CHAPTER XII

CONCERNING JAPANESE WOMEN

One of the most charming features about travel in Japan is

that one

cannot pass a day without being more or less under the gentle influence

of the women.

In China or India one may travel for

months and never have occasion to address a woman, for there every

servant is a man, and the women do not enter into the foreigner's life

at all. But in Japan it is different: and how much pleasanter! For

woman is a great power in Japan, and her sphere is a large one. The

home is woman's province: so is the inn. Little soft-voiced women fill

your every wish and, quite unintentionally, make you feel how

indispensable they are to very existence from the time you enter a

hostel in Japan to the time you leave it. Life at a Japanese inn has a

charm that at first you cannot define. Perhaps you do not try to. You

only know that you find it fascinating, but you do not ask yourself

why. Certainly it is not the degree of comfort that pleases you so

much, nor is the food particularly to your taste. Yet you find you

prefer to live at native inns instead of "foreign-style" hotels. Why

? If you ask yourself the question, the answer is easy. It is because

you feel the sweet authority of woman the moment you enter a Japanese

house. That is the charm. With all its beauty Japan would not be the

fascinating holiday-land it is were it not for the gentle, happy little

women who minister to your comfort and every need; whose faces are

wreathed in

perpetual smiles, and who cheerfully fly to do your bidding at any hour

of the day or night, no matter how unreasonable your foreign wants may

be.

Whatever woman's position may have been

in the past,

and whatever it may even be to-day, outside the inn—I cannot say home,

because I have had no experience of Japanese home-life, though I

suspect it does not differ very much in this respect from life at an

inn—there can be no two opinions about the part woman plays inside the

household. She is an autocrat, and a clever one, for she rules even

where she does not really pretend to rule; but she does it so

tactfully that, whilst the husband holds the reins, he does not see—or

at least he does not show that he sees—that his little wife has got

the bit firmly between her teeth, and he is simply following wherever

she chooses to lead.

But woman is not only pre-eminent

in the house, she is fast becoming a very important factor in the whole

social and industrial system of the country, and whatever may have been

the relative status of man and woman in Japan in days gone by, there is

little doubt that another generation or two will see the sexes as much

on an equal footing as they are in almost any other country, for women

are proving themselves fully as competent as men in many occupations.

One now sees female assistants in all the large Tokyo shops; female

clerks in post-offices; female operators at telephone exchanges; and

female ticket-sellers at the railway stations.

The

Japanese girl is no longer content to remain a pretty chattel of the

home. Her emancipation is progressing by leaps and bounds, and she now

expects, and is allowed, such freedom as must rudely shock her

grandmother when the old lady thinks of the days when she was in her

teens. Healthy athletic exercises, every day at

school, are fast changing the entire physique of the modern Japanese

girl, and she is already larger, and heavier, and longer-limbed than

her mother. She demands fresh air and country walks, and the habit of

going unattended to school has bred in her an independence that enables

her to walk the streets unnoticed, and without fear of molestation.

From the standpoint of the older people

this change is not altogether

for the good, for she is losing some of that feminine charm which

caused Lafcadio Hearn to describe her as "the sweetest type of woman

the world has ever known." The submissiveness, which was one of the

Japanese girl's principal attractions, is less noticeable in the

present generation than the last—so I am told by Japanese friends, who

look upon American notions of school training with pious horror. Modern

progressive ideas, and the higher education, are encroaching more and

more into the family circle, and undermining the Confucian foundations

on which it has rested for so many centuries. The Japanese girl of

to-morrow will perhaps consider herself as good as her brother, and may

even not hesitate to match her opinions against his. The time is far

distant, however, when Japanese women will clamour for votes; though

it has come, and passed by, when they were able to demonstrate to all

the world that their services were almost as vital to the country in

time of war as those of the men.

Even though the

Japanese girl grow less passive under the modern system of education,

she is never likely to lose her place among the daintiest and most

winsome of her sex, as the refining processes that have gained it for

her are never likely to be omitted from her training, no matter what

new features are introduced.

The position which the Japanese wife

occupies in the respect and

affections of her husband even to-day is but little understood, for so

much misinformation has been disseminated about her that a wholly wrong

impression is generally held of one who is the most amiable of man's

helpmates in the world. The Japanese home is perhaps the most difficult

of any to gain intimate access to, yet almost every globetrotter who

dashes through Japan is a self-constituted authority on the gracious

matron who presides over that home, and many make the unpardonable and

fatal mistake of classing the modest, retiring lady of the land, whom

probably he never sees, with the popular favourites of the capital and

the treaty-ports.

Even the humbler members of the

Japanese feminine world—such as waitresses and hotel servants—have

been cruelly maligned, and represented to be what they never at any

time were, as their pretty, fascinating ways are often misunderstood by

those who come from lands where customs are so different, and who

cannot speak the language. "Too many foreigners, we fear," says

Professor Chamberlain, "give not only trouble and offence, but just

cause for indignation by their disrespect of propriety, especially in

their behaviour towards Japanese women, whose engaging manners and

naive ways they misinterpret. . . . The waitresses at any respectable

Japanese inn deserve the same respectful treatment as is accorded to

girls in a similar position at home."

No class of

Japanese womanhood is more misunderstood by foreigners than the geisha.

The geisha

has no prototype in Europe: she is unique—a purely Japanese

creation. To mention the name geisha

amongst English people

unversed in matters Japanese is to cause uneasy looks and suggestive

smiles. Why the geisha should be so misapprehended is difficult to

tell.

GEISHA

I

have often wondered, too, why it is that when European ladies wear

Japanese clothes, or array themselves as "Japanese geisha," they

invariably make the most glaring errors—wear elaborately embroidered

kimonos,

stick many long pins in their hair, tie their sashes in front,

and, in short, make themselves resemble neither geisha nor ladies,

but

public women of the yoshiwara.

Neither Japanese ladies nor geisha

wear

embroidered kimonos

; they never wear a halo of long pins in their

hair, nor do they tie their sashes in front. These things are the

badges of prostitution.

The geisha

is an entertainer.

She is trained from childhood in the arts of music, dancing, singing,

story-telling, conversation, and repartee. No Japanese dinner in native

style is ever given without attendant geisha. There is

usually one

geisha at

least to every guest. Theirs is the mission to see that the

guests are never for a moment dull; to ply the saké

bottles and watch

the cups, lest for a moment they should be aught but full; and at

appropriate intervals during the meal to enliven the diners with music

and dancing. Compared with a high-class native dinner in Japan the

orthodox European one is the stifFest, slowest social function

imaginable.

The geisha,

too, is in great request for

boating and picnic parties, and no company of merry-makers intent on a

spree—-such as the opening of the Sumida River at Tokyo, or a visit to

the Gifu cormorant-fishing—would dream of going without geisha as

companions. Whenever two or three jovial spirits are gathered together

for an evening's fun at some tea-house a call is made for geisha to

furnish the music and to liven matters with their wit and songs. Apart

from the unique social place she fills, the geisha is simply a

woman—neither stronger nor weaker than others of her sex the world

over, exposed to the same temptations.

An author who has devoted a volume to an

exposé

of a liaison

he formed

with a Nagasaki fille

de joie

has done much to harm the Japanese woman

in the eyes of the world; but other writers have equally, though less

seriously, misrepresented her in the "pidgin English" they have made

her speak. A Japanese woman may speak broken English, but "pidgin

English" never. She does not say "velly" for "very"; and for "like"

she does not say "likee" but "rike.'' The Chinese replace ''r" with

"l'' when speaking English, but not so the Japanese, for

their alphabet has no letter "l," whereas "r" is one of the

commonest sounds in the language. They therefore turn all our "l's"

into "r's" until they have learnt the unfamiliar sound.

Moreover, the Japanese girl does not suffix her English verbs with

"ee." She does not say "talkee," "walkee," "thinkee," "speakee,"

etc. She never talks this "pidgin" jargon of the Chinese ports, but

such English as she knows she speaks, perhaps brokenly, but very

prettily. English is now taught in every school, and taught correctly;

when one reads, therefore, this gibberish, as samples of a Japanese

girl's conversation, one may well be pardoned for wondering whether the

writer of it has ever seen Japan.

