CHAPTER XX

THE INLAND SEA AND MIYAJIMA

Miyajima! Even the very name is soft and pleasant to the ear, as is

befitting for a queen's; and Miyajima is easily queen of all the

lovely isles which grace that fairest stretch of water in the world—the

Inland Sea.

It was from the prettily-situated

port of Kobe—which lies at the foot of the Settsu mountains, by the

waters of Izumi Bay—that I embarked on a small Japanese steamer for a

visit to the far-famed island.

At ten o'clock one

summer night in 1904, we weighed anchor, and soon entered the Akashi

Strait, which forms the principal eastern entrance to the famous

landlocked waters. The moon, which was at the full, shed soft radiance

over the motionless sea, and the little vessel's bow cut the glassy

mirror like a knife, causing tiny jets of spray to fly upwards and fall

back with a hiss on either side. As we glided along past the island of

Awaji—which was the very beginning of Japan, the home of the Creator

Izanagi and the Creatress Izanami, where they settled and gave birth to

all the other islands of the Japanese archipelago—we found ourselves in

the midst of a fleet of junks, busily engaged in fishing by the light

of the moon.

Like phantom ships upon a phantom

ocean, they lay with idle sails which tried in vain to catch a breath

of wind, and reminded me vividly of that memorable hour when first I

saw Japan.

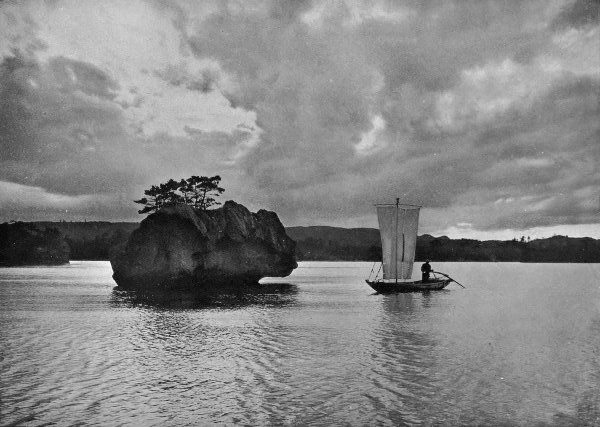

All next day we were passing through

narrow channels, where the tide ran swift and strong, or over vast

sheets of open water which seemed like inland lakes. Junks and fishing

boats were sailing everywhere, and the scenery was weirdly beautiful.

Grotesque islands of every conceivable size and curious shape—all

carved and crannied and pock-marked by the erosion of the swift

currents, and studded with fantastic pine-trees leaning over the water,

as often as not at angles far below the horizontal—were bestrewn all

over the surface of the sea; and our course was altered almost every

minute to navigate the tortuous winding channels.

The engine-room telegraph was constantly ringing. One moment the helm

board was "hard-a'port," the next it was "hard-a'starboard," as the

fitful currents came swirling round the rocks, and the steamer heeled

from side to side as the rushing waters caught us on either bow. Now

and again it seemed almost impossible that we could stem the flood. At

one place the little vessel rushed headlong to destruction as she

steered for the cliffs hemming us in on every side. But at the moment

when her doom seemed sealed, the precipice parted asunder and an

opening appeared. Quickly, and timed to the second, went the word of

command. Hard over went the helm, and the staunch, obedient little

craft, heeling over and nearly standing on her beam ends, strained

every bolt and plate as she turned her head to answer, and then swept

with a rush through a narrow channel, where the tide was racing like a

mill-stream.

We made brief stoppages at many

small towns and villages, but the most picturesque of all was Onomichi

—a pretty little port with plenty of bustling activity about its

streets and quays. There is a large island called Mukojima in front of

it, from which it is separated by a long and narrow strait. This

channel is always

haunted by a fleet of old-time junks; but the ancient native rig is

now rapidly disappearing from Japanese waters in favour of brigs and

schooners, which can sail a good deal closer to the wind.

At high-tide the activity of Onomichi's water-front is strenuous; and

when the tide is low, long stretches of sand lay bare, and hundreds of

women and children dig for shell-fish. Near the town large areas of

land are used for growing reeds for making matting, and salt marshes

line the shore for miles. The system of extracting the salt is very

simple. The water which percolates through the sand is collected and

evaporated in the sun until it becomes concentrated brine; this is

then evaporated again, by boiling, till only the salt, encrusted on the

pans, remains.

