miniature.

THE HA-KEI-TEI INN AND GARDEN AT HIKONÉ

There is a long rustic bridge representing "The Long Bridge

of Seta"; a maple-clad hill stands for the mountain Ishiyama, and

another one is Hirayama—the "evening snow" on the original of which

is the second of the "Eight Sights of Omi" in native estimation. There

is even a curiously-trained pine-tree as proxy for the veteran of

Karasaki—the arboreal giant of Japan, and one of the most curious trees

in the world. The "Karasaki-no-matsu," on the opposite shore of Lake

Biwa, is not only the greatest pine-tree in Japan, but also the most

sacred. This patriarch, though now not more than forty feet high, has

branches which stretch their crooked length well over a hundred feet

from the old trunk. They are supported on a small forest of props, and

are so low that one has to duck one's head to pass under them. All

holes in the trunk are made water-tight with plaster, and a roof over

the broken top keeps the rain from entering and hastening decay.

The pine in the Ha-kei-tei garden is not

of any great age—a mere

century or two—nor is it large, but it is very picturesque. During my

stay two gardeners spent the greater part of three days going over all

its branches and carefully plucking out about three-fourths of its

needles. This was done for a double object; to give it that spiky

appearance so greatly admired by the Japanese, and also to stunt its

growth. Such trees are subjected to this treatment every two months,

and to root-pruning once a year.

The Ha-kei-tei garden

was a never-ending source of delight to me. I was alway finding some

fresh beautiful peep through its maple-trees, or among its islands and

the bays and gulfs and outlets of its lake. Every evening the carp

nibbled noisily at the lily leaves, and swallows fluttered over the

surface of the lake. The swallows nested under the eaves of the hotel

and even inside its porches. This is considered a lucky omen. No

Japanese would think of disturbing a swallow which took up its abode in

his house.

Another and larger hotel—the

Raku-raku-tei—has a garden adjoining, but although it also has a

"lake," no fish nibble at the lily leaves, for the lake is only an

imaginary one, and has no water in it. This garden is in the severest

cha-no-yu

style, and the lake is simply a bed of pebbles, with islands,

bridges, overhanging pines, stepping-stones, and all—everything save

water, which the imagination of this highly idealistic people easily

supplies.

These gardens were formerly the

pleasure-grounds of one of the most powerful feudal families, whose

fine old castle stands on a hill overlooking them. The last feudal

Lord, or Daimyo, of the Hikoné clan was Ii-Kamon-no-Kami,

the sage and

diplomatic noble who acted as Regent for the young Shogun

Iémochi in

the troublous times preceding the Reformation. For leaving this lovely

country-seat and mixing himself up in politics he paid penalty with his

life; he was assassinated in front of the General Staff Office in

Tokyo on the 24th March 1860. His castle (O-shiro) is one of

the very

few of such edifices now remaining in Japan. Shortly after the period

of Meiji was inaugurated the Japanese, disgusted with everything of

their own creation, were seized with a mania for razing all such

structures to the ground. The destruction of Hikoné castle

had already

commenced, when it so happened that the present Emperor, being at that

time on a journey to Kyoto, passed this way, and seeing what the local

officials had begun to do commanded them to desist at once. Thus the

old castle was rescued from the fate which threatened it, and it stands

to-day one of the finest and most picturesque features of feudal Japan.

It was the custom in the old days for a

Daimyo, when he found his bones

ripening with years, to abdicate in favour of his son. When such an

event happened at Hikoné the ex-Lord retired to one ot the

residences,

now turned into hotels, in the castle grounds. It was in one of these

charming houses that I now found myself, and as I stood by the shoji of

my room on the evening of my arrival I thought that no other place in

the world could be more beautiful or restful. I stepped out on to the

verandah, and immediately great carp, which had been loafing on the

muddy bottom of the lake, glided up to the surface, just below me,

sticking their heads almost out of the water in the expectation of

being fed.

I wandered out into the garden among the

maples and stone-lanterns, and found an almost hidden path, walled in

on either side with blocks of rough-quarried stone. This led to a

stairway in the outer wall of the castle, the steps of which ended in

Biwa Lake. It was one of the most beautiful and romantic spots I have

ever seen. The reeds growing far out into the shallow water were full

of frogs, and the very air was ringing with their croaking. Every now

and then some solitary crow, flapping his way lazily overhead, would

augment this evening chorus with a few hoarse caws; and the crickets,

which were just tuning up for the night, added a shrill soprano

accompaniment.

Rugged, purple mountains were reflected

in the golden lake, whose surface was broken only by the ever-widening

ripples in the wake of a boat which was approaching, whilst the sendo

sang a song as he slowly yuloed

it. The boat came across the foreground

of the picture, and pulled up at the mossy stairway where I stood.

Imagination was beginning to conjure up all sorts of possibilities

about it, and the tubs with which it was laden, when a coolie came down

the stairway

bearing two other similar tubs on a yoke across his shoulders. Alas!

my dream was over, for the aroma which insulted the air told that his

burden, and the cargo of the singing boatman's craft, was manure for

the rice-crops. Such is Japan! Whilst there is "so much that appeals

to the eye, there is also not a little that appeals to the nose," as

Professor Chamberlain archly remarks; and these rude shocks to the

senses are but too common.