To those who would

really wish to know this dainty creature—the Japanese lady—who would

learn of the whole order of her life, from the time she wears her

swaddling clothes to the day she is wrapped in her shroud; who would

see the pretty Japanese child grow into happy girlhood, and the happy

girl gradually develop into sweet budding womanhood; who would see

this sweet woman grow sweeter and more lovable still as she becomes a

mother; who would see this gentle mother rear her family, and each day

be more

honoured and respected until she attains the height of her fondest

ambition and power as a grandmother; to those who would, in fact,

follow the Japanese woman from the cradle to the grave,—I would say go

at once to your bookseller and order Miss A. M. Bacon's work, Japanese

Girls and Women, for in the pages of this delightful

volume you will

find so charming an account of family life in the Land of the Rising

Sun that, when you have read it, you will know the Japanese lady far

more intimately than you would be ever likely to by travelling in the

land.

Miss Bacon's opportunity was unique, and

fortunately she was more than competent to embrace it to the full. Her

book is a classic; for a similar chance can never come to any one

again. Japan is rapidly changing, and the Japanese girl of to-morrow

will be quite a different creature from the Japanese girl Miss Bacon

wrote of yesterday.

The traveller to far Japan must not

expect to find home life there an open book. A Japanese visiting

England, furnished with good letters of introduction, would be welcomed

with open-hearted hospitality into the family circle of his newly-found

acquaintance; and every member of the household would do his or her

best to contribute to the enjoyment of the guest. After a round of such

visits the traveller from the East would be well qualified, on his

return home, to write about the home life of the English lady.

But how different is the case of the

European bearing letters to the

Japanese! The very most he can expect is to be invited to some

club—perhaps a Japanese dinner, with its accompaniment of

geisha-dancing,

may be arranged in his honour at the Maple Club—or in

some exceptional cases he may be invited to see the house and gardens

of his host. In still more exceptional

instances he may be presented to the wife and daughters; but he will

never be invited to stay at his host's house, and, for the time being,

become, as it were, a member of the family. How, then, can the passing

globe-trotter ever hope to see the Japanese lady in her true

perspective, when foreign residents, who have passed their lives in

Japan, admit that even they have only formed their estimate by a series

of fortunate glimpses, few and far between?

Owing to

the nature of the mission that took me on my last journey to Japan—as a

correspondent during the war with Russia—I had the honour of meeting

more than one Japanese lady, and the great good-fortune to see certain

phases of the character of the women of Japan, which, up to that time,

the world had never suspected they possessed. For what I then saw I

shall revere and honour the Japanese woman always, for she stood

revealed to me in all those qualities that men mostly esteem in the

opposite sex. She was sagacious, strong, and self-reliant, yet gentle,

compassionate, and sweet—a very ministering angel of forgiveness,

tenderness, and mercy.

I cannot, in the limits of this

essay, give more than a few vignettes of this brave yet most feminine

of women; but I hope to show that she is something more than a "pretty

butterfly," *1 as she is generally thought to be by those who do

not know her. When duty calls, there is no woman in the world who obeys

more readily and capably; and the best of Japanese manhood respects

her as truly as any other woman in the world is respected, even though

he loves her less demonstratively.

Close observation, during three years of travel in this land, has

clearly shown me, too, that the women of the Japanese peasant and

poorer classes are accorded such courtesy from the opposite sex as is

quite undreamt of by women of the corresponding classes in Europe.

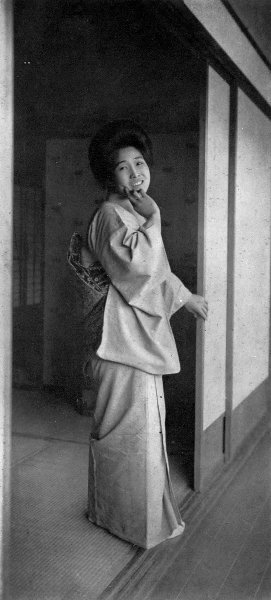

A GEISHA DANCING

Would that one could speak as

warmly of all Japanese men as of their

mothers, wives, and daughters! My own experience, however, fully

corroborates that of Professor Chamberlain. Writing of Japanese women,

he says: "How many times have we not heard European ladies go into

ecstasies over them, and marvel how they could ever be of the same race

as the men! And closer acquaintance does but confirm such views."

Shortly after my arrival in Yokohama, in

the summer of 1904, one gloomy

day—when drenching rain was falling from leaden skies and every street

was full of puddles—as my rikisha

suddenly turned into Asaki-machi we

found our way blocked by a crowd that lined both sides of the street,

and in the midst of the throng a long line of people wended their way

in silence that was only broken now and then by the depressing and

discordant strains of a native brass-band.

I asked Tomi,

my kuramaya,

what it all meant, and he replied, "One soldier make kill

Manchuria, now make bury." Then I understood that it was only the

funeral train of a soldier who had died for his country. I had thought

for a moment that surely it must be the Emperor, or at least some other

royal personage, whom the crowd awaited, and that these people,

tramping in the rain and mud, were latecomers, plodding along the route

in the hope of securing a vantage-point farther down the line. But no,

they were there to see neither royalty nor the owner of a title;

they had come out in the drizzling rain to pay a last tribute of

respect to a simple soldier—a private of the rank and file, who had

died fighting for his country.

I had arrived just as the

cortège

began, and a number of Shinto priests were passing as we

stopped. Following them came several hundred carpenters, tinsmiths,

jobbers, carvers, and other skilled labourers, each wearing on his back

a broad design—the emblem of his craft. Then followed many hundreds of

schoolboys, in uniform, some in white, some in red, and some in blue;

then, solemnly and sedately, each protected by an Inverness coat and

wide umbrella, came fully five hundred of the employees of merchants of

the town, and these were closely followed by a quarter of a mile of

ladies, walking four abreast, who had braved the elements to tread many

weary miles through the muddy streets, all because a simple private,

who had once lived in Yokohama, had given his life for his country!

As the slight little dames pattered by

on their quaint high geta *2 I

could not help thinking that each one was doing her duty as faithfully

and well as the soldiers who went out to die. These little delicate

women could not go out to fight, and all of them were not needed in the

hospitals; but each had in her breast the qualities that breed the

soldier, and so they had not hesitated to come out in their hundreds to

walk many weary miles, through muddy streets in the drenching rain, in

order that a soldier, who had died in doing his duty, might be shown a

last tribute of respect. And as the funeral procession wound on, the

same features occurred again and again: schoolboys, school-girls,

mechanics, clerks, merchants, ladies, priests, and little girls in

white, dressed as Red Cross nurses. There

were also many hundreds of men in various uniforms; these were the

residents of certain streets who had formed into guilds and adopted a

distinctive uniform of their own.

As the minutes passed

by, half an hour changed to an hour, but still the people came and

passed along—old and young, man and boy, wife and maid—and the colour

of the long procession changed from black to white, from white to grey,

and to yellow, and red, and blue; and ever and anon there was a dash

of every hue as tiny girls in gay kimonos

toddled along under great

oiled-paper umbrellas held by their parents. Tired of waiting for the

end, I left, for after watching for more than an hour, the tail of the

procession seemed as far off as ever.

There was no

corpse borne at the head of the mourners, but only a few relics of the

deceased hero, and his larynx, *3 which had been saved from his funeral

pyre in Manchuria.

The whole spectacle was at thattime

a most significant one, for it plainly showed that, if need be, Japan

could rely upon not only every man and boy in the land, but every woman

and girl as well, to help her win the fray.

I witnessed

many sad scenes in those days when I was waiting in Japan for

permission to go to the Front. Many a time I saw a soldier bidding his

last good-byes to wife and mother before embarking for the war; but I

seldom saw any tears. Often there were even smiles, for in Japan the

smile is a mask which hides the agony of the heart. The women exhibited

a front so firm and unquailing as it seemed well-nigh impossible such

gentle little creatures could show. And there were no caresses at

parting, but only many and many a bow, and sweet

oft-echoed sayonara. *4 And as, the farewell over, the little wife and

mother turned back to her husbandless home, if nobody cared to know of

the fear and dread that lay deep in her bosom, certainly nobody would

ever divine it from any betrayal in her features; for her face, like

that of her husband, who smilingly went forth perhaps to die, was a

mask, a lie, a disguise born only of blood trained for centuries in the

mastery of the feelings.

I saw tears sometimes, however,

for every Japanese woman is not a Spartan, and the poorer people cannot

always control themselves on such occasions as can the better-educated

classes. During the war, correspondents often wrote that "Japanese

women never cry," but I have seen women of the lower classes weeping

bitterly when parting from their husbands. Not all could restrain their

feelings as could those of better blood, but I did not often see such

human weakness shown.