A fine old bell at Senkoji monastery,

high up in the hills above the town, sent deep sweet notes trembling to

the breezes; and out in the strait the white-winged junks skimmed

continually over its shallow emerald waters. Fishermen sailed away to

the west as the sun went down, to return with their spoils at break of

day; the laughter of rollicking children mingled with the murmur of

the rippling waves that lapped the shore; and everything on land and

sea seemed to breathe of a world at peace.

Yet how

deceitful were appearances! Japan was not at peace, but engaged in

bitter, deadly strife for very existence. There was, however, no shadow

of the struggle at Onomichi, where we stayed for the night.

The next day, on another steamer, we had further tussles with the tide

and currents, and though she fought them bravely she was baffled more

than once. At one place a great swirling whirlpool yawned before

us—fully ten feet or more in depth—seeming like the gaping mouth of

some

great sea-monster seeking whom it might devour. But our little vessel

only laughed at it, and swept

across its vortex, dispersing it for a moment as she passed.

Then she throbbed easily along until she came to the Ondo channel. But

here her strength failed her. Though she put all her power into the

task she could not breast the flood which boiled through the narrow

passage. Thrice she tried it, but in vain. She could not keep her head

to the current; and the moment she wavered it caught her side and swept

her reeling back into the open reach again. It was quite an exciting

struggle, and though the captain kept her stubbornly to the task, he

had to abandon it at last and wait for slacker water. In half an hour,

when the tide was running slower, he tried again, and the little vessel

fought her way foot by foot up the channel, past a great stone lantern

standing on a rock in its middle. There were villages within

biscuit-throw of us on either side—so near that we could look into the

windows of the houses, whose inhabitants scarcely turned from their

occupation to watch the struggling steamer, so accustomed were they to

such sights. On another occasion, when I passed through this channel,

the tide was running just as strongly in the contrary direction, and a

similar conflict had again to be waged against the current.

Then we turned and twisted about for hours through landlocked channels

and lakes, amidst seascapes of bewitching beauty. Island after island

bobbed up out of the sea—some no larger than the steamer, mere

pinnacles of granite, but seldom without a few whimsical pines sticking

to some crevice into which they had found a chance of forcing their

starving roots. Others were lovely symphonies of colour—great pyramids

of green, rising a thousand feet or more above the villages on their

shores—and terraced like a stair-way

with rice and barley patches to their very summits.

EVENING ON THE INLAND SEA

Not an inch of

earth was wasted. Every tiny village and hamlet had its temple,

sometimes by the shore, sometimes perched upon a knoll; but more often

than not it peeped from some clump of pines, far up the mountain-side,

where the patron deity might feast his eyes for ever on some glorious

view.

As we sped along through all this wonderland, the

scenes in the depths below were beautiful as the views above. The

sunlight pierced far down into the clear water, and by leaning over the

bow, where the surface was undisturbed by the vessel's progress, I

could see lovely gardens on the bed of the sea.

We were

floating over the silent realm of the Nereides, and could see the

beauties of their home as a soaring bird looks down upon the earth.

Sometimes there was nothing but the blue of infinite depth below us;

then some submarine peak would stretch upwards, almost to the surface,

with great forests of sea-plants on its top, which waved their foliage

to us as we passed.

When Aphrodite herself was born and

sprang like a lily from a bubble on the sea, that lily could not have

floated upwards from a fairer spot than this; and as I gazed into the

depths, with the spell of their magic upon me, I half expected to see

some lovely sea nymph beckon me with her hand; but instead the sea

trees only waved their branches. There were shoals of fish among the

greenery, and in one of the open reaches we ran into a school of

dolphins. Scores of the playful cetaceans were just below us, easily

keeping pace with the steamer with scarcely any perceptible movement of

their bodies. They seemed to take keen delight in swimming an inch or

two ahead of us, and in leaping out of the water as near as they could

to the vessel's prow.

Then the sea began to swarm with jelly-fish. We found them massed

together in such prodigious numbers as actually to impede our speed.

There must have been countless billions of them for a mile or more, for

scarcely any water could be seen for the multitude of the creatures. We

seemed indeed to be steaming through a monster jelly. The Japanese call

them kurage, which means "Sea Moon." This name is most appropriate,

for a single kurage in the deep blue water resembles very closely the

full moon in the sky.

Then we came to Kure, the greatest

of all the naval harbours—the Portsmouth of Japan. It is said that the

hills hereabouts are lined with impregnable forts, but though I have

passed them many times, and scrutinised their sides closely with my

glass, I have never, except at Shimonoseki, seen a sign of a

fortification on the Inland Sea. They undoubtedly exist, however, and I

can only conclude that they are so well and skilfully masked as to be

invisible from the water.