I turned away and wandered

over towards the hill on which the castle stands. Its slopes are

thickly covered with pine and maple-woods, where the hawks breed

unmolested and are always soaring in the skies. At the bottom of the

hill there is a broad moat banked high with sloping walls of stone. The

water is much overgrown with aquatic plants, and there are many curious

bamboo fish-traps in it. As I stood beside the quaint old bridge—which

stretches over the moat in a single span supported by many

props—watching the afterglow playing pretty tricks of colour in the

water,

the daylight waned away, and I heard the tramp of men-at-arms and the

sound of many hoofs coming down the roadway from the castle. First,

through the gateway and across the bridge came swift outrunners to

clear the way; then at the head of the band appeared mounted knights,

clad cap-à-pie in lacquered armour—cuirass, morion, tasses,

and all—and

with swords stuck in their girdles and gleaming spears butted in their

stirrups. Behind them marched the foot-soldiers, clad in armour too,

with bows and arrows across their shoulders and a pair of swords in

every belt. On they came, making the old wooden bridge shake and echo

with their tramping, and swung along the road with swaggering air and

short quick steps towards the town.

AN OLD FEUDAL CASTLE FROM THE MOAT

In the middle of the train was a

mettlesome cob, ridden by a noble figure of a

warrior in vermilion lacquer and mail, with enormous wings spreading

from his helmet and white plumes dancing between them. I knew him for

the Daimyo at a glance. It was the feudal Lord of Hikoné,

going off,

perchance, to make a raid upon the Daimyo of some neighbouring

province. I watched them pass along the road and disappear into the

twilight, among the leaning pine-trees and the cloud of dust raised by

their feet. When the tramping died away in the distance I turned

hotel-wards along the back of the beautiful old moat, and into the dust

which still hung in the air; only it was not dust at all but a film of

night-mist rising from the water, and the Daimyo and his samurai were

but a vision, born of the reverie into which I had fallen. A few days

before I had seen, in Kyoto, a pageant of an old-time feudal procession

which once every year leaves the Imperial Palace and proceeds to the

ancient Shinto temple of Shimo Gamo. Each participant was clad in

armour to represent a samurai

or his feudal chief; and as I stood in

the twilight on this romantic spot, imagination, responding to the

surroundings, had seized the chance to make them the setting for a

vision of the spectacle I had lately seen.

All night

long, as I lay in a comfortable bed on the floor of the old Daimyo

house, I had a vague consciousness of samurai clattering

down the hill,

and carp leaping in the moat. There was nothing unreal about the

sounds, however, for whenever I woke up, as I did several times, I

heard the carp splashing in the water, and the rats were making a

terrible noise as they raced over the thin, resounding boards overhead.

The next morning I went up to the castle, and apropos of this visit I

find these lines in my notebook, inscribed on the spot:—

Hikoné,

May 1903.—If I only make one visit to this castle it will

always remain in my mind in connection with a crowd of hundreds of

school-children who have come to picnic for the day in the castle

grounds. They are in charge of their teachers, and are running all over

the old courtyard and woods, shouting with delight.

The

natives have girded their loins to do justice to the occasion, and

justice is undoubtedly being done. The cake-man, the fruit-man, the

iced-drinks-man, the air-balloon-man, the ice-cream-man and the

toy-woman—all are here. There is also a man who has a number of small

tubs of different coloured sweetstuffs, and when young Japan presents

his farthing, he gets a cockleshell heaped up with the sweetmeat in

layers of blue, red, green, yellow, and white. There is another man,

old as old can be, with face as wrinkled as the rind of a musk-melon,

whose trade it is to dip from a bowl of batter a small portion, and

spread it on the face of a sheet of bronze laid over the glowing embers

of a htbachi. He flattens the sputtering mess out with a stick, until

it is as thin as a wafer, and in an instant it is cooked. Then he takes

in his hand a lump of sticky sugar and ground rice and rolls it out

between his palms till it is four inches long; this he lays on the

cookie and rolls all up together. About these stalls children of

assorted ages, from six to sixteen, flock like moths around a candle,

and the small coin of the realm is quickly finding its way out of the

purses in the children's girdles to the pile of copper before each

vendor.

During this and later years, however, I

made

more than one visit to the castle, when it was quite deserted, and

explored every nook and corner of its halls and garrets. In one of the

rooms of the keep a fine display of old armour is preserved. Several

suits that belonged to the Daimyo

are magnificent examples of the Japanese armourers' art. They are made

of many small strips of iron, coated with vermilion lacquer and

fastened together with leather thongs and silken cords. His helmets,

kabuto,

have immense horns or wings—like those on the winged cap of

Mercury, only much larger—and between them hangs an enormous white

plume, which, when in use, must have fallen well below his eyes. There

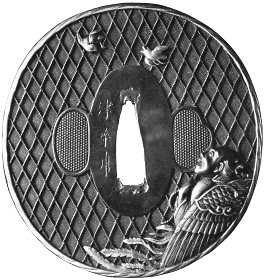

are swords and spears of such workmanship and mounting as to

delight the soul of any one who loves such things, and many other