The self-control of the Japanese

women, when troops were leaving for the Front, was misunderstood by

many foreigners. They were called cold, and lacking in sympathy, and

indifferent; but this was far, far from the truth, for they are full

of such feminine instincts as sympathy and fellow-feeling. On such

occasions as a husband going to the war it is a point of almost honour

to control oneself, but I have often seen an act of kindness bring

tears to Japanese eyes, and I have seen a whole theatre-full of

people—women, and children, and men too—sniffling and sobbing audibly

as a

touching tragedy was being acted with masterly skill. No! the Japanese

woman's heart is not hard and cold; it is full of sympathy, and

tenderness, and pity.

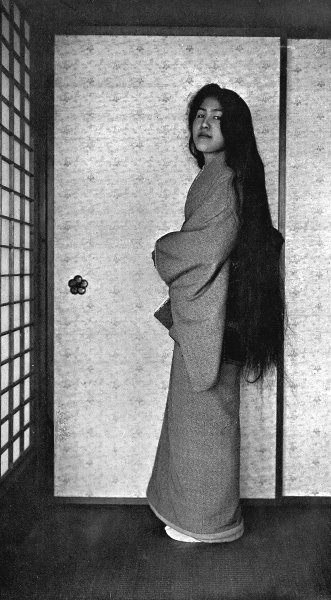

A MAID OF FAIR JAPAN

The Japanese smile, too, which is so often belied by the heart, takes

long to understand, but when one knows what it often means, the very

soul is sometimes wrung to see it.

A Japanese friend with whom I travelled

for many weeks was constantly

talking to me of his sister, to whom he was deeply attached. He showed

me her picture—she was a lovely girl, just turned eighteen—and told me

so much of the happy days he and she had spent together that I almost

seemed to know her. Her parents had taken her to Dzushi, a seaside

resort for consumptives, for the dread scourge of Japan had settled on

this sweet young life. One day when we arrived in Kyoto, after a long

tour in the country, a letter was placed in his hands as we entered our

hotel. He tore it open and read it, and then turning to me, with a

smile that I shall never forget, laughed, "Ha, ha, my sister is dead

already!"

As his features assumed the ghastly

mask,

and his tongue uttered the cold-blooded words, a chill of repulsion

swept over me; then my soul went out to him in sympathy, for, though

there was not a quiver of an eyelash, I knew that the smile was a lie,

and that his heart was almost breaking at the unexpected blow. He went

at once to his room, and I saw him no more that day—for I respected his

evident desire to be alone—but friendship warmed towards him, as I

knew that the tears he refused to show in public were shed for many

bitter hours in the solitude of his chamber.

During the

American war with Spain there was a Red Cross Society formed at San

Francisco, and American ladies vied with each other, during the few

hours they snatched each week from their "pink teas" and other social

functions, in making abdominal belts to ward off the dysentery and

fever of the Philippines. One of these belts was presented to each

soldier, who promptly applied it to the use of cleaning his rifle.

There was much talk about "Red Cross." The word was in every one's

mouth, yet I never knew what it could really mean until I reached

Japan. Soon after I arrived in Tokyo I saw a vast room, where a number

of ladies—the highest in the land, many of them ladies of title, and

led by that most gracious and kindly lady of all, the wife of the

Commander-in-Chief, the Marchioness Oyama—worked each day and every day

for months, from early morning till evening, making warm woollen and

flannel clothing, with their own fair fingers, to be sent out to

Manchuria in readiness for the rigorous winter. There were scores of

such gatherings at work daily all over Japan. There was not a lady in

the land who did not feel that she could do something to help, and

every soldier who was made warm and comfortable in the severe winter of

1904 was worth three half-frozen men. But the ladies did more than work

with their needles: they threw themselves into hospital work with a

will worthy of so great a cause, and when the little band of American

nurses arrived in Japan they found the Japanese nurses already knew as

much as they themselves.

Desiring to observe the working

of the Japanese Red Cross organisation, I secured permission from the

War Department to visit the Reserve Hospitals at Hiroshima.

Hiroshima, capital of the province of

Aki, a beautifully-situated town

near the mouth of the Ota River, which flows into the Inland Sea, ranks

as the seventh city of the Mikado's Empire—being populated by 130,000

souls.

Although on the main line of the Sanyo Railway—which, for almost its

entire length, from Kobe to Shimonoseki, passes

through some of the fairest scenery in the land—Hiroshima does not

appear in the usual tourist's itinerary, as its sights are few,

consisting, all told, of a fine old Daimyo garden and an ancient feudal

castle, of

which little remains but the keep. Moreover, the city's attractions,

such as they are, are entirely overshadowed by those of the adjacent

lovely island, Miyajima, where the globe-trotter, weary of sightseeing,

may rest and loaf himself back to activity again in as peaceful a spot

as can be found in all the wide world.

But Hiroshima,

from the standpoint of its relation to the war with Russia, stood in

importance second only to Tokyo; it was practically the rear of the

army as far as the wounded were concerned, for they were sent back

there from the Front in a week, with their first-aid bandages still on.

It was not till I arrived at this place

that I began to realise

something of the real horrors of war, and the awfulness of the terrible

task on which Japan was engaged. In the time that I spent in the

hospitals I learnt, too, more than I could otherwise have known in a

lifetime about Japanese women; for I saw there what a great and

glorious part women can play in time of war.

On my

arrival I found the town swarming with soldiers. Indeed, it is no

exaggeration to say that every fifth person met on the streets wore the

uniform of the Japanese army, and in some of the streets there were

fifty soldiers to each civilian. Every barrack was full, and fresh

troops arrived daily to be billeted on the inhabitants. The streets

echoed with the tramp of armed men, marching to embark for the Front at

the near-by port of Ujina; the clink of the trooper's spurs, and the

clank of his steel scabbard, mingled with the sound of horses' hoofs,

the clatter of innumerable transport carts, and the metallic noise of

field-guns rumbling and crunching on the macadam.

The Japanese inn at which I put up abutted on the river; indeed, the

balcony hung over it, for at high tide I could look

into the clear green water below. Hardly had I entered my room when a

number of sampans,

being rapidly yuloed

up on the flood tide, attracted

my attention, from the nature of the burden which they bore. Besides

the boatman, each craft carried several figures, and these, as a single

glance revealed, were soldiers—but soldiers who no longer stood with

the spic-and-span aspect of the warrior outward-bound; soldiers who no

longer carried arms; soldiers who no longer held their heads erect,

looking the world in the face with steady, unflinching gaze. They were

soldiers who sat or lay on soft red blankets; whose forms were bent

and whose limbs were bandaged; whose faces were pale and drawn with

suflfering; whose uniforms were stained with weather and dirt, and the

deeper, lasting dye of blood; or who wore long white kimonos with

crosses of brilliant red.

It was a sight to stir the

blood, for these were men fresh from the field of battle—war-stained

heroes whose wounds were not yet ten days old. They were men who would

bear to the grave the glorious marks of victory; men who had fought

the fight; men who had done their duty. They had come from Dalny,

Manchuria, in one of the hospital ships, which almost daily arrived at

the port of Ujina, and were being conveyed, thus, by water, almost to

the portals of the great Reserve Hospital.

I hurried to

the place of landing, a mile farther up the river, where a bank of

gleaming sand sloped to the emerald depths. Here were waiting, in the

grateful shade of the pine-trees, a number of native coolies, with

stretchers lying beside them. Soon the first sampan came into view, and

was gently beached on the sand. It contained four wounded officers, the

first to reach Japan from the battlefield at Liao Yang, where victory

was won at such terrible cost.

PRINKING UP FOR THE DAY

This was quickly followed by

many others, bearing officers or men. Some of the less severely wounded

were carried ashore on the backs of the coolies; whilst others, with

infinite care, were gently laid on stretchers, and borne to the gates

of the hospital, near by, where an officer stood and assigned the

cases, as they passed him, to certain wards, according to their nature

and severity.

For nearly three weeks I spent the

greater

part of each day in the various divisions of this hospital, where over

twenty thousand wounded soldiers were being cared for; and, having

later spent a week in the Russian prisoners' hospitals at Matsuyama, I

can truly say that, to friend and foe alike, the Japanese nurses were

veritable ministering angels of mercy. Their tender solicitude; their

quiet ways, as they moved quickly, yet like phantoms, about the wards;

their readiness and willingness to obey instantly the wishes of their

charges; their untiring energy and devotion; their patience and

earnestness; their courtesy to their patients, and their gentleness in

washing and bandaging them—all showed that these Japanese ladies, who

had responded so nobly and whole-heartedly to the call of duty and

humanity, were as instinct with all the finest virtues of their sex as

any women in the world.