In the harbour, which on my

visit here a year earlier was filled with battleships, cruisers, and

torpedo craft, a solitary gun-boat represented the naval might of the

nation. The deserted aspect of the place was ominous. It spoke plainly

of the Titanic struggle in which the other ships were participating,

for Port Arthur had not yet fallen, and the entire battleship fleet of

Japan was keeping a ceaseless vigil in the Yellow Sea.

At Ujina fourteen transports lay at anchor, and the whole place was

seething with animation. Japan at that time was like a boiler under a

high pressure of steam, and Ujina was its safety-valve. Into this place

thousands of troops were being poured weekly, and as rapidly being

poured out again in the troopships which

left daily for Manchuria. The Aki-maru, at that time the largest vessel

ever built in Japan, was taking on board three thousand soldiers, and

five thousand other troops were leaving the same day on several of the

smaller troopships.

The hospital ship Kosai-maru had

arrived in the morning from Manchuria, filled with wounded soldiers

from the Front. As she lay at anchor in the sunshine, her dazzling

white hull relieved by a single red line from stem to stern, she looked

more like the plaything of a millionaire, a thing of peace, than the

hideous spectre of war and grim shadow of suflfering and death which

the great red crosses on her funnels revealed her to be. As we glided

past her, lines of stretchers, on each of which lay a shattered hero,

were being carried down her gangways to the waiting sampans, A constant

stream of these craft plied between the vessel and the shore, and

another stream of them was bearing outward-bound soldiers to the

waiting troopships.

After an hour's stay we left Ujina,

with its feverish activity and reflections of the war, and, turning a

rocky promontory, beheld Miyajima in all its loveliness ahead. It was

now evening, and a faint mist rising from the sea was gradually

enveloping the sacred island with a veil, as though its guardian

deities—the Sea King's daughters—were jealous of their trust, and

sought to hide its beauty with a garment. It was a thin, diaphanous

robe, however, and served merely to add the witchery of enchantment to

the charms it could only half conceal.

Now if Miyajima

had been in the Aegean Sea the Greeks of old would have called it

Delos, and they would have invested it with legend. They would have

said that poor Latona, condemned by the jealous hatred of Juno to

banishment from Mount Olympus, and to everlasting roving o'er the earth, arrived at length on the

seashore, and there entreated Neptune to pity her distress. And Neptune

would have heard her prayer, and sent a dolphin to bear her to a

wondrous floating island which he had raised especially for her from

the loveliest depths of his domain. Then when the isle had floated to a

certain spot—where the waters were crystal clear, the breezes soft and

balmy, and the air all sweet and scented—he would have anchored it

fast; and there Latona would have lived happily for ever with Jupiter,

her lover.

All this and more the Greeks did say about

their legendary isle; but even Delos could not have been more

beautiful than Miyajima.

As we approached, that summer

evening, it seemed indeed too lovely to be real. It was like a dream—a

vision of some spectral isle which, even as we watched, was slowly

melting away into the vapours of the shadowy seas of fable.

But the queenly island had only thought to tantalise by shrinking thus

from view, for as we drew nearer to its shores a sudden change of whim

caused it to abandon provocation, and to cast off all conceits and

modesty and show its beauty—naked. We glided out of the filmy

enshrouding mists which lay about the surface of the sea, and fair

Delos of tradition became fairer Miyajima of fact.

Its

forest-clad peaks and spires were outlined high against the twilight

sky, and the sweet scent of its pine-trees was heavy on the air. We

steamed along, close under the precipices which overhung the water,

and, as the whistle blew to signal our arrival, the blast smote the

rocks like a blow, and then went leaping from ledge to ledge up the

mountain-side, setting all the forest ringing, and awaking a thousand

echoes in its trail.

MIYAJIMA

Then

many lights came into view, and we drew alongside a little stone pier;

but by the time I had engaged a coolie, and had my luggage loaded on a

barrow, half an hour had gone, and we started off through the village

to the Haku-un-dō Hotel in the dark. I could see but dimly, therefore,

all the beauty we were passing, for the moon had not yet risen above

the island's crest. But I knew that old temple buildings loomed up out

of the shadows, and that the beach was all dancing with ghostly fire as

the ripples broke into attenuated gleams of phosphorescence on the

strand. And there were long rows of ishi-doro silhouetted against the

water; and by the light of the coolie's lantern I could see deer,

frightened by its glare, skip nimbly out of our way. Then there were

fragrant pine-groves, with turf as soft as velvet; and at last a light

appeared in the heart of the pines, and then a house, and as we drew up

to it there was a chorus of "Irasshai, Irasshai'' ("Welcome,

Welcome"), from the host and little neisans, who had gathered round the

door as soon as they heard the coolie's shout.