The whole organisation of the

Red Cross, in which the Japanese woman played so great a part, had,

like that of the army itself, been so thoroughly worked out in every

detail that it ran with the smoothness of a well-oiled machine.

Everybody went about his or her business quickly, quietly, and

unostentatiously, from the highest officials downwards to the

stretcher-bearers. There was never at any time any rush, or bustle, or

noise, even when hundreds of poor shattered fellows were coming in

daily, as they did when I was there, from the battlefield of Liao-Yang.

Many of the wounded, also, came from the

vicinity of Port Arthur, and

some of these were in the most shocking condition of filth. They told

me they had not had a wash for over four months, for water was scarce

on the barren hills of Liao Tung. This alone was a terrible hardship

for men hitherto accustomed to have a hot bath every evening of their

lives. So thick was the coating of dirt on these men, and so callous

the skin on their legs, that only repeated hot baths, followed by

scraping the skin with a sharp-edged piece of wood for many days, could

bring the limbs back to their normal condition. Some of these poor

fellows were not only seriously wounded but had beri-beri as well. They

therefore needed an amount of personal attention which can be more

easily imagined than described, and over them Japanese ladies would

work tenderly and assiduously for days.

Nothing

impressed me more than the stoical manner in which the wounded bore

their injuries; and all seemed bright and cheerful and anxious to

return to the Front as soon as possible. I noticed, however, one man

who hid his face continually in the pillow and never talked or smiled.

On asking his nurse the reason, she told me that his arm had been badly

and permanently injured in an accident when he was assisting in getting

a field-gun up one of the Manchurian hills. He felt that, whilst his

comrades would bear to the grave the glorious marks of battle, there

was no honour attached to his wound, and when I questioned him

personally he told me that death at the hands of the enemy would have

been better than such lasting disgrace as he considered must now be

his. Nothing would comfort the poor fellow, or convince him that his

wound was as honourable as those of his comrades.

Sometimes I was permitted to watch the surgeons and nurses at work in

the operating rooms, and I often saw the bandages removed from injuries

so terrible as to make my blood

run cold. More than once, too, I stood beside poor wasted heroes,

shaking at their last gasp, but I never saw a Japanese soldier give way

to tears, or heard a conscious man utter a groan.

Every

week a messenger came from the Emperor to speak a few encouraging words

to each individual patient, and present him with a small sum of money

for the purchase of cigarettes, or some other little luxury. Ladies of

high degree would also constantly come from the capital to inspect the

various wards and cheer the inmates by their presence.

One day I went to the station to inspect

a hospital train in which a

number of convalescents were to be sent to a hot-spring resort until

fully recovered. Whilst I was standing on the platform a train full ot

Russian prisoners drew up to the platform. Every man in the train who

was not playing a concertina was shouting or singing himself hoarse

with joy at having got away from the war. The station was a

pandemonium. Just then a train approached from the opposite direction.

It was filled with Japanese troops, singing with equal joy because they

were off to the Front. No sooner had Russians and Japanese caught sight

of each other than half a dozen heads were thrust from every window,

and every man burst into cheers—the Russians shouting the Japanese cry

of "Banzai''

as heartily as the Japanese. The moment the train came

to a standstill the Japs were out of their carriages, and, running over

to the unfortunate (?) captives, showered cigarettes upon them, and

everything eatable they possessed, whilst the Russians wrung their

kindly adversaries' hands, and even tried to kiss their faces. It was

one of the most human scenes I have ever witnessed.

I saw many pathetic scenes, too, during those weeks at Hiroshima; but

I think the incident that touched me deepest was

when the pupils of a primary school for little Japanese girls visited

the principal wards. There were perhaps fifty in all, in the care of

their lady teachers, and as they tripped silently, in their soft white

socks, into the ward, where I was sitting by the beside of one of my

favourites, they all courteously bowed several times to the patients on

one side, then several times to the patients on the other. Every

soldier who could, returned the courtesy, and those who could neither

sit nor stand inclined their heads or raised their hands to the salute.

The principal lady teacher, in sweet,

gentle tones, then quietly

addressed the men, telling them how great was the honour that she and

her pupils felt to have the privilege of visiting so many gallant

soldiers who had helped to gain a glorious victory for Japan. Here the

fifty little heads all bowed in mute approval of their teacher's words,

and she went on to say that she hoped every soldier would soon be well,

and perhaps able to fight again, but that those who had been too

severely wounded to return to the Front would always be honoured for

the part that they had played in the war. The childish heads were

ducked, with one accord, again.

Turning to the little

girls, who all stood meekly with eyes upon the ground, the teacher then

addressed her charges, reciting briefly the story of the great battle

in which these poor fellows had fought, and how it was won, and how

bravely they had done their duty. She continued that it would be a

proud moment for their parents when these, their sons, returned to

their homes, bearing the honourable scars of war. No woman could have a

higher ambition than to be the mother of sons to fight for Japan, and

she hoped that when these little girls grew up, and had sons of their

own, they would teach them to be as brave and loyal subjects of the

Emperor as the soldiers now lying maimed before them.

EN

DÉSHABILLÉ

EN

DÉSHABILLÉ

The tiny lassies

here all bowed again in silent resolution, and then, with several

parting bows to right and left, they proceeded to another ward.

To me the incident was a stirring

object-lesson of how Japan loses no

opportunities of educating her children. Those little girls would

remember all their lives what they saw that day; and the words of

their school-mistress, I have no doubt, sank deep into each of those

childish souls. As years pass by, and those little girls become

mothers, the exhortation of that soft-voiced teacher, made under such

impressive circumstances, will sound again in their ears; and sons of

Japan, as yet unborn, will grow up to be better and braver men because

of words their mothers listened to when they were little more than

babies themselves.

At Matsuyama the Russians could not

sound the praises of their gentle Japanese nurses loud enough. The

looks with which the fallen followed every movement of their little

guardians told a plain and simple tale, and more than one gallant

fellow, when he left his bed, was pierced by an arrow that wounded him

far deeper than the bullet which had laid him low.

Never

in all history did foeman have a kinder and more generous adversary

than did Russia in the recent struggle, and never did women of any land

play a nobler and more tender part than did the women of Japan.

It must not be thought that because

Hiroshima was a hospital town that

it was necessarily a doleful place. Like most garrison towns, it was

gay. Indeed it was the gayest of the gay. As I have already said, my

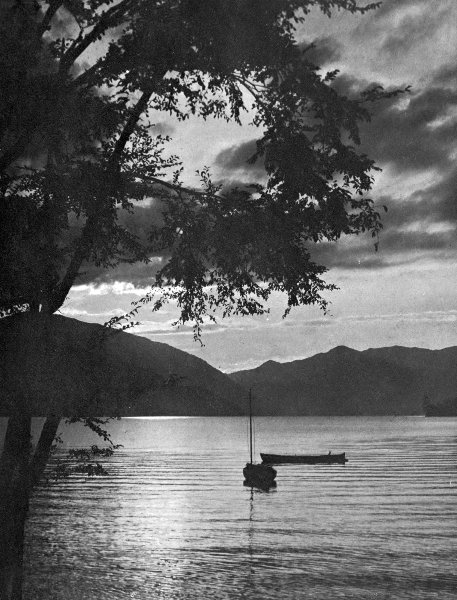

hotel bordered on the river—one of the five streams that form the delta

of the beautiful Ota-gawa. On either side of it were other hotels,

restaurants, and tea-houses; and on the opposite bank of the river

similar conditions

obtained. These places were all crowded, according to their class, with

military officers or soldiers, billeted there for a day or two prior to

their departure for the Front.

As soon as the fall of

night settled on the clear green waters, the sound of the samisen rang

out from every house beside the moonlit river. As surely, too, as the

light on the paper shoji

changed from that of day without to that of

lamps within, the plaintive cadence of the geisha's song

wailed out on

the evening air.

Night after night I listened to her

songs of revelry, of love, and of despair. There was something weirdly

pathetic about her often sorrowful lay—for the geisha is at her best

when singing of some stirring incident that lives for ever in history.

One night, as a singularly beautiful

voice broke on the night air, the

samisens and other sounds were silenced, one by one, till naught but

this one woman's voice could be heard. Every window was thrown open,

and every reveller on each side of the river crowded to the balconies

to listen, for the singer was one of the most famous in Japan, and the

song she had chosen was the Ballad of Dan-no-ura.

*5

Inspired by the impressive silence,

impelled by her art, she sang with

magic power the terrible story. In accents wondrously sweet she told of

Tokiwa's pleading for her mother and her children, and in piteous tones

of the dishonour of the famous beauty. Then in tragic crescendo she

sang of Yoritomo's lust of vengeance for his mother's ruin; and in a

frenzy of passion of the great Minamoto leader's resolve to stamp the

Taira clan from off the earth. She sang of how the tide of battle

waged, first this way, then that, in the great historic conflict, till

it ended in the complete extermination of the rival clan—even to the

slaughter of women and

children—and over the sadness of the final lines of suffering and death

her voice grew infinitely tender and pathetic, culminating in an

outburst of vehement sobs.

On the balcony, listening

beside me, there were several Japanese officers, and the eyes of more

than one were dimmed, for the story is the most famous and bloody in

Japanese annals—one that will live in the hearts of the people when the

war with Russia is forgotten.

As the sweet voice of the

singer ceased only her sobs for some moments broke the silence; then

from every balcony and window on both sides of the river there burst

forth a storm of applause and loud shouts of approbation.

At Hiroshima it was always this dainty

creature, the geisha,

who made

merry the last evenings of the officers ere they went forth to the war

; and she was always the last to cheer them on their way, pledging

them, in tiny sips of saké,

health, victory, and a safe return. Truly

it is almost as hard to imagine how Japan could survive without the

geisha as

without the army itself.

That the sterling

qualities of the Japanese women were appreciated by the officers of the

army I had daily evidence during the time that I was attached to the

First Division in Manchuria. One of the first questions asked me by

every officer whose acquaintance I made was, "What do you think of the

Japanese women?" and the following incidents serve to show something

of the regard in which they were held by the leaders.

On

one occasion, at Mukden, when I went to pay my respects to the

Commander-in-Chief, and to General Baron Kodama, I met the latter

outside his head-quarters—a Mandarin's yamen. *6

Kodama was a handsome man, rather

American than Japanese in appearance, with a deeply-bronzed face and a

pair of dark-brown eyes which were always sparkling with the love of

fun. He was the most celebrated wit in Japan, and even during the heat

of a great battle his jokes, I was told, never ceased. I had previously

met him at Tokyo—the day before the departure of the General Staff for

the Front. I was in his drawing-room, when General Baron Terauchi, the

Minister of War, called, with several other exalted officers. Instead

of the conversation being of a serious turn (seeing that such momentous

events were portending), it was, on the contrary, of the most jovial

nature, and the impression I shall always have of General Kodama on

that occasion was seeing him leaning back in his chair, roaring with

laughter at the fit of the War Minister's riding-breeches.

When I met him in Mukden he at once

invited me to enter his house, and

holding aside a bamboo portiere that hung in the doorway, and pointing

ahead, said, "There! what do you think of that?" in Japanese. I

looked, and saw a large kakemono *7 of a Japanese girl, painted in

modern style and nearly life-size. I congratulated him on being so good

a connoisseur of feminine beauty, whereupon he laughed merrily, saying,

"You see I'm not very lonely here with such a lovely girl to look at.

Beppin-San des, ne?" ("Isn't she a daisy?") Then he laughed again

more merrily than ever.

I found his apartments

luxuriously furnished in Chinese style. There was an immense map of a

part of Manchuria stretched out on the kang. *8

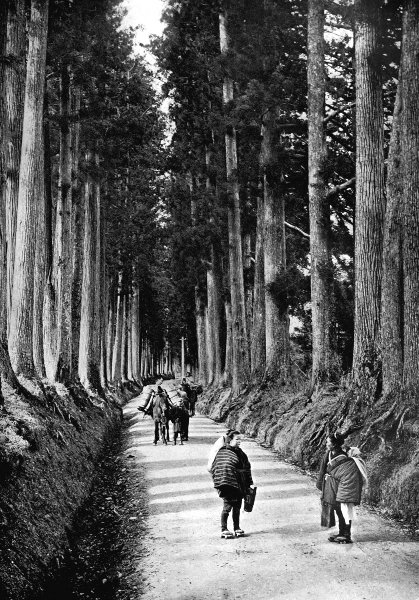

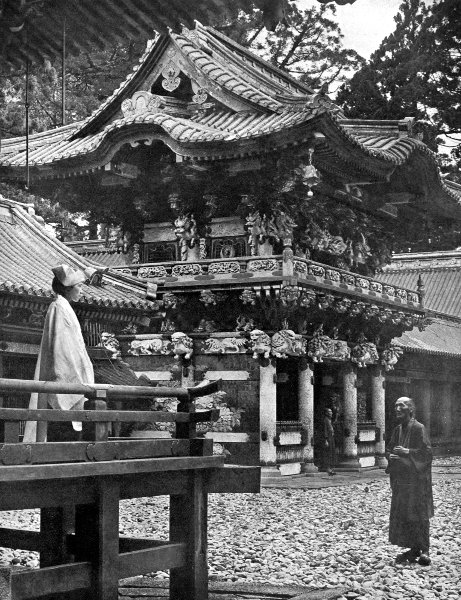

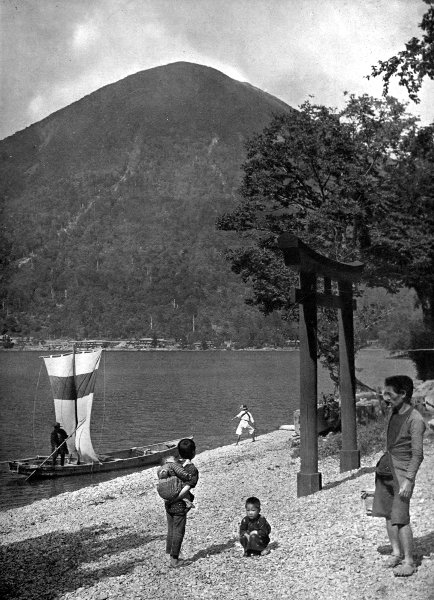

JAPANESE LADIES GOING TO THE SHRINES, NIKKO

This

map was a captured Russian one, so he informed me, and was marked all

over with pegs, denoting the dispositions of the troops. What, however,

most attracted my attention was a tall, slender Chinese table of

Blackwood—perhaps ten inches square and three feet high—on which

stood the most beautiful doll I have ever seen. The little figure was

about twelve inches tall, and marvellously life-like. It was dressed in

an exquisite mauve silk kimono,

with a rich gold brocade obi

; and

every detail of a Japanese lady's toilet was carefully worked out, even

to a tiny jewelled obi-domi *9 and the pin in her hair. It was, in fact,

a perfect miniature of a Japanese lady, and a work of high art. "She

is my mascot," said this great General, who was known as "the brain of

the Japanese Army." "She is my mascot, and goes with me wherever I go.

She has brought me much good luck." Such was General Kodama's tribute

to the women of his land.

As I heard his words I thought

how great was the privilege I was enjoying in thus seeing into the

heart of this gallant soldier—one of the greatest of modern history.

And I thought, too, that if the days of chivalry be dead elsewhere,

they still live in Japan, for surely never did knight in the days of

old take the field with a fairer, nobler emblem than the image of his

lady.

A few days after this incident I was

sitting next

to General Kuroki—Commander of the First Division—at a General Staff

dinner at the Front. General Kuroki is one of the samurai of the old

days—the knights of feudal Japan—and the following episode will show

something of the mould in which his gallant soul is cast.

He spoke no English, but conversation

was made through the medium of

that lightning interpreter, Captain Okada, who translated each sentence

the moment it was spoken.

Having a fair working

smattering of Japanese, I mustered up courage, after a glass or two of

wine, to address the General in his native tongue. I was equal to the

following simple sentence, and voiced it, "Anata sama Eikoku no

kotoba hanashimasen ka?" which means, "Does not your

honourable self

speak English?" It was simply a plain, unpolished speech, but the

effect on General Kuroki was electrical. Turning to me with his eyes

opened wide and his brow puckered up, he replied, "Eikoku no kotoba

hanashimasen; anata wa Nihon no kotoba yoku wakarimas, so ja arimasen

ka?" "I do not speak English; you understand Japanese

well; is it

not so?"

I replied that I only knew very little

indeed, and then asked General Kuroki what part of the country he came

from. He replied, "Satsuma."

I told him I had read that Satsuma had

always been a famous province for producing fighting men.

"You have studied Japanese history,

then?'' he answered.

"Yes, a little, and I have found it

exceedingly interesting, and not

unlike our own. Your feudal days are not fifty years old, whereas ours

are five hundred; that is the principal difference," I replied.