Greetings

over, I was immediately taken in charge by one of the little maids,

who, by the light of a paper lantern, led me over the springy turf, and

under the pine-trees, and across a rustic bridge spanning a murmuring

stream, till we arrived at a neat little wood-and-paper summer-house of

two rooms—all by itself This, she intimated, was to be my domicile;

and then, after lighting a lamp for me, she pattered off to bring some

tea and cakes. After I had sipped a cup or two of tea she led me to the

bath, and when I emerged therefrom, half an hour later, she was waiting

to conduct me back to my doll's-house once again. Then she pattered off

to bring my dinner—which was, of course, served on the floor—and

she knelt opposite to me and chatted and joked with me whilst I was

having it, asking me many questions about where I had been and what I

had seen.

After dinner she slid open the end of the wall and brought out

bedding—futons, and even sheets, a rarity in Japanese inns—and made my

bed up on the floor. Then she dived into the wall again and unearthed a

huge green mosquito-net, which she hoisted by means of rings at each

corner of the room, completely filling it. After that she lit an andon

(night-lamp) for me, and, kneeling on the floor, and bowing her glossy

head to the mat, sweetly wished me "O yasumi nasai" ("Honourably

deign to sleep "), and then ran oflf to do a lot more work before

having her own bath and going to bed herself. It was nearly midnight

before I knew, by the shouts of laughter coming from the direction of

the bathroom, that she and the rest of the hotel staflF were having

their evening tub before retiring to their futons.

I slept that night to the murmur ot running water and the chirping of a

million crickets in the surrounding woods.

The next morning I was up betimes, before fair Miyajima had shaken oflf

her night kimono of mist. Long shafts of golden sunlight were

struggling with the haze amidst the scented pines, and deer were

browsing on the sweet velvety turf in front of the hotel. The sea was

burnished gold, and junks were lazily drifting homewards like

snow-white swans across its surface. The night-song of the crickets had

given way to the droning of cicadas; and already, although it was but

shortly after sunrise, the woods were ringing with their drowsy hum.

The prospect was a dream of peaceful beauty.

I went down

to the water for a swim, and found the rocks all alive with

sea-cockroaches. Every island in the Inland Sea swarms with these

curious creatures.

They scuttle out of the way, with much ado, as soon as any one

approaches, and then peep furtively from the crevices in the rocks, and

watch you with great eyes until you go away, when they scamper out

again immediately. I swam about for an hour in the tepid sea, which was

so perfectly clear that, on the bottom, over twenty feet below, I found

I could see and pick up pebbles with perfect ease. The water is always

clear here, even in rough weather, for the sand is all coarse

decomposed granite; consequently there is no matter to become

suspended in the water and discolour it.

For ages

Miyajima had been accounted by native connoisseurs one of the three

most beautiful places in Japan. The other two of the San-Kei, or "Three Principal Sights," are Matsushima in the north, and

Ama-no-Hashidaté on the west coast. Miyajima, however, easily

outranks the

other two. It is one of the holiest of many holy islands in the

Japanese Archipelago, being dedicated to three Shinto goddesses—the

daughters of Susa-no-o, the Sea King—after the eldest of whom it

receives its alternative name—Itsukushima.

Human beings

may neither be born nor die within its sacred precincts. Should,

however, a birth unexpectedly occur, the mother would be sent to the

mainland for purification for thirty days; and in case of a sudden

death the corpse must at once be removed to the opposite shore. Dogs

are not permitted on the island.

Apart from the great

beauty of the scenery, Miyajima's chief attraction is its temple, which

is unique, and has furnished many motives to native artists. The best

known of these motives is its torii—a colossal one, made of camphor

wood—which forms one of the chief features in every view of the sacred

island. This

toriihzs been immortalised in every form of Japanese art. From whatever

point one looks at it, it is a thing of beauty. At low water it stands

on the sand; but as the tide rises the sea comes rippling all around

it, until it seems to sail away far out on the bay, and the water is

more than a fathom deep below it.