From this we got on to various phases of

Japanese history, and I

mentioned the bombardment of the Kagoshima forts by the British under

Admiral Kuper in 1863. Captain Okada had stepped in as interpreter,

never hesitating for a word, as the conversation had got beyond my

linguistic powers after the few sentences which had served to start it.

The old General's face became a study, and his eyes a blaze of light,

as he replied, "Yes, I was there, I was there at the time. I was a boy

of eighteen, and helped to serve one of our guns!"

So excited did he become as he began to

tell me of this affair, and

warmed up to it, that he made a plan on the table—using glasses and

plates, and anything that was handy, to mark the positions of the

various forts—whilst the staff officers crowded round to see. A large

ornamental vase on the table was the island of Sakura-jima, and a

number of wine-glasses were used to show the position of Admiral

Kuper's ships.

He told me, what I had already read,

that

a fierce hurricane raged throughout the day, and that some of the ships

had to cut their cables and put to sea; that the captain and sixty

members of the crew were slain on the flagship, and that although the

squadron succeeded in setting fire to the town and dismantling the

forts, they departed much the worse from the effects of the Japanese

guns and the ravages of the storm.

After a long pause

the old General continued: "Those were dark days for Japan—when all

the land was rent with strife; when we were yet in ignorance of what

would be the outcome of it all; when we seemed beset on all sides with

enemies, and England seemed the most terrible of all. How different it

all is now! How different it all is now! England is our warmest

friend, and has taught us most of what has brought us success. How

could we ever foresee at that time that the trials, through which we

were. passing, were but the fire heating the steel which the events of

later years have tempered?"

It was a beautiful speech,

and beautifully put. "The tempered steel!'' That is Japan to

perfection. Steel tempered when the red has run down to a dull cherry

glow, plunged for an instant in cold water, held until the colour has

changed to a brilliant straw yellow, and then plunged again. Japan is

now as steel tempered thus, and steel treated in this way is tougher

than any other.

It was one of the most interesting hours

of my life when that old

Satsuma samurai

stepped out from the pages of Japanese feudal history;

and, with eyes sparkling and hands illustrating on the table, told me

of that day which marks one of the deepest of England's injustices, and

the darkest stain on her early dealings with Japan. The staff officers

were as interested as I in their Chiefs story, and when he had

finished, the impressive silence showed how deeply all were stirred.

Immediately afterwards we were engaged

in a discussion on the

remarkable qualities of the Japanese soldier—his indifference to

hardship, his endurance and bravery, and what he had accomplished.

General Kuroki after a time spoke thus:

"When we speak of the

achievements of the Japanese soldier, we must not forget that it is not

the men of Japan who are altogether responsible for these deeds. If our

men had not been trained by their mothers in the teachings of Bushido—that

everything must be sacrificed on the altar of duty and

honour—they could not have done what they have to-day. The Japanese

women are very gentle and very quiet and unassuming—we hope they may

never change—but they are very brave, and the courage of our soldiers

is largely due to the training they received, as little children, from

their mothers. The women of a land play a great part in its history,

and no nation can ever become really great unless its women are before

all things courageous, yet gentle and modest. Japan owes as much to her

women as her soldiers.''

As I listened to this gallant

tribute of the old General, spoken in such a soft voice, my vision flew

back to Japan. The weeks I had spent in the great Hiroshima hospital,

when many hundreds of poor fellows, shattered by shot and shell, were

being brought in daily,

passed in review before me.

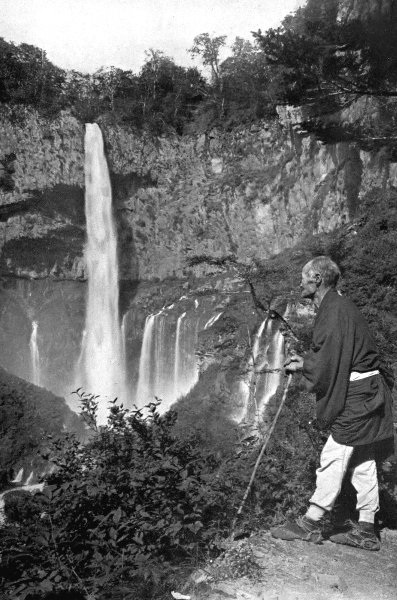

DECEMBER IN JAPAN

I saw again those gentle little angels in

white flitting noiselessly about amongst the beds. I saw them rapidly,

yet tenderly, ministering to the stricken, with kindly glances and soft

words, as their wondrous fingers removed and replaced dressings with

marvellous dexterity. I saw fragile little women standing by, unmoved,

whilst the most terrible operations were being performed, and I saw

them kneeling at the bedsides and stroking the brows of poor fellows

whose souls were going to rest. I saw, too, those gatherings of

ladies—the very noblest in the land—diligently working, day after day,

making warm clothing for the soldiers at the front; I saw again those

tiny school-girls, being led by their teachers through the wards of the

hospital, and being exhorted to remember, when they became mothers, to

bring their sons up as brave and fearless as the soldiers who lay

maimed, before them, in their beds.

I thought of all

these things, and many more, and when at length General Fujii proudly

added to the words of General Kuroki, "Let us drink to the Japanese

women, for I think they are the best in all the world," I remembered

again that Lafcadio Hearn had said the same of them, and I knew that no

one who had seen what the women of Japan really were, and really could

do, could honestly affirm there were any better, or truer, or braver

women in any land on earth. And one and all of us, who drank the toast,

with all our hearts echoed General Kuroki's words, "We hope they may

never change."

One day I went to see the late Prince

Ito

at his home at Oiso in Japan, and, as he showed me round the gardens,

heard, from his own lips, something of how he and his friend Count

Enouye, as boys, stowed themselves on board an English ship bound for

Shanghai, where they transhipped and engaged as seamen before the mast,

and thus

reached the country which was to give them the knowledge they craved.

Whilst the two students were in London the feeling against foreigners

in Japan, which had for years been growing steadily stronger, broke out

into open rupture. Of the unfortunate incidents that occurred perhaps

the most deplorable was the one known as the "Richardson Affair,"

which was all the more regrettable because the foreigners concerned

were entirely to blame for having, by their foolish action, brought

their fate upon their own heads. It was this matter that brought about

the bombardment of Kagoshima in 1862, to which I have already referred.

Ito and Enouyé, who were

vassals of the Choshiu Daimyo, hurried home on

the first news of these things becoming known to them. But on their

return to Japan both these adventurous young men were looked upon as

traitors by their fellow-clansmen, and wherever they went they were in

peril of their lives.

On one occasion Enouyé was

murderously assaulted and left for dead, but fortunately recovered.

Ito, however, escaped uninjured, and owed his life to the resource and

bravery of a young girl in the house to which he fled. She hid him in a

secret cellar, to which the only entrance was through a door under one

of the mats on the floor. Replacing the mat over the door, the girl sat

upon it, and when the ruffians entered they found her quite unconcerned

and busy with her needlework. They closely questioned her, but she

denied all knowledge of the man they sought, so, after searching the

house, and finding no trace of their quarry, the would-be assassins

went their way.

This meeting of Prince Ito (he was at

that time an untitled samurai)

with the brave girl was the beginning of

a romance which brought the pair together till the

hand of another assassin parted them forty years later;

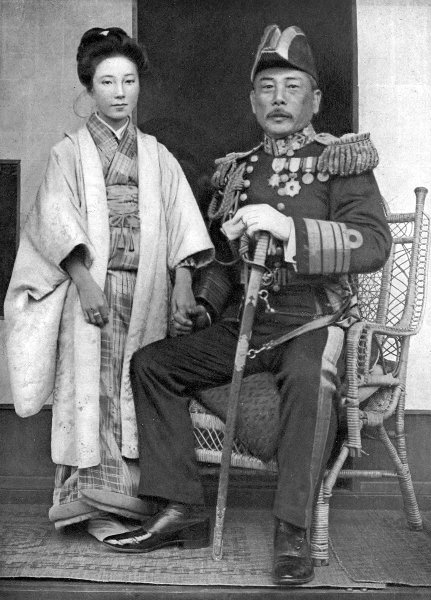

VICE-ADMIRAL KAMIMURA AND HIS DAUGHTER HOSHIKO

and when the

old statesman—who had filled almost every political post until he

reached the highest possible as Private Adviser to the

Emperor—presented me to the noble, courageous lady, who had saved his

life to become his life's companion, I knew that he had bestowed upon

me the greatest mark of courtesy that lay in his power, and I duly

esteemed the honour.

One of the most cherished memories

of my experiences during the war is a call I made upon Vice-Admiral

Kamimura on his return to Tokyo after his crushing defeat of the

Vladivostock cruiser squadron. I had the pleasure of meeting his wife

and Miss Hoshiko, his twelve-year-old daughter, and for an hour we sat

beside a charcoal brazier as the victorious admiral fought the battle

o'er again.

Then he went and donned his uniform, and

insisted on being photographed holding his little daughter's hand.

Afterwards we had another chat, and as I rose to take my leave, little

Hoshiko, with whom I had fallen head over ears in love, ran over to the

tokonoma,

and took from the vase, which stood in that recess of honour,

a spray of artificial flowers. With these she pattered back to me, and,

bowing her pretty head to the mats, begged me to accept them, whilst

her father proudly added, "She herself made them with her own hands."

I have those flowers now. Wild horses

could not tear them from me.

There is nothing that I brought from Japan that I cherish more, for to

me they are an emblem of the bravest and best of Japanese manhood, and

the very sweetest of Japanese childhood.

1) There is

nothing the Japanese girl, or woman, resents more than to be compared

to a butterfly. The cho-cho

does not appear to Japanese as we see it—a

beautiful summer insect—but as a fickle, restless creature that is ever

flitting about from flower to flower, never content to stay anywhere

long. The butterfly is, therefore, an emblem of inconstancy, and a

Japanese girl is hurt at being compared to one.

2) Wooden clogs.

3) The charred larynx was the only part of the body saved

from the fire and returned to the relatives.

4) Farewell.

5) See

page 348.

6) The mansion of a Chinese official.

7) Hanging picture.

8) A raised portion of the floor of a Chinese room which serves as a

bedstead, with flues running underneath its stone floor to warm it in

winter.

9) A small clasp, attached to a narrow silken band, that holds

the obi,

or sash, tightly in place.

CHAPTER XIII

THE HOUSE AND THE CHILDREN

About the tatami

and hihachi

of a Japanese household an entire volume

might be written, for on and around these important essentials of the

home revolves the whole domestic life of the nation. The tatami are the

mats which cover the floors of Japanese houses-, and the hihachi is a

receptacle for burning charcoal in—the fireplace of Japan.

The Japanese spends the greater part of

his life on tatami. He is born

on them, walks on them, sits on them, eats on them, sleeps on them, and

dies on them. They are at once the floor, the table, the chairs, and

the bedstead of Japan, and as such are deserving of more than passing

notice, for they reflect much of the character of the people with whose

life they come in such close daily contact.

Tatami

are

of many qualities, but of only one size—six feet by three. The area of

a room is therefore always estimated by the number it will contain:

thus an apartment measuring fifteen feet by twelve will hold ten mats,

and is called a "ten-mat room." Any Japanese hearing it described

thus, knows its size, because, whatever be the arrangement of the mats,

the floor will be covered by ten of them. Rooms are sometimes so small

as to have but three mats, or even two, whilst a little chamber of four

mats is quite common. Tatami

are two inches thick, made of rice-straw, tightly pressed and sewn,

with rectangular corners and edges,

and covered with closely-woven white matting made from rushes. The

six-foot sides are bound with broad tape—usually black, but sometimes

white—which laps over on to the surface, forming a border one inch

wide. Coloured matting such as is exported to America and Europe is not

used in Japan.

The floors of any well-kept Japanese

household present a scrupulously neat and clean appearance, and thus

they are a faithful mirror of the people who live on them. They are

also yielding and noiseless, especially as Japanese people never wear

boots in their houses. Boots are cast oflT at the threshold on entering

the house, and slippers are left on the polished wooden floor of the

passage outside the room. You can always tell by the number of pairs of

boots, or geta,

on a doorstep how many visitors are at a house, or by

the slippers outside a room how many people are within it.

In the best households the mats are

re-covered twice a year, so that

they are always fresh and white, with even a tinge of green in them;

or the covering may be turned, as both sides are alike, after six

months' use, and renewed completely at the end of the year. The matting

becomes yellow with age, and in poor households it is used until worn

out. No household, however, is so poor that it cannot afford tatami,

though some dispense with the tape binding. The arrangement of the mats

is altered occasionally, and the appearance of the room can be

completely changed by a fresh grouping of the straight black lines.

A ten-mat room is a very convenient and

even large-sized apartment in

middle-class houses; but in the houses of the wealthy and the nobility

rooms double this size are quite common, whilst rooms for entertaining

a number of guests may have as many as fifty mats or more. At a

Japanese inn that I stayed at in Gifu I was shown to an immense

apartment, the floor of which took no

less than seventy-eight mats to cover it, but my selection fell upon a

chamber of more modest dimensions.

If an apartment be

found too small for the use for which it is required, the sliding doors

(fusuma, or

karakami),

dividing it from the next apartment, can be

quickly removed, and thus two rooms are thrown into one. If the house

be a large one, a number of rooms can be opened up en suite in this

manner, should a large hall be required for entertaining purposes. The

karakami,

which are often adorned with paintings of landscapes or

figures, do not reach the ceiling of the room. They are six feet high,

and above them there are usually a few panels of open wood-carving,

which serve as a ventilator. These are called ramma. The sides of

the

.room facing the passage-way and open air are filled with sliding

screens, covered with rice paper. These are the shoji, and they

admit a

soft, diffused light into the room. Wooden shutters, called amado,

protect the shoji

at night-time or in wet weather.

The

principal part of a Japanese room is the tokonoma, a raised

recess at

one side, usually made out of beautifully grained woods. There the

single kakemono

(picture which rolls up like a scroll), which the room

contains, is displayed, with invariably some object of art beneath it,

such as a bronze or porcelain flower-vase, or a piece of carving, or a

dwarf tree in a dish.

The furnishings of a Japanese room

are simple. They consist of a hibachi,

and a cushion or two to sit on.

There are no tables, or chairs, or any of those aids to comfort that

help to make life bearable elsewhere. The tatami do duty for

all these

things. Conspicuous, therefore, in all this emptiness is the hibachi,

and there is much of interest about it.

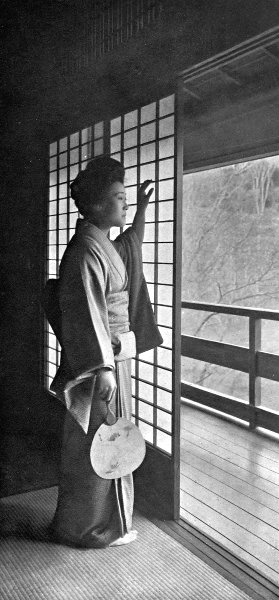

A STUDY BY THE SHOJI

The hibachi is of many

kinds. Sometimes it is a

curious stump; or gnarled excrescence of a tree; or a piece of wood

of beautiful grain; or it may be of stone, or earthenware, or

porcelain. More frequently still it is of brass or bronze, often

exquisitely carved. Its shape varies almost as much as its composition.

It may be round, or square, or oblong; or it may be polygonal in

design. Sometimes the hibachi

is built into a small chest, a foot high,

in one end of which there is a set of drawers, the top of which serves

for a table. This form, however, is only seen in the general domestic

living-room of a house or inn, and never in the guest-chambers or

private rooms.

The hibachi

is filled to within a few

inches of the brim with ash, which should be carefully heaped up into a

truncated cone, the top of which is hollowed a little. Into this

depression a few embers of glowing charcoal are placed. That, in a

nutshell, is the modus

operandi of the hibachi

; but about the

management of the charcoal and the ash, and the etiquette of the

hibachi in

general, much of interest may be said.

For

instance, in the best households the ash may be covered with several

inches of calcined oyster-shell, called kaki-bai, which is

a powder

white as driven snow; no common fuel is burnt in it, but cherry-wood

charcoal is used—so cleverly charred that even the grain of the bark is

intact. Each block is about two inches long, and in diameter according

to the size of the branch. It is sawed neatly and without any breaks.

Two or three of these little blocks, heated to a glow in the kitchen

fire, are carefully buried in the little crater, with the top of one

block just showing. These will burn without attention from dawn till

dark. The better the ash is heaped up round the charcoal the longer

will the latter burn, but if it be desired to increase the heat, with

consequent rapidity of consumption of the charcoal, a depression must

be formed in

the lip of the crater to allow the air to enter at the bottom of the

fire, and thus form a draught. Not only must the ash be evenly graded

into a cone, but there is a little serrated-edged brass scraper used

for this purpose. This has the effect of leaving the slopes of the

miniature volcano seamed with shallow furrows that converge towards the

summit.