On the "17th day of

the 6th moon" great crowds flock to Miyajima, for this is the date of

its annual festival. Instead, however, of coming on foot and in

rikishas, as they do to other religious edifices, the people come in

boats, and sail in long procession to the temple, through the great torii which is its main gateway. Even the temple itself seems afloat,

for it is built on piles, sunk deep into the sand, and the rising tide

creeps under and all about its galleries and colonnades, setting them

all waist-deep in water.

A branch of the temple stands

on the hill above. It is an enormous building, called Sen-jō-jiki, or

the "Hall of a Thousand Mats.'' A mat being six feet long by three

feet broad, the area of this hall is therefore eighteen thousand square

feet. Its interior is completely covered—walls, pillars, doors, and

all—with wooden rice-ladles. This queer custom was started as recently

as 1894, when troops were quartered here preparatory to leaving for the

war with China. One of the soldiers one day hung up a rice-ladle in the

temple "for luck." Others followed suit, and every one who has since

visited the temple has donated a wooden spoon, inscribed with his name,

until every available inch of the interior is now covered with this

curious decoration.

Behind the temple and the town,

which is full of shops for the sale of pretty boxes and wood carvings,

the mountain isle is covered with a thick forest of pine and maple

trees to the very utmost of its numerous peaks.

THE OLD TORII AT MIYAJIMA

On the top of the

highest of these, eighteen hundred

feet from the level of the sea, there is a temple where Kōbō Daishi

lighted a sacred flame over a thousand years ago, and this, like the

Vestal fire of ancient Rome, is never suffered to go out. During the

eleven centuries that have passed since the day when the famous saint

kindled it, it is said that the holy flame has been carefully watched

by day and night, and has never been extinguished.

Miyajima's forests are broken by gorges and ravines, where limpid

streams leap down the rocks in dancing cascades on every side, mingling

their laughter with the chorus of the myriad cicadas in the trees. In

summer-time the whole island is all trembling and murmuring with these

sweet voices and with the musical sounds of nature in the fairest and

most winning of her moods. Deer roam down from the hills to haunt the

avenues of mossy granite lanterns by the shore, and to lick the tasty

salt from the rocks, or nibble at the biscuits which every visitor

gives them. As one passes the temple, tame pigeons fly from its roofs

and settle on one's hand and shoulders, begging to be fed; and there is

an enclosure where great cranes, as high as a man, lean over the bamboo

fence and hungrily gobble up the live fish which an old woman sells for

three sen a glass.

Although I was furnished with a

signed and sealed document from the War Department granting me

permission to photograph, yet, during the entire time I was on the

sacred island, on this my first visit, I was under the supervision of

the police. An officer accompanied me everywhere, and when I set up my

camera he insisted on carefully scrutinising the view on the focussing

screen before permitting me to make a picture. This precaution, I

presume, was in order to satisfy himself that the forts—several miles

behind me, on the other side of the island, with mountains nearly two

thousand feet high between—had not, in some miraculous manner,

become included in the view. That was the only obstacle to the complete

enjoyment of my first visit; but on a subsequent occasion this

vigilance was relaxed.

The night I left Miyajima was

lovely as a dream. The tide was high, and a sampan came to the beach to

take me over the Strait. Fiery ripples were breaking everywhere along

the shore, and, as we pushed off, phosphorescent flames burst in the

water at every stroke of the boatman's yulo. As he stood in the stern,

swaying backwards and forwards, with the ghostly wake of the boat

burning in the water behind him, his silhouette seemed like some

uncanny apparition.

I thought of Charon plying his

worm-eaten craft, filled with departed souls, across the river Acheron

to Pluto's realm; and I half wished that I had not been able to pay

the ferryman's fare, for then perhaps this Japanese sendo would have

declined to take me away from beauteous Miyajima—even as Charon made

every soul wait one hundred years who could not produce the obolus he

demanded as his fare.

As I wrote the notes from which

this chapter springs I had the beauties of charming Miyajima all around

me; and now, as I prepare these final lines for the press, memories of

the many happy days I have spent in that exquisite Japanese Arcadia

surge vividly to mind, and a great yearning comes over me to be back

there once again.

I long to wander once more along by

its mossy old stone lanterns; to lie in the shade of its scented pines

and watch the passing junks; to hear the croaking of the hoarse old

crows and see the lazily-soaring hawks; to roam among its maple woods

and listen to the murmur of its hundred waterfalls; to glide at night

over the moonlit sea and hear the songs of the boatmen, and

to drink to the full of each and every other pleasure that fair

Miyajima has to give. But most of all I long to see once more the

changing colours of sunset framed in the beautiful simple lines of the

old sea-beaten torii.

THE END