The charcoal is managed with a pair of

brass or

bronze tongs, called hibashi,

often as delicately wrought as the

brazier itself. These are manipulated by the fingers of the right hand

in the same manner as chopsticks. At inns the common grade of charcoal

usually supplied requires much attention, as the cheaper the charcoal

the more rapidly it is consumed. Moreover, at inns one never sees

anything so expensive as oyster-shell ash, though I have occasionally

seen burnt lime used as a substitute.

It is a great

breach of etiquette to throw cigarette ends or anything into the

hibachi

which will make it smoke. A small receptacle is always provided

in the tabaco-bon *1 for this purpose. At inns, however, no such niceties

are observed, and after a meeting of several friends the hibachi

usually bristles with cigarette ends sticking in the ash. When the

party has dispersed the neisan

removes these, and each morning, before

renewing the charcoal, she carefully sifts the ash through a wire sieve

to separate all lumps, left from the previous day, and any foreign

substance that may be in it.

At high-class Japanese inns

the guest-room to which I have been shown has sometimes been of such

immaculate cleanliness that I have stood on the threshold hesitating to

enter it, for to tread such snowy mats with foreign socks instead of

soft white tabi seemed almost like a

sacrilege. The karakami

would be adorned with frescoes; the ceiling

made of beautifully-figured, unpolished wood, and the whole apartment

illumined by a flood of soft, mellow light that came through the paper

shoji.

There is no prettier or more

characteristic

picture of Japan than such a room, with gleaming black-bordered tatami

and a fine old hibachi,

at which a Japanese lady is sitting. Perhaps

the fire has become disarranged or burnt low, so with finished grace

she takes the hibashi

between her little taper fingers, deftly clips

the pieces of charcoal and piles them into a tiny pyramid. Around this

she draws the ash with the scraper until she has made a miniature

Fuji-san. She does not do this from any superstitious belief that the

nearer she approaches in her arrangement of the fire to the shape of

the sacred mountain the better it will burn—as I have somewhere

read—but because she knows the draught is better so, and to still

further aid combustion she burrows a little hole into the lip of the

tiny crater to admit the air. When my dainty lady has completed this to

her satisfaction she rests her pretty wrists against the edge of the

brazier, and holds her palms outstretched to warm them.

The hibachi

has several important appendages, chief of which is the

kettle used to heat the water for tea. These kettles are of every

conceivable shape and design, and of such beauty that the collector

burns with desire to add each fresh specimen he sees to his household

gods. They are made of silver, bronze, brass, shakudo, shibuichi, and

iron; but of them all the iron ones are the most fascinating. They are

very thick and heavy, often weighing four or five pounds—the philosophy

of this being that thick metal cools slowly. Some are round, some

square, some squat, and some tall, some are plain and some are

carved—and in the carving every whim

ever known to the Japanese artist is to be found. There are dragons,

flowers, landscapes, seascapes, gods, goddesses, animals, legends,

historical incidents, and geometrical designs depicted on them. One

never sees two alike. These kettles are called tetsu-bin, meaning

"iron bottle.''

The tetsu-bin

is placed over the hibachi

fire on a little contrivance consisting of a circular hoop of iron,

which lies buried in the ash. From this three little iron uprights

spring, when required, to support the kettle. This device is called the

san-toku,

or "three virtues"—the virtues desired in the fire being

that it may burn well, clearly, and hotly. Sometimes a wire screen is

placed on the san-toku, on which small cakes can be toasted. This is

called the ami,

or net; and in the case of the special screen, on

which the glutinous rice-bread, or mochi,

is baked, it is called

mochi-ami.

Around the hibachi circulates

not only the

domestic but also the social life of Japan. All warm themselves at it;

tea is brewed by means of it; guests are entertained, chess played,

and politics discussed beside it; secrets are told across it, and love

is made over it. The hibachi,

in fact, is accessory to so many of the

thoughts and sentiments of life in this land that it is easily the most

characteristic object of Japan.

It is quite astonishing

how quickly a cold room can be warmed by a hibachi well

supplied with

charcoal. The reason is that a charcoal fire gives out great heat, and

none of this heat is wasted; all the warmth generated by the fire is

disseminated into the room. There is no danger whatever of asphyxiation

when the better grades of charcoal are burnt; only the cheapest

varieties give off any poisonous fumes.

WRITING A LETTER

WRITING A LETTER

The hibachi,

however, is not

left in the room at night, for

any carbonic-acid fumes that may be freed naturally sink to the floor,

and Japanese people sleep but a few inches above the mats. It is

therefore removed and a small tabaco-bon

substituted for it. The

tabaco-bon

is a sine qua non,

for the tiny hibachi

that it contains

holds a choice piece of cherry charcoal which glows all night; whenever

a Japanese awakes, he or she must have a whiff or two from a pipe, as a

solace, before sleep comes again. The tabaco-bon is

therefore placed

close by the bedside.

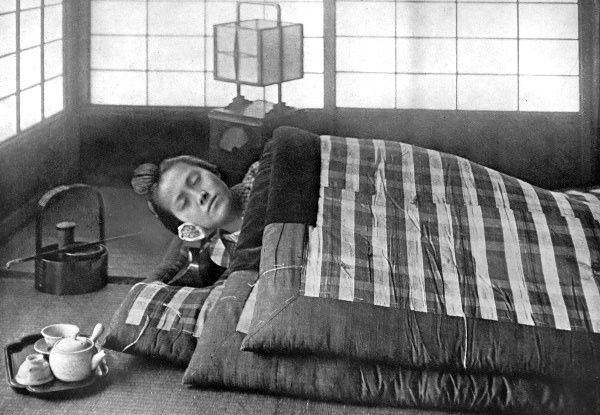

Beds are made of thick padded

quilts, called futon,

spread on the floor. There may be one or several

of them, and another is used as a covering. These futon are very

warm, and very much esteemed as safe and comfortable retreats by

Japanese fleas, which are the most robust and energetic of their kind.

The makura,

or pillow, used by men is a small round and rather hard

bolster. This makura

is very difficult for a foreigner to manage.

Though I have spent many months at Japanese inns, I have never mastered

the knack of keeping it from rolling off the futon and letting

my head

down with a bump. I invariably had to put my large camera-case at the

head of the bed to keep it in place—much to the amusement of every

neisan who

saw it there.

Women sleep on quite a

different pillow, and, as life at many country inns has few secrets,

such matters are open to the investigation of the curious. They use a

little lacquered stand with a soft pad on top which just fits the neck.

The head does not come into contact with this device at all. It

projects over it, so that the elaborate coiffure is not disarranged. In

the base of this pillow-stand there is a tiny drawer for the reception

of hair-pins and other such little feminine requisites.

"A delicate affair is beautiful hair" in most lands, but in Japan it

is a very serious matter. The dressing of a lady's

tresses may take an hour or more, and can only be done by a

professional kami-yui,

or coiffeuse,

who visits the house for this

purpose. When, therefore, the hair has been arranged, it is carefully

kept in order for several days, with merely a little prinking up each

morning. If, however, the hair be worn in the pretty foreign-style

modified pompadour, now affected by many Japanese girls, the services

of the coiffeuse

are, of course, not required.

Enormous

spiders, called kumo,

haunt Japanese houses. Their bodies are as large

as a filbert, and the legs fully four inches from tip to tip. They are

quite harmless, but have a distinctly unwelcome look as they walk

across the walls. One of the most Japanesey pictures I ever saw was a

pair of tiny youngsters, with arms round each other's necks, standing

in the passageway watching the peregrinations of a kumo which was

creeping on the other side of the semi-transparent shoji, its body

throwing a deep black shadow on the paper from the light of a lamp

burning in the room. Rats are a great nuisance in Japanese houses

because of the noise they make as they scamper over the thin resounding

boards comprising the ceiling. Though I have often been disturbed by

them, I have, however, never seen one in any native inn.

Walls have ears in Japanese rooms, and

even a sotto voce

conversation

held in an adjoining chamber can be heard. Not only have they ears, but

they have eyes as well, and it is quite a common occurrence to see a

human one peeping through some small hole in the shoji. Occasionally

you may detect a finger in the act of making such a hole, or enlarging

one already made. The paper, however, is fixed to the framework so

tightly that when a finger is poked through it, it makes a very audible

"pop"; so to obviate this the tip of the finger is moistened, and a

slight twisting motion enables the

hole to be made quite noiselessly. More than once I have apprehended

the little Paul Pry in the act, and caught the offending finger